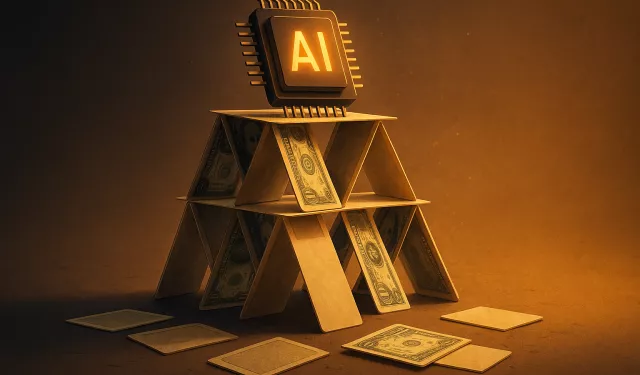

Not everybody is ready for the fall of the AI house of cards

Between the winter of 2022 and the summer of 2023, the global tech industry experienced successive waves of layoffs across technical sectors. Major technology companies dismissed tens of thousands of workers, and soon, others around the world followed suit under the pretext of “cutting costs.”

While panic spread within the sector, others welcomed it. I was one of them. This wasn’t out of malice towards laid-off workers, but rather because it signaled the possible decline of the hypergrowth strategy that had governed how companies and products were built for years.

Burn rate capitalism

The hypergrowth strategy results in massive financial costs and negligible profits. It is based on the principle of expanding rapidly at any cost and dominating the largest possible market share, regardless of financial losses.

If a developer quits and there’s concern about project delays, the company hires three others as a safeguard. If a competitor offers the same product, prices are slashed—sometimes by half—just to acquire more users.

But in the end, this strategy leads to a bloated bill and minuscule profits. One need not study economics or business to know that when expenses surpass revenues, a project is on the path to collapse, unless someone covers the losses. This is where venture capital/VC steps in, playing the role of funder to plug the gap.

VCs are willing to absorb losses if they believe in the founding team’s potential to keep pushing forwards. At that point, the company expands aggressively, competes for users, and lures talent away from competitors. Based on inflated numbers, founders offer projections of future profits.

The mirage of public offerings

This story usually ends in one of two ways: either the company miraculously balances revenue and expenses—rarely the case—or it goes public, allowing the VCs to cash out with profit.

And so, houses of cards were built, entirely dependent on funding, with little thought given to generating actual profit. Large teams produced very little, and multimillion-dollar funding rounds were exchanged for minor stakes in companies, all hinging on an uncertain future.

But after the first shockwaves in the post-pandemic financial markets, coupled with rising interest rates in the USA, companies were forced to re-evaluate, cutting costs and chasing profitability.

When the correction came in the form of mass layoffs, many of us saw a glimmer of hope. The unsustainable model for building companies appeared to be fading. VCs shifted their rhetoric, now emphasizing profitability over growth-at-any-cost.

A new house of cards, with a higher price

No sooner had the dust settled than a new house of cards emerged—larger, shinier, but even more fragile: generative AI. Companies like OpenAI and Midjourney have become living embodiments of the hypergrowth model, but on a scale we’ve never seen before.

What makes this round of hypergrowth different is that the losses are not limited to inflated payrolls or excessive marketing budgets. A new and far more burdensome line item has appeared: the operating cost of every user request. Each query posed to ChatGPT or image generated via DALL·E translates directly into tangible costs—consumed energy and processing time on expensive chips.

We are now in the honeymoon phase of AI, where VC covers this massive bill. While users pay symbolic subscription fees, companies are absorbing costs that can run into hundreds of dollars per active user.

This unsustainable reality replicates the same old formula: capture the largest number of users, collect their data, get them dependent—and wait for the reckoning.

As expected, founders deflect when asked about actual costs or long-term viability. When a Senate committee asked Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI and one of the key figures in this new wave, about the energy costs of running AI data centers, his response drifted into philosophical speculation about nuclear fusion as a limitless, eco-friendly power source, as if that dream were within easy reach. It ignored the geopolitical reality of energy markets—markets that have sparked wars, toppled regimes, and built empires.

When the real bill arrives

In that inevitable moment of reckoning, when investor capital dries up, these companies will be forced to lay out a clear path to profitability. This will fundamentally change our relationship with AI tools.

Those relatively cheap, unlimited-use subscriptions will disappear. Services will be priced based on actual consumption—like electricity or mobile data. Users will start thinking twice before asking AI to draft a simple message or generate a throwaway image, because every request will have a tangible cost.

Generative AI will shift from an accessible curiosity to a high-cost productivity tool used only when necessary.

At the same time, a deeper shift will take place; the digital divide will widen. Individuals and small businesses—especially those who built their work around today’s cheap tools—will be the first to lose out.

As access costs double and triple, only the largest players will endure, capable of integrating these tools into their operations and squeezing measurable returns from them. A new kind of digital inequality will emerge—not between those with internet access and those without, but between those who can afford advanced AI and those who must settle for limited or no access at all.

In the Global South, especially in countries like Egypt where digital infrastructure is uneven and budgets are tight, this stratification will be more pronounced.

Freelancers, small media outlets, startups, and educators who have rapidly adopted generative AI tools as low-cost productivity enhancers will find themselves locked out of the AI economy.

What was once a path to competitive parity may soon become a structural disadvantage, deepening both economic and cognitive inequalities.

A generation’s access to creativity, education, and opportunity may be rationed by the price of a token.

The collapse of the generative AI house of cards won’t look like a wave of layoffs. It will take the form of a pricing shock that forces us to reconsider our understanding of the technology. Its magic will fade, and it will become a costly industrial commodity, concentrated in the hands of those who can pay the true bill.

The real question is not if, but when, we’ll receive the first invoice in our inbox.

Until then, we must revisit the personal decisions we’re making around our work and the skills we aim to develop. Because especially in the Global South, the current honeymoon with AI won’t last. This brief moment of accessibility is not the new normal—it is the calm before the contraction.