The economy of loneliness

Our emotions as a business model

On March 15, 2020, just before the official COVID-19 lockdown and curfew, my phone buzzed nonstop with Facebook notifications of planned events' cancellations. The same day, the government suspended schools for two weeks and banned all public gatherings in an effort to contain the virus.

What followed was one of the most surreal periods of my life.

Social distancing and isolation were not mandatory, but rather personal choices based on individual conviction and capacity. There was no real pressure from society or state. Cafes closed, but gatherings didn’t stop; they just moved indoors where friends continued to meet and party at home with only token efforts to keep their distance. Of course, every infection was blamed on delivery services, never on the get-togethers.

It was easy to feel morally superior and judge others for their recklessness. However, that image cracked when a close friend jokingly accused me of having benefited from the pandemic—or even conspired to cause it—just so I could justify my long spells of solitude without guilt.

Across the Mediterranean, European countries imposed stricter lockdowns, which may have helped limit the virus’s spread. However, the psychological toll there seemed heavier.

I’m no psychologist, but when I later visited some European cities, I saw the emotional scars on friends who had endured extreme isolation. They struggled with social interactions and showed a concerning increase in drug use.

Loneliness didn’t start with the pandemic

The pandemic wasn’t the beginning of the loneliness crisis. It was just the moment I first came to fully grasp that human beings need one another as much as they need air.

I can’t hide my skepticism whenever I hear a white man complaining about loneliness. The first time I read about America’s loneliness epidemic, my gut reaction was predictable. According to a survey by the American Psychological Association, about one-third of Americans feel lonely. A Gallup report, in collaboration with Meta, found that nearly a quarter of the global population (excluding China) suffers from intense loneliness.

But what do we even mean by loneliness? Are its causes universal across cultures?

If we ask a group of people whether they feel lonely, will we get consistent answers? What triggers this feeling? Is it the absence of a nuclear family?

For someone like me, who doesn’t idealize the traditional family model, my definition of loneliness will differ from someone who dreams of building their own family.

Is it the loss of friends who emigrated? Or is it the absence of the public sphere and lack of community? Do parents feel lonely when their children move out? Do those children feel lonely a few years later when living independently? What about someone with social anxiety who avoids public gatherings—do they feel lonely, or is their solitude a sanctuary rather than a void?

Perhaps each of us has their own unique shade of loneliness.

Blame it on the tech

Blaming technology and social media for every new social phenomenon or mental health issue has become the go-to tactic. These platforms may share some of the blame, especially for younger age groups still developing emotional maturity. Personally, I believe children shouldn’t be allowed on social media before age 16.

Still, that doesn’t mean tech alone is at fault—especially for millennials, a generation born amid the rubble of failed revolutions and aborted reform.

Is it fair to blame technology for the collapse of office life and the rise of isolation, when the real causes are economic pressures that force millions to work from home to save on commuting costs, especially in countries where gas prices can quadruple in a year?

Technology isn’t off the hook. Every new tech shift comes with its demons. But reducing the issue to a single narrative only deepens our ignorance rather than explaining reality.

Monetizing loneliness

A few weeks ago, I tried a social networking app that connects five strangers for dinner to foster new friendships. The service is relatively cheap, and like most things in Egypt, it’s easy to find people using such platforms for romantic pursuits.

I wasn’t searching; I was just bored. And honestly, I went in biased and came out feeling even more lonely and disconnected from my community. The conversations about relationships, economics, and gender were not just off-putting—they made me nauseous.

Before the dinner ended, I bet myself that someone would suggest selling the Suez Canal in Egyptian pounds to fix the economy. Thankfully, I lost that bet.

In recent years, the explosion of friendship and dating apps has transformed the sector into a multi-billion dollar industry, with Match Group alone generating $4 billion annually from subscriptions.

These apps profit by “setting a price for ending loneliness.” Men pay for more visibility; women pay for more safety. No one at these companies wants you to find what you’re looking for too quickly. The goal is to keep you engaged, searching and paying for as long as possible.

It’s no surprise, then, that people often feel even more alone after using these apps.

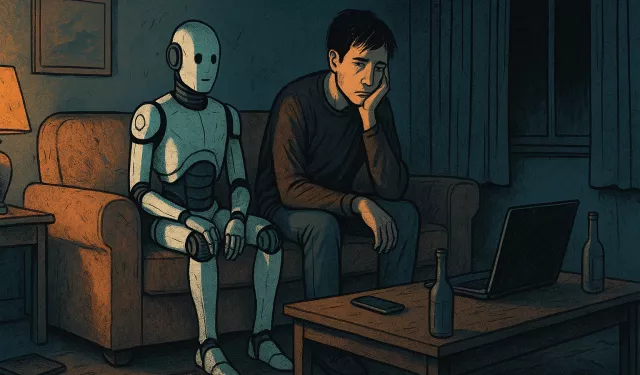

Now, the global village idiot Mark Zuckerberg has a new solution to loneliness: robots. Yes, we are in the age of AI.

In a recent interview, Zuckerberg said chatbots are our last hope. I will try to be polite in responding to that statement.

Zuckerberg admits that robots aren’t the ideal solution, but rather, what we have available. Other companies are heading down the same path—robot friends, robot therapists, digital girlfriends, even virtual moms.

The idea of losing my father terrifies me, but replacing him with a robot that mimics his voice, facial expressions, and the glimmer in his eye as he tells a story for the first time? That’s something I can’t stomach.

Yes, the acceleration of social deterioration can be linked to the speed of capitalism itself, to what Karl Marx called “alienation.” But allow me a moment outside Marxism; we’re not trying to dismantle the system—we’re just trying to survive it.

Still, how can we ignore this blatant profiteering off people’s yearning for real connection? Are we going to let US tech companies deepen our isolation, only to sell us a digital companion someday on an open marketplace and for a monthly fee?

(*) A version of this article first appeared in Arabic on June 3, 2025.