My crime: Managing a media website!

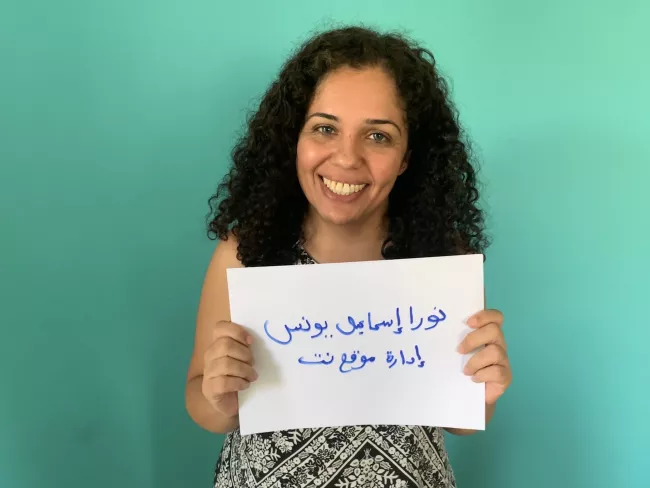

On June 24, 2020, security forces raided the offices of Al Manassa, leading to the arrest of our Editor-in-Chief, Nora Younis. Her detention, under charges of "managing a website without a license," "possessing software designed and developed without licenses from the Supreme Council for Media Regulation," and "infringing on the moral and financial rights of the copyright holder of an artistic work and wrongfully profiting," sent a chilling message to independent journalism in Egypt. She was the first Egyptian journalist to face charges under cybercrime law.

Despite Al Manassa's diligent efforts to obtain a license since 2018—efforts that were met with official silence—Younis' arrest and subsequent release on bail underscored the precarious environment in which Egyptian journalists operate.

Law is frequently wielded as a tool to stifle independent reporting. Today, the landscape remains profoundly challenging. Journalists, like Al Manassa's political cartoonist Ashraf Omar, continue to face arbitrary arrests, prolonged pretrial detentions, and charges such as "spreading false news" or "joining a terrorist group."

On the anniversary of that pivotal moment, Al Manassa is republishing Nora's testimony.

“There are four men here asking about you,” my colleague called to say as I was on my way to the office.

He sounded nervous, and was brief. I didn’t fail to notice the red microbus parked near the office with four similarly sized men in plain clothes standing nearby. We know from previous arrests that it always begins with a microbus and men in plain clothes.

I sent a quick message to our lawyer and shared with him the microbus’s license plate before going up to the office, feeling special because, unusually, they sent a red one for me.

I didn’t know at the time that they had literally stormed the office 45 minutes earlier. Two men had waited in front of the building to secure the entrance while six others went in. They roughed up my colleague, took his ID, and stopped him using his phone. They searched the office for back doors, and seemed surprised when he told them truthfully that no one else was there, although it was Covid-19 times and everyone was working from home.

They found two laptops that had not been used for a while, and two desktop computers that had never been used at all, cables and keyboards still wrapped and sealed.

When they didn’t find any staff on site, they shouted and threatened my colleague to reveal the address of “the other office where the rest of the staff must be hiding.” When he assured them that the office was actually closed “due to the coronavirus” and that no one except him and I came to the office, their boss went out to the balcony to make a few calls during which he briefed someone and consulted about next steps.

He then asked my colleague to call me without giving me any information. He asked two of his six men to go downstairs and hide in the street with the other two until I came upstairs.

Our office is located on a quiet street in Maadi, with balconies overlooking lemon, pear, mango, and orange trees. We chose this southern Cairo suburb for its quietness and the office’s proximity to a metro station. We also wanted to stay away from “hot spots.”

Newspapers and news websites are usually headquartered in Downtown or Dokki so that reporters can move quickly from their offices to sites of clashes or government offices, but that’s not the case anymore.

I entered the office to find four men in plain clothes. Two of them were smoking cigarettes inside our no-smoking office, while already inspecting the computers they found. I would find out later that one of them was an engineer with the rank of major who put together the technical report proving my crime a few hours later.

The older man introduced himself as the brigadier general heading the investigations department of the Central Authority for the Censorship of Works of Art (a body regulating intellectual property infringements). He showed me his ID and asked to enter my office. Had I known how much they mistreated my colleague at the time I wouldn’t have ordered them coffee.

The brigadier general asked when the company had been set up and for its licenses. Whenever he asked for a document, I pulled it out of a dossier we had put together in advance. All the documents he asked for were there in their entirety to the extent that he asked me if I had been expecting him.

The truth I didn’t tell him was that I had been expecting him for two years, if not more. When our website was blocked in 2017, I expected him. Whenever security forces stormed a news organization’s headquarters, I expected him. Whenever a journalist was stopped at the airport, I expected him. I was relieved when I weaned my daughter because that put me in a better position expecting him. Each time my son was done with school exams, I’d feel I was better prepared in expecting him.

It is because I expected this day for so long that we prepared well and obtained necessary licenses. My colleagues and I were keen on ensuring our company was fully legal, producing accurate content, and adhering to professional standards and the law more broadly.

I knew the brigadier general’s arrival was nearing when a bright, young researcher who collaborated with us was detained from his home a few weeks earlier. He disappeared for a few days before appearing at the prosecutor’s office, and during those days an entire interrogation session had been dedicated to questions about me and Al Manassa. I was following his writings well sourced social media posts four years earlier before inviting him to write for us; I saw a greater writer in his future.

This is what Al Manassa does: Identify young talents in the world of journalism and support them with skilled editing and a space to publish. This is my personal mission, too. I started my life as a blogger before I joined major news organizations inside and outside of Egypt.

As the managing editor of Al-Masry Al-Youm’s website, I gave the same space to young writers, whose articles soon garnered readership and admiration. They won awards year after year.

I have never understood why they questioned this young man about us. The last article he published on Al Manassa was in April 2019, and none of his articles were about Egypt. But who said there is logic behind what we are witnessing nowadays?

Wednesday, June 24 – Afternoon:

After three hours of interrogation disguised as chat, the nonsense started unfolding.

“This laptop has unlicensed software,” he said, “Adobe Illustrator and After Effects.”

To which I replied that the computer runs on Ubuntu, an open source operating system, so, it technically can’t run Adobe. So, it can’t have it.

“But I found Adobe software on it.”

“Can you show me?” I asked.

“I can’t,” he replied. “They’re there, but hidden. Prove to me they aren’t.”

I turned to the brigadier general and told him that this was unprofessional. “It’s not my job to find proof that the programs aren’t on the computer,” I said. “It’s your job to prove that they are. Anyway, we actually have two licenses to use Adobe, even with the absurdity of the allegation.”

“You’re right," he told me. “We’ll need to take the laptop and we’ll need you to come with us so that we can inspect it more closely.”

I felt a surge of fear and my hands trembled. We’d entered the depths of absurdity. Responding to stomach cramps I went into the bathroom and messaged our lawyer who was on his way to me:

“Am I getting arrested?”

“Yes,” he responded.

Suddenly, the fear evaporated, replaced by a kind of serenity. I breathed slowly and recalled everything I knew about arrest, interrogation, detention, and my rights as a defendant. "The anxiety of waiting is much worse than the disaster befalling" a proverb I strongly believe in. I prefer an official interrogation over a chat. I like clarity in roles and my adversaries showing their face, even if it means greater risk. I don’t do well in gray zones, even if I try.

I got into the red microbus with the brigadier general and his now seven men. He told me that we’re going to the headquarters of the Central Authority for the Censorship of Works of Art on Gameat Al-Dewal Al-Arabiya street in Mohandeseen. He tried to take my phone, but I insisted on calling my husband first. I quickly told him what had happened and where we were going, then I handed over my phone.

Instead of exiting toward the Corniche, the microbus headed to Maadi police station, driving through the quiet streets. As I looked out at the beautiful trees, I remembered the late Ahmed Seif El-Islam and decided that he would be my source of power in the coming hours and days—not as a lawyer, for I had never faced this situation before—but as a prisoner.

On a spring day in 2005, I met him for the first time as a journalist. In our first interview, he shared with me how he spent his jail time studying law. He came out of prison a human rights lawyer. I was deeply affected when he told me how he never dehumanized his jailers. He knew his jailers or torturers were but tools, who were not yet ready to realize the impact of their role on themselves before their victims.

Wednesday, June 24 – Evening:

After long hours of waiting without fidgeting in a windowless room alongside 22 stolen bikes guarded by two informants, the brigadier general asked me to sign the report he had written. I refused. I was taken down to the ground floor where they asked me if I had any cash or valuables on me. They had not told me anything and I didn’t ask, but I figured out handing over my personal effects means I was going into detention. I calmly handed them over and went in.

I knew that if I asked or requested anything, or even inquired about the time, they’d take joy in ignoring me, yelling at me, or even misleading me. I decided to disarm them by refraining from asking any questions. I knew that time was on my side; they’d have to bring me before a prosecutor, no matter how long it takes. I psychologically prepared for the worst, which helped me deal with everything that followed.

The women’s only cell in Maadi police station is 3.5 by 4.5 meters. This space includes a bathroom consisting of a toilet with an ever-dripping overhead shower right on top of it. A white curtain with Manhattan’s skyscrapers in gray and black separates the bathroom from the rest of the cell. In front of the bathroom lies a marble counter featuring a faucet without a sink or drain.

Food containers and bottles — both, empty and full — line up on the counter. Underneath it lies a big box for shoes and purses next to a large garbage bag. Across the wall, a clothesline runs the length of the room. It is always strung with clothes from end to end because all cellmates shower and wash and hang their clothes up to dry every day.

On the wall there’s a large AC that doesn’t work. Its grills are used to stack Styrofoam plates of cheese and processed cold cuts. Ten women occupy the rest of the space. I was the eleventh.

I approached them with a smile “I don’t want to bother anyone. Just tell me where to sit and what the rules are, and I’ll go along.” The cell boss was a confident woman in her 60s who cracked dry jokes without laughing and proudly described herself as “the owner of the capital’s biggest drug ring in Shaq El-Ta‘baan”, an area near Tora prison.

“What do you take us for? Come along honey, grab a bite. Sit wherever you want,” she said.

I ate with them as they introduced themselves and their charges: theft, drugs and prostitution. The one whom I later slept next to told me “I stole $120,000 and four diamond rings from a Christian guy. I thought there were only $4,000 and two rings in his safebox. When I opened it, I was stunned. But I didn’t get to enjoy it. The police identified me through the building’s CCTV and took everything back.”

They are all strong women who don’t claim innocence. They are at peace speaking about their crimes while briefly mentioning the poverty and destitution that led them here. Their biggest worry is the financial burden their families will bear to cover their expenses in prison.

They refuse to call the notorious women’s prison “Qanater”, as it is widely known. The one who would later sleep to my left said, “Qanater is the name of the place where we used to go out for picnics, ride a boat, eat feteer. It’s called the General Prison. Girls, no one’s to call it Qanater.”

I felt at ease among them because at least inside this cell, no one was claiming to be other than themselves. They asked me the questions with which they welcome any new inmate.

“What’s your charge?”, I told them “copyright infringement,” but they didn’t understand. “So, what do you do for a living?”

I said that I was a journalist, to which they responded “Oh, we just had another journalist here a month ago. She was recording an interview with a woman who’s been sitting in front of a prison because her son is locked up and they’re not giving her any letters from him.” They were talking about Lina Attalah and Laila Soueif.

On May 17, fellow journalist and chief editor of Mada Masr Lina Attalah was arrested in front of Tora Prison while interviewing Laila Soueif, mother of political prisoner Alaa Abdel Fattah. What were the chances that I would be locked in the same cell? How could these women still be here?

Surprisingly, some of my cellmates have spent over seven months in this can. Unlike prison, here they are not entitled to an “exercise hour,” time outside in the sun, or even a space to stretch.

When it was time to sleep, they gave me the third spot from the door. They chose it for me between two inmates who slept well on their sides and didn’t toss and fuss much in their sleep. We all had to sleep on our sides so that we’d all fit. But I couldn't sleep before 4 am. Every day, after they sweep and clean the cell, they stay up laughing and singing, and I wasn’t going to miss that.

Thursday, June 25 – Morning:

A police transport vehicle was jam-packed with 30 men cuffed together in twos behind a locked door. The remaining space where guards usually sit was less than a single square meter. Four of us, women, also cuffed together in twos, climbed up.

A policeman climbed up next to us and brought behind him two bikes — exhibits in a case of bike theft. Then, two other policemen climbed up; one of them was carrying my case exhibit: the laptop. The last door was then locked from the outside, leaving us, 4 women, 3 policemen, and 2 bikes on top of eachother.

I almost fell on a policeman who lit a cigarette inside this can of sardines. I asked him to “please” move his leg just a bit only to be met by him yelling, “You’re a defendant!”

He meant “you don’t get to ask for anything here.” I felt angry for a few moments, then I remembered how they want us to be angry or afraid. So I wasn’t bothered by the cuffs, having to stand for long hours, or their yelling. If we want to keep going, we must never let them get to us.

Many long hours passed as I waited at the prosecutor’s office, followed by an interrogation that lasted for an hour and a half. But this was all made easier when Al Manassa’s lawyer, Hassan Elazhary, told me that Al Manassa had remained in operation with its publishing unaffected, that lawyers had come outside to offer pro-bono legal support, that organizations had released statements, and there had been media coverage.

The prosecutor charged me with “creating an account on the information network with the aim of facilitating and committing a crime punishable by law; possessing software designed and developed without licenses from the National Telecom Regulatory Authority; infringing on the moral and financial rights of the copyright holder of an artistic work; and wrongfully profiting through the internet or an IT tool, the telecommunication service, and an audiovisual service.”

I answered all questions and submitted all the supporting documents, but the context of the interrogation didn’t offer me the chance to share the details.

In January 2016, we registered Al Manassa as a limited liability company with a capital of 2,000 Egyptian pounds (around $250 at the time). Colleagues and friends donated a printer, used desks and chairs, and some photos for the walls. A friend gifted us a fridge and an AC, another gifted us a whiteboard, and so on.

A while later we created the “deductions fund”, which is a fund that draws on salary deductions from tardy colleagues. We used the money to buy a coffee maker, then a PlayStation to pamper ourselves. When it was overflowing with cash, we bought a new set of chairs.

We were eager to start, but we still took the time and measures to stay on the right side of the law. We carefully studied publishing laws and before we launched we put together a style guide and a set of editorial principles. Two years later, we added the anti-harassment and anti-discrimination policies to ensure a safe working environment for everyone.

We registered our company’s website with the Information Technology Industry Development Agency in 2017. In 2018, the Supreme Council for Media Regulation/SCMR was formed with Makram Mohamed Ahmed as its head. He announced in October of the same year that websites needed to register to receive a license. The registration window was set to close just 14 calendar days from his announcement, and the requirements were crippling.

We raced time to complete the paperwork and pull together the 50,000 pounds (around $3,000) needed as registration fees. We raised the capital to 100,000 pounds as per requirements. We submitted the request by the deadline and awaited the license. Months passed without a response, so we sent two letters by registered mail to inquire about the status of our license.

We knocked on the council’s door several times and each time, we were told that a decision on us was yet to be reached. We kept working, since there is no legal provision in the media regulation law outlining the appropriate procedures should the council fail to respond.

Their silence was scary. We considered filing a case to compel a response, but then we thought the authorities might view this as an escalation, so we dropped the idea. We don’t want to incite hostility or anger. Ever since Al Manassa was born, our single objective was — and still is — to continue publishing with integrity and standards.

As for our equipment, all company-owned computers either run on licensed Windows or on Ubuntu, an open-source operating system (i.e. its copyright holders have waived all their moral and financial rights). The Windows computers have licensed Adobe software installed.

Since my personal computer is a Mac, we obtained an art production license from the Ministry of Culture, which cost us over 5,000 pounds (around $309), because we knew that the Central Authority for the Censorship of Works of Art would consider it an unlicensed video editing unit even if it didn’t have any video editing software.

Thursday, June 25 – Evening:

I returned to the police station with a smaller number of defendants and the two bikes. The inmate I was cuffed to didn’t stop crying; her detention was renewed for another 15 days and her lawyer didn’t show up. No one told me the prosecutor’s decision; they just said it hadn’t been issued yet. I returned to the cell and looked forward to getting some sleep.

I lowered my expectations deciding it’s always better to expect the worst. As I fell asleep, loud knocks banged the door. The women rose in fear, covered their hair and stood in two lines next to the walls bowing their heads.

How did this happen? How were all the detainees in a police station, not a prison, tamed into standing with their heads bowed as soon as they hear a knock just like the relationship between the dog and the bell in Pavlovian theory?

A man in plain clothes called my name and asked about my mother’s name. I knew that they would check the database for my name as a standard procedure to make sure I wasn’t wanted for any other cases before releasing me. That’s how I knew the prosecutor had decided to release me. I still didn't ask any questions. The man in plain clothes gave me a piece of paper and said, “Hold this.”

He suddenly took out a camera and tried to take a photo of me. I turned the page over to find my full name and the charges against me according to Maadi police station: Managing a website.

I refused to have my photo taken; I was afraid of finding myself on the Facebook page of the Ministry of Interior surrounded by weapons, drugs or cash, as often happens. But my cellmates shouted in one breath “Let them take your photo, it’s okay, we all did it.”

They took me to the second floor a bit later. Next to the stairs leading upward, there’s an always-dark, locked room. It bears a sign in big, golden letters: “Human Rights Office.” Upstairs, a detective sitting behind a desk took my hand and tried to sign a document with my fingerprint.

The document was titled “charges” in print and featured a lot of handwritten text. I pulled my hand back and asked to read it first before giving my fingerprint. He yelled, “Take her back.” I was returned to the cell.

Friday, June 26 – Daybreak:

I finally fell into deep sleep, but knocks on the door woke me. It was a second lieutenant who seemed new to the station. He cursed the inmates and asked each and every one of them “What’s your name and charge, girl?”

When it was the cell boss’s turn, she told him “I’m the station’s daughter, pasha. This chief and the one before him rose up the ranks on my watch, pasha. I hope one day to see you a chief.”

He yelled at me,“Pack your stuff and come with me.” I walked behind him, and he didn’t say a word. He handed me back my belongings and I stood there in complete silence until he broke it “What are you waiting for? Go home.”

At home, I realized how stupid I was. Why did I frown when they took my photo? This isn’t even a charge; journalism isn’t a crime. And what’s so problematic with “managing a website”? Maybe if I had smiled at the time and proudly held the piece of paper, they would have realized how absurd that charge is.

Dear reader,

We know very well that the overall environment in Egypt isn’t supportive of freedom of expression and journalism. We’ve seen a lot happen since we started. One by one, newspapers and websites shut down or were sold to bring changes to their editorial policies: Al-Tahrir, Al-Dostour, Al-Bedaiah, Al Badil, Manshoor and lately, Zahma and Mantiqti.

Day after day, the field grows empty around us. One by one, colleagues leave Egypt and go into exile. We know very well that in such circumstances, our survival depends on professionalism. My colleagues carefully check stories two or three times before publication, and we send dozens to our lawyer to review.

Why do we publish?

Do we enjoy the heartache? Isn’t it possible for everyone working at this website to find better positions abroad? No, we don’t enjoy the heartache. Yes, this team is excellent and could leave for better paying jobs. But continuing here, in this country, carries a different message.

One of the classic definitions of journalism is that it’s history’s first draft — I know this seems like an ideal, kitsch definition. But we want to continue publishing from a newsroom in the heart of Cairo, so that 20 years from now, a researcher or historian doesn’t have to ask if Egyptian journalism was swallowed by a black hole.

As one of very few news websites in Egypt, we tolerate such nonsense and the scary and ridiculous charges because we still believe that journalism has a role to play. We don’t accept that the only possible journalism about Egypt must come from outside Egypt.

The future of Al Manassa?

We will continue to publish in the same way, but we’ll be stricter in our standards so that the reports, investigations and stories the state confronts us with in the coming “raids” are stronger and greater in number.

Dear reader, we strive to remain here, operating from Egypt, with this quality or better. We strive to remain with you, and for that, we walk all possible paths.

(*) A version of this article first appeared in Arabic on June 28, 2020, while a version in English was kindly translated and published by Mada Masr on July 4, 2020, at a time when Al Manassa did not have an English Edition.

Published opinions reflect the views of its authors, not necessarily those of Al Manassa.