Egypt as the world’s grandmother: Alexandre Dumas’ forgotten voyage

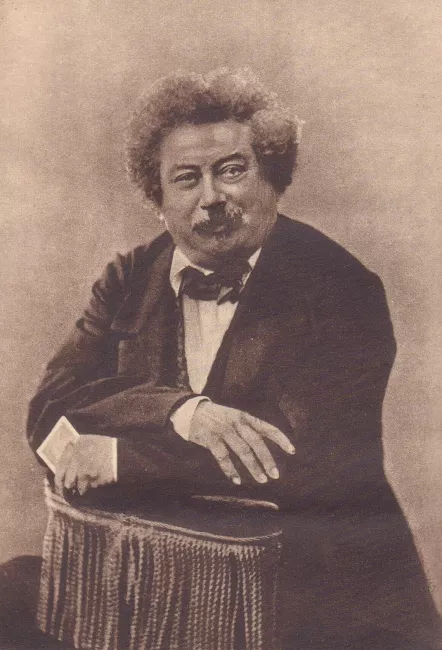

French novelist Alexandre Dumas (1802–1870) is best known for The Count of Monte Cristo (1844) and The Three Musketeers, published the same year to wide acclaim. Through these and countless other works, readers around the world came to know one of literature’s most prolific and imaginative storytellers.

Yet among his lesser-known writings lies an overlooked travelogue about Egypt—one that captures a pivotal moment in the country’s modern history, when Egypt stood at the threshold of change and the world’s fascination converged upon it.

Mohamed Ali rises to power

In 1805, Mohamed Ali Pasha consolidated his rule over Egypt, ushering in a rare period of stability that drew explorers, scholars, and travelers to its ancient landscape. Archaeological missions and tourist groups arrived in growing numbers, encouraged by the sweeping privileges the Pasha granted to foreigners.

Intent on securing European support for his vision of a modern Egyptian state, Mohamed Ali issued firmans and excavation permits that gave outsiders extraordinary freedom—to dig where they pleased and to keep what they unearthed.

Soon, the Nile Valley became a stage for imperial rivalry. British and French expeditions competed to claim the most dazzling relics and send them home to their national museums. Consular offices played a central role in this contest, with diplomats often leading excavations themselves or hosting visiting delegations eager for discovery.

Though Mohamed Ali offered equal privileges to both sides, his admiration for France was unmistakable. The French, for their part, seized every opportunity to carry away Egypt’s ancient treasures—fragments of a civilization that had long captured the Western imagination.

Friends in Alexandria

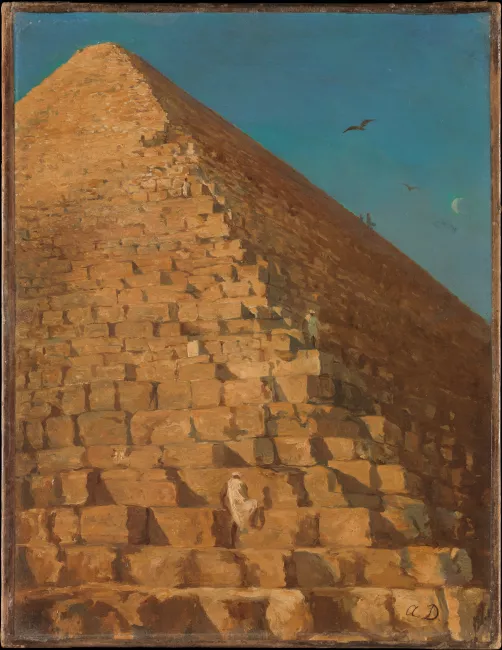

On April 22, 1830, a French mission arrived at the port of Alexandria led by Baron Taylor, a diplomat and theater director, accompanied by painter Adrien Dauzats, who frequently joined him on his journeys. The East served as a rich source of inspiration for many of Dauzats’ works.

While the delegation’s official purpose was to negotiate the transfer of two ancient obelisks to France, what distinguished this voyage was its connection to Alexandre Dumas.

Taylor, then the royal commissioner of the Comédie-Française, had first introduced Dumas to the Parisian stage through his play Henry III and His Court. Their collaboration soon deepened into friendship, and Taylor later introduced Dumas to Dauzats. The bond between writer and painter eventually produced Fifteen Days in Sinai (1839), part of Dumas’ "Impressions de Voyage" series—a literary account inspired by Taylor and Dauzats’ journey through Egypt.

This book remains largely unknown and appears to have received limited Arabic translation. But a quick read of the digital version available through France’s National Library—using smart translation tools—reveals an engaging narrative that documents life in 19th-century Egypt. The book is also available in a 19th-century English translation. Some passages veer into fiction, and modern readers should bear in mind the limitations of early translations, which occasionally distort nuance.

The world’s mysterious grandmother

Dumas’ fascination with Egypt was personal as well as literary. His father had served as a general in Napoleon Bonaparte’s army during the French invasion of 1798, and the son inherited his father’s sense of adventure.

Captivated by “the East and its enchantment,” Dumas opens Fifteen Days in Sinai by calling Egypt “the mysterious grandmother of the world”—a land that had passed down the enigma of its civilization, now scattered in ruins yet still alive in memory.

He writes that ancient Alexandria, once a beacon of knowledge and enlightenment, now lay buried beneath the mud-brick streets of the modern city, whose residents doused the ground with water several times a day to cool it in the summer heat.

Throughout the book, Dumas retains his trademark wit, finding humor in moments such as his first visit to Alexandria’s public baths or his clumsy attempts at camel riding. His lively, theatrical tone transforms every scene—from crossing the desert to scaling the pyramids—into both adventure and reflection, a dance between fascination and disbelief.

The present as a stage for the past

To Dumas, Egypt was a vast stage where fact, legend, and history performed together. Each stop on the travelers’ route becomes a gateway into another era—from the Exodus of the Israelites and the Crusaders’ landing at Damietta in 1249, to Napoleon’s 1798 campaign and the 1811 Citadel Massacre that cemented Mohamed Ali’s rule.

He threads these episodes together with ease and theatrical flair, linking history to the living streets of Cairo. Though proudly French, Dumas writes with surprising restraint when describing France’s military exploits, showing flashes of national pride only when recounting the Seventh Crusade, drawing heavily on "The Life of Saint Louis" by Jean de Joinville.

This balance of admiration and bias defines his portrayal of the East. He expresses genuine respect for its ancient depth while emphasizing its contrast to the West. At one point, he describes the Arab woman as “nothing but a slave... a prisoner; none but her master approaches her habitation. The greater her beauty, the greater her misery. Her life is suspended by a thread: if her veil rises, her head falls!”

Such passages reveal both the curiosity and condescension typical of European travelers of his time—an ambivalence that modern readers can now examine with critical distance.

Vivid observations

Between Alexandria, Damanhour, and Rosetta, Dumas—through his fictional narrators—records the pulse of Egyptian life. He notes the swarm of porters competing for passengers at the harbor, the bribe offered to pass a Turkish garrison without stamped papers, and the sight of a naked man revered on the steps of a mosque.

In Dumas’ depiction, Cairo is divided into four quarters resembling medieval European cities: Arab, Greek, Jewish, and Christian. The difference, however, is that each district was enclosed by gates guarded by soldiers at night.

Naturally, the French delegation stayed in the Christian quarter, known as the “Frankish quarter,” where residents were discouraged from wearing European clothing outside its bounds for their own safety.

At the time, Cairo’s population hovered around 300,000. Its narrow alleys teemed with life, its markets organized by trade: textiles in one, food in another, and in a grim reflection of the era, a women’s market where enslaved women were displayed by color, nationality, and age.

The road of bones

One of the most harrowing scenes in Dumas’ book involves pilgrims collapsing from heat and exhaustion en route to the holy lands, their corpses and the remains of their camels gradually turning into skeletons scattered across the desert. These bones, he writes, lined the paths to Sinai and served as markers for travelers heading toward the peninsula.

But the bones of pilgrims were not the only ones buried beneath Egypt’s sands. The remains of enslaved people—captured in raids and herded north from Sudan to Cairo—formed another grim layer of the country’s history.

Every three or four years, Mohamed Ali dispatched expeditions to abduct enslaved men and women from Darfur and Kordofan. These missions captured as many tribal members as they could, graded them, and forced them into caravans to Egypt. Along the way, the ill and weak succumbed to exhaustion and were devoured by wolves. Those who survived—masters and captives alike—endured the brutal desert heat and deadly sandstorms, often arriving in Cairo with a third or even half their numbers lost.

As Dumas recounts these tragedies, his narrative shifts back to the journey itself: the travelers pressing onward to the fortified monastery of Saint Catherine, climbing Mount Sinai, and wandering through its chapels and hermit cells before sailing north again through Damietta, Jaffa, and Jerusalem.

The expedition left behind not only Dumas’ literary impressions but also a rich portfolio of paintings by Adrien Dauzats, capturing Egypt’s landscapes and daily life in luminous color and detail.

A journey never realized

In his final years, Dumas’ popularity in Paris waned, and he faced mounting financial troubles. Political upheaval in France halted the serialization of his novels, and his private theater, the Théâtre Historique, suffered heavy losses and eventually shut down. Yet his appetite for adventure never dimmed.

In 1860, Dumas planned a Mediterranean tour that would include Egypt, Sparta, Athens, Corinth, ancient Troy, Abydos, and Constantinople. But he abandoned the trip at the last minute.

Thus, “Fifteen Days in Sinai” remains his only encounter, real or imagined, with the land of the pharaohs: a literary pilgrimage through the Egypt of memory and myth, where the past never truly recedes, and where every ruin whispers the story of civilization’s “mysterious grandmother.”

Thus, “Fifteen Days in Sinai” remains his only imagined encounter with the land of the pharaohs—a literary journey through the noisy, captivating land that had held the world's attention for decades.