How the West dances around Gaza

A few days ago, in a cavernous hall in Madrid, an event described as an “artistic celebration” was staged to mark the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People. The word celebration sat awkwardly with the date itself. The 29th of November, marking the anniversary of UN Resolution 181 which created the plan for the partition of Palestine.

This was not a day chosen for joy but for grief. It marked the opening chapter of the Nakba, the catastrophe that tore a people from their land. To celebrate such a moment is to confuse mourning with merriment.

The evening opened with a young actress delivering a theatrical introduction. Before her sat a familiar constellation: the Palestinian ambassador, activists, artists, intellectuals. With solemn enthusiasm, she read a prepared text introducing a Palestinian-Spanish youth dabke troupe.

She explained dabke’s place in Palestinian culture and urged the audience to watch the performance with the reverence it deserved. Then, striving for something like myth, she announced—without a hint of irony—that children in Gaza dance dabke even as bombs fall around them.

No one dared interrupt. No one gently pulled her back from the impossibility she was trying to describe. In Gaza, where bombardment has scarcely paused for nearly two years, children do not dance. Nor do adults. They run, they hide, they search for the living, or they die.

The romance of jungle resistance

Her words summoned an older image lodged deep in the Western imagination. Cubans dancing salsa while firing rifles in the heat of revolutionary struggle. From the late 1950s onward, this fantasy took hold, spawning a genre that fused dance and resistance, aesthetic pleasure and armed sacrifice. In this telling, the revolution advanced through the jungle to a rhythm section; bullets flying, hips swaying, joy intact.

It is a beautiful fiction, unsupported by a single document or credible eyewitness account. There are no records of Cuban guerrillas dancing in the Sierra Maestra on the eve of Batista's demise in Jan. 1, 1959, nor during the Bay of Pigs, nor as they face decades of US hostility. Combat and dance do not coexist. A body braced to survive—aiming, crouching, listening—cannot abandon itself to rhythm. When a comrade collapses beside you in a trench or behind a shattered wall, the instinct is not movement but mourning.

What was offered in Madrid went further still. The dancers were no longer armed adults but children; the setting no longer a jungle but the pulverized ruins of Gaza. A dance, we were told, amid the rubble. This was not resistance but hallucination, an aesthetic severed from reality.

A grotesque fantasy amid extermination

In the Levant, dabke is a social dance. It belongs to weddings, festivals, moments of shared happiness. It is not a dance of mourning. In Palestine, however, it has taken on an added meaning. Like the keffiyeh, the embroidered thobe and the Arabic language itself, dabke has become a declaration of existence in the face of erasure. Israel has long sought to appropriate elements of Palestinian culture, fashioning a national identity from what it has looted. In this context, dabke says: we are here, we have roots, we are not ghosts.

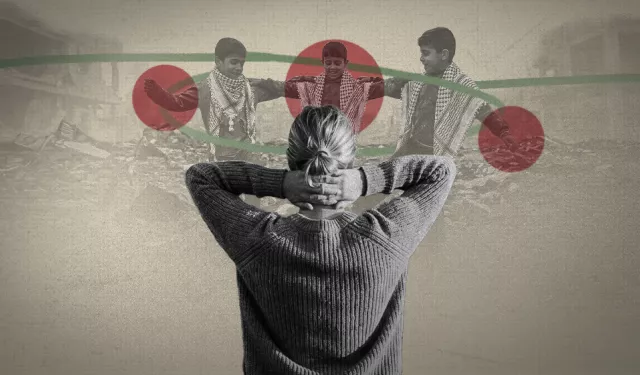

But to imagine children dancing dabke while their homes collapse and their families are buried is to push symbolism into farce. This image comforts the spectator, not the besieged. Death becomes a stage; the victims perform for distant sympathizers.

Mythical invincibility

Why does this persist? Why is there such insistence—among Western liberals and sections of the Arab diaspora—on seeing Palestinians not as victims of a ferocious colonial project but as mythic beings, eternally unbroken, forever dancing?

The myth is old. Yasser Arafat once spoke of Palestinians as “a people of giants”, too heroic to be defeated. The idea survived him: a nation composed entirely of heroes, stretching from the occupied territories to the camps and the diaspora. It is not a liberating image. It is a burden.

To insist on permanent heroism is to deny the right to collapse, to grieve, to despair. It strips people of their humanity and recasts them as characters in a political fable. Now the myth demands a new emblem: the child who dances dabke beneath falling bombs. The distortion is threefold. A celebratory dance is elevated into sacred defiance; Palestinians are rendered superhuman, untouched even by genocide; and mass extermination is aestheticized as resilience. The child does not scream, bleed or die. She dances.

It is a lie made seductive because it dulls the horror.

The violence of Western romanticism

These fantasies are not born in Gaza. They are manufactured in Europe and North America, where solidarity is often entangled with narcissism. In the early weeks of the current genocide, Western artists flooded social media with images of Palestinian couples dancing. Dressed not in recognizable Palestinian clothes, but in vaguely “indigenous” costumes borrowed from Latin America and recolored in the hues of the Palestinian flag. The intention may have been solidarity, but the result was abstraction. These were not Palestinians; they were a generic noble victim, repackaged for Instagram.

For Palestinians, such imagery is not flattering. To be likened to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas is not homage but prophecy: extinction, museums, reservations, footnotes. The dance of resistance becomes a rehearsal for disappearance, a eulogy written too early.

A hero's dance under a buzzing sky

These myths intensify at moments of absolute defeat. When entire neighborhoods are erased and children die in their hundreds, we reach for beauty to soften the blow. We dress the dead child in folklore. We insist she danced.

But these stories serve the storyteller, not the dead. The child needed food, shelter, a ceasefire. She needed to live. She did not need to become a symbol.

This is how genocide is made bearable: not by denial, but by choreography. Not by erasing death, but by turning it into spectacle. Better, perhaps, to let her be only what she was—a victim. Better to honor her pain than to embellish it.

It's curtains

When the evening ended, I considered approaching the actress who had read the opening lines. I wanted to ask who wrote that script, and whether she truly believed that a starving child beneath rubble could dance. I wanted to tell her that Cuba no longer dances as it once did. Its professional dancers have left. The so-called people of giants have scattered under economic collapse, blackouts, and despair. They are no longer dancing revolutionaries. They are migrants.

I said nothing. I stepped instead into the cold Madrid night, holding one hope, thin and stubborn: that when this extermination ends—if it ends—there will still be someone left in Gaza who can dance.

Published opinions reflect the views of its authors, not necessarily those of Al Manassa.

The return of the baltagiya?

30-6-2025

Will Israel end the same way as Apartheid?

7-10-2025

Gaza’s gamble: The price of making the world watch

7-10-2025

To Palestine| Sailing through fear, carried by hope

27-9-2025

To Palestine| From Bahrain to Gaza carrying a father’s legacy

24-9-2025

To Palestine| From boats of death to boats against death

23-9-2025