The 1952 Cairo Fire: What burned, and who lit the match?

It is often said that history is written by the victors. But what if some chapters of “history” were defeats for everyone? Then the central task becomes forgetting what cannot be fully forgotten, because its weight still presses on those who lived through it.

Some events remain collective defeats—a shared shame casting a long shadow over the present. When the past refuses to confront its own disgrace, denial becomes a self-reproducing loop. What remains are flimsy, incoherent, and often absurd popular narratives. In Egypt, parts of our modern history are, quite literally, a history of denial.

Walk today through Cairo’s old working-class neighborhoods and you’ll find alleyways renamed for martyrs killed on Friday, Jan. 28, 2011. Sometimes their faces still hang at the entrances. At the same time, official media pushes a narrative that treats the January uprising as a conspiracy, insisting that those who stormed and burned police stations that night were infiltrators from Hamas and Hezbollah, plus Muslim Brotherhood operatives—not furious residents of popular districts.

Even the most pessimistic observer would hesitate to believe this erasure can succeed in an age of daily, living, mass documentation—on paper and digitally in audio and video. And yet a little skepticism is healthy. Great moments of mass revolt have often been downgraded into “unfortunate events,” or remade into conspiracies whose authorship is traded among political actors. One such moment—no less central—is the Cairo Fire of Jan. 26, 1952.

Denial is not just a river in Egypt

The way the Cairo Fire has been remembered—and misremembered—has long filled me with unease. It is a case study in what might be called the modern Egyptian disease of denial when confronted with seismic moments and decisive turns.

How the event was handled by Egypt’s “national forces” also tells us something about what may happen to the history of January 2011. I owe much of my own understanding of the Cairo Fire to what I witnessed and learned in 2011; without those experiences, I might have remained trapped in the same contradictory, distorted narratives that still circulate about 1952.

More than 65 years later, responsibility for the fire still lacks a settled account. Instead, we have rival versions of comparable weight, rising and falling with political circumstance. All of them are partial. All of them conceal more than they reveal. Everyone accuses everyone else: King Farouk; Misr Al-Fatah; the Muslim Brotherhood; sometimes even the Free Officers. British intelligence appears in most versions as a key actor.

The mutual accusations persist because no one wants to return to what came before the fire: the context, the prevailing rhetoric, the political tactics that pushed the country toward explosion. Above all, no one wants to name the elephant in the room: Cairo’s poor—who supplied the fuel, the bodies, and the force of the event.

Before the uprising

The Cairo Fire of 1952 was the dramatic culmination of six years of turbulent political and social mobilization worldwide. Egypt was not an exception. World War II ended in 1945, opening a period of global upheaval as states and societies struggled to shape the postwar order amid collapsing empires and rising powers.

Egypt moved early. In January 1946, a wave of student and worker strikes erupted and set the tone of politics until July 1952. A visibly left-leaning mood rose within the student-labor movement, placing social reform at the heart of national discourse for the first time. The movement was radical enough to chant for the fall of King Farouk, to brand his rule tyrannical, and to clash with British forces in Cairo. Many were killed and wounded. A general strike was declared on March 8, 1946.

Workers and students unite

The worker and student movement of early 1946 signaled that serious political and social change could no longer be postponed. Then came May 1948—the creation of Israel and Farouk’s attempt to redirect mass anger toward the war in Palestine. The defeat of the Egyptian and Arab armies by a nascent Zionist force added two items to the national agenda: the “Zionist question” and the condition of Egypt’s armed forces.

Political struggle intensified. Its language sharpened. Physical liquidation and assassination entered the toolbox. Prime Minister Ahmad Maher was assassinated. The Muslim Brotherhood assassinated Prime Minister Mahmoud Fahmi El-Nokrashy after he dissolved the group; the Saadists retaliated by assassinating Hassan Al-Banna the following year. In the same period, Amin Osman—a Wafd figure—was assassinated, and an attempt was made on Mustafa Al-Nahhas. Anwar Sadat played a central role in both operations.

The years 1946 to 1952 carried a rapidly escalating radical mood—in action and in thought. Full independence seemed inevitable. What remained unclear was its pace and the political order that would follow. Traditional forces—the Palace and the Wafd alike—lost authority. New forces born of a rising middle class gained weight: the Muslim Brotherhood, communists and Misr Al-Fatah. Even the Wafd developed a more left-leaning current among younger members, known as the Wafdist Vanguard, more aligned with the left and more critical of the pasha class that dominated the party.

All this unfolded amid major global shifts: the United States rising to hegemony, followed by the Soviet Union, and the decline of old British and French colonialism. Most Egyptian political forces did not read these changes with enough acuity—perhaps with one exception: a young officer named Gamal Abdel Nasser, who built a progressive national organization inside the armed forces, destined to outgrow—and ultimately overshadow—the rest and have the decisive word at the end of the 1946–1952 cycle.

The political conditions of the uprising

Farouk understood his legitimacy was eroding. Scandals at Abdeen Palace, the flight of Queen Nazli and Princess Fawzia abroad, and their conversion to Christianity chipped away at the monarchy’s aura. Farouk—who joked that soon only the King of Britain and the four kings in a pack of cards would remain—chose accommodation. He struck a historic bargain with the Wafd and allowed genuinely free parliamentary elections in early 1950.

The Wafd of course won, but not with its former dominance, gaining only 69% of the seats. It was evidence that the party’s dominance of the national movement had faded and that new actors had entered parliament.

Mustafa Al-Nahhas absorbed these changes with the mindset of two decades earlier. In November 1951, he announced the unilateral abrogation of the 1936 treaty, declaring to parliament: “For Egypt I signed the 1936 treaty, and for Egypt I ask you today to annul it.”

Nahhas escalated the national battle against the British without offering urgent social reforms to meet the needs of a suffering population. He invested in rhetorical escalation against the British and foreigners—whether as strategy or as a way to evade the social demands of the moment. The result was predictable: the street was repoliticized through more radical nationalist language, but without the social content the situation required. The explosion came—and it hit everyone.

Declaring “jihad”

Annulment of the treaty amounted to a declaration that Britain’s presence in the Canal Zone was illegitimate—and that armed resistance was legitimate.

Within weeks, almost every political force declared “jihad” and rushed to send fedayeen to the Canal, whether or not the effort was serious or coherent. The Muslim Brotherhood, communists, Misr Al-Fatah, the National Party, groups of young officers and enthusiastic students began recruitment and training.

It did not stop there. Gangs of thieves and thugs announced the same intention. Some even went, looting British camps along the way.

Before long, the spread of weapons was slipping out of control. National fervor surged, and everyone was looking for arms to join the battle. The Wafd government moved to contain the process, placing fedayeen work under Interior Ministry supervision led by Fouad Serageddin. In a development both farcical and historic, the Egyptian police—long among the closest internal partners of the British—became the field commanders of armed operations against them.

The Wafd had not thought through the consequences of its decision. Preserving public order and the state’s monopoly over arms became paramount, dragging the police into an unprecedented, poorly calculated confrontation with Britain. Less than two months later, it would culminate in one of the most absurd scenes in modern Egyptian history: police and people united against the British. Then the city burned.

The day of the fire: who burned, and who was burned?

Nothing about that day came out of nowhere. Egyptians spent hours following news of clashes between British forces and Egyptian police around the Ismailia governorate building on Jan. 25. Egyptian radio broadcast Quranic verses continuously. The atmosphere was charged. A propaganda war between Egypt and Britain had escalated for weeks. Britain declared its intention to crush fedayeen attacks in the Canal, which were now shielded by Egyptian police.

The assault on the Ismailia governorate building was part of a pre-planned operation to arrest the fedayeen sheltering inside. The decisive escalation came when the Egyptian government refused to yield. Serageddin ordered the police to fight to the last bullet, and they did. After a full day of combat, 150 Egyptians were killed and nearly 1,000 captured. Thirty British soldiers were killed or wounded. The tragedy is remembered every year on Police Day (Jan. 25).

Against the rich and foreigners

“Tarek,” a participant, recalled being a first-year secondary student who joined demonstrations the morning of Jan. 26, 1952. “Our anger was overwhelming,” he said. “By midday I saw shops burning downtown. I had to go home when we heard the army was coming.”

Another participant, a building doorman who asked not to be named, put it bluntly: “I went to burn the big shots and the foreigners.” Few lines capture the moment more precisely. What unfolded was both a national and a class uprising: hatred of foreigners fused with resentment of local elites. The targets were where the rich gathered, shopped, and worked.

The late historian Salah Issa described witnessing the burning of Badia’s Casino in Opera Square: a protest turned into verbal confrontation with patrons, then violence and fire that consumed the casino and the building.

Norman Getsinger, an American intelligence liaison at the Cairo embassy from 1951 to 1953, later described the day in an interview with a US diplomatic studies body in 2000. Shepheard’s Hotel, he said, was destroyed. “Mobs were led through the streets by trucks” carrying gasoline. Buildings later burned had been marked with an X the day before—many of them clubs frequented by British and foreigners.

“This was the day when the British were coming out of their club, I think it is called the Jockey’s Club, and thrown back into the burning building by the mob. There were a number of Brits burned alive,” he recalled.

He described embassy staff evacuations, the burning of secret materials and crowds attempting to climb embassy walls until Egyptian army units arrived, and “we were saved.”

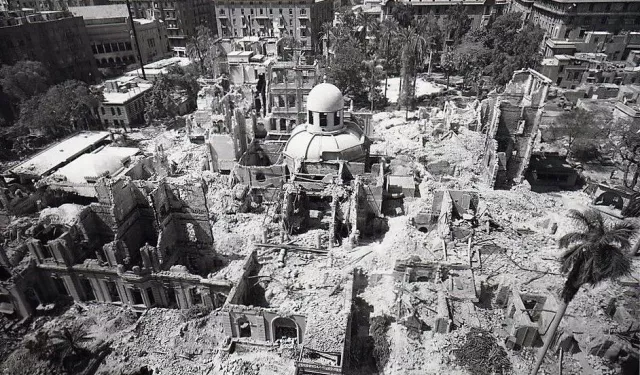

The Cairo Fire—also known as Black Saturday—killed between 26 and 46 people, depending on the account. The scale of destruction was staggering: 700 establishments were set on fire across downtown Cairo, including 13 major hotels, 40 cinemas, 73 cafés and restaurants, 92 bars and 16 clubs.

In plain terms, what burned was the jewel of Cairo’s modern urban core—the meeting place and commercial world of local and foreign bourgeois elites. The “refined world” went up in flames within sight of Abdeen Palace, where Farouk’s throne sat.

Did the British burn themselves?

The late Saad Zaghloul Fouad, a nationalist fedayee, argued that British intelligence involvement was beyond doubt and that trained thugs linked to British intelligence in the Canal lit the fires. The communist thinker—and my late grandfather—Saad Zahran offered a similar view, noting that many of the targeted sites were exclusive foreign venues unknown to residents of poor neighborhoods. Both, strikingly, dismissed the possibility that enraged police enabled the crowds, or that palace servants and guards played a role—and both also noted how illogical it would be for the British to burn themselves alive.

The French historian Anne-Claire Kerboeuf, in “Re-envisioning Egypt 1919–1952,” wrote that police anger was driven not only by the Ismailia battle but by their own labor demands, including wage disputes. She noted that a strike had been planned that same day among workers at Cairo Airport and that police detained four British planes until the Egyptian army intervened. Kerboeuf also wrote that hundreds of police joined demonstrations from Cairo University and Al-Azhar Mosque, and that throughout the long day the police either participated in burning the city or, at minimum, looked away.

She added that one forgotten incident on that strange day was student demonstrations gathering outside parliament. The Wafd minister Abdel Fattah Hassan Pasha addressed the crowds, praised their patriotism, vowed revenge for Egyptian blood, and went so far as to say the Wafd government would cut relations with Britain and strengthen ties with the Soviet Union.

The Cairo Fire, like many urban uprisings driven by the poor, was terrifying to witness from the position of spectator. The farcical tragedy is that to this day, every actor is accused of burning Cairo—except those who actually burned it: residents of poor neighborhoods, aided by the complicity, and sometimes direct support, of an Egyptian police force enraged by what had happened to its men in Ismailia the night before. For Egypt’s elites, the Cairo Fire was a shock whose effects never fully ended, because it was the first “revolt of the hungry” in modern Cairo—under the escort and protection of the police. It was a double nightmare.

What did history burn?

What burned first was not Cairo, but the world that dominated it: the Wafd’s world and the old national movement. Its historic leadership belonged to reactionary social forces, less because of ideological blindness than because of their class composition: a landed bourgeoisie. They failed to see that equitable social reform was the condition of their own survival. Their world, with its internal conflicts, its silent bargains, and its positioning vis-à-vis the British, collapsed swiftly and dramatically.

The Egyptian police, which until recently had been a pillar of British rule, clashed with the British to the point of armed combat and helped ignite the heart of Cairo. Few people remember that a British general, Thomas Russell Pasha, ran Egypt’s public security and served as Cairo’s security chief for more than a quarter-century, until 1947.

The police’s clash with Britain—and the burning of downtown Cairo—signaled the definitive end of the world of the Palace, the Wafd, and the British. It also prepared the ground for the ascent of the army and its political organizations.

Published opinions reflect the views of its authors, not necessarily those of Al Manassa.