Parliament Diaries| Accountability offline as Ramses blaze paralyzes Egypt

I was cut off from the world for three straight hours on Tuesday during the emergency meeting of Parliament’s Communications and Information Technology Committee/CITC. I lost internet access. I couldn’t send out updates the way I usually do, while colleagues around me kept their coverage flowing through other mobile networks.

My outage—and the fact that I couldn’t even place a phone call to the newsroom—coincided with the government defending its supposedly extraordinary capacity to restore communications and internet services. The irony bordered on surreal.

During the morning plenary session the Parliament erupted over the fire at Ramses Central Exchange, which paralyzed emergency hotlines, ambulance services, banking, and e-payment systems. It summoned the minister of communications that same day to respond to urgent statements and questions from MPs.

Adding to the absurdity, Parliament’s own digital platform—used by MPs to submit oversight requests and proposed amendments to draft laws—went down. It’s the same system they’ve relied on since 2016.

Blaming the pipes

The CIC committee meeting began that afternoon, after the plenary session concluded and Parliament formally wrapped up its fifth legislative session—contrary to the call from opposition MP Diaa El-Din Dawood, who had demanded that the parliament convention remains until those responsible for the fire were held accountable.

The meeting opened with a minute of silence for the victims. Committee chair Ahmed Badawy then gave the floor to majority leader Abdel Hadi El-Qasabi, who requested an explanation and how such a disaster could be prevented from recurring. The minister immediately responded—before hearing from the rest of the MPs.

Communications Minister Amr Talaat explained the cause of the fire while firmly denying that the communications system is wholly reliant on the Ramses exchange. “It’s an important node, but just one part of a complex national network connecting multiple central offices,” he said.

The blaze began on the seventh floor, sparked by a device in one of the server rooms, he explained. “The room has smoke detectors, which triggered an alarm. Our colleagues rushed in to put the fire out.”

There are, according to the minister, fire suppression systems in place. But he attributed the rapid spread of flames to bad luck “The server was connected to a bundle of cables—both power and data—running through conduits. That allowed the fire to spread quickly through the pipes.”

As the flames advanced, “our colleagues panicked and quit trying to extinguish the fire themselves, so they called Civil Defense,” said Talaat who had been abroad at the time, but cut his trip short and arrived on site at 3 am. “Civil Defense reached the scene at 5:30 pm. They tried to put the fire out, but the it spread through those same pipes carrying wires across the entire floor.”

He finally admitted, “The fire suppression system was activated, but it was no match for the blaze.”

I’m not well-versed in the technical details—pipes, wires, fire suppression chemicals—but I was struck by how the minister kept talking without once acknowledging the obvious; the system wasn’t designed to handle a fire erupting in the infrastructure it was meant to protect. He didn’t pause for a moment to reflect on his own admission about the system’s inadequacy.

Record-breaking performance!

When the going gets tough, ministers reliably deliver quotes destined for the annals of tragicomic history. We saw it after the Regional Ring Road disaster, when the transport minister wondered aloud, “What crime have we committed?” And it happened again on Tuesday with the communications minister.

Talaat admitted that services were affected, but then pointed to the buzz on social media as proof the internet was functioning well. “Yes, the service was disrupted. But it kept going. You all saw the discussions and arguments and criticism shared by thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, online,” he said.

“If this central office were the backbone of the internet, those conversations wouldn’t have happened. But they did. The internet was functioning efficiently. In fact, its efficiency improved.”

Plan C

People were left wondering whether the government had any kind of crisis management plan. And the answer—surprisingly—was yes. Despite the outage and service disruptions, the government said it had a plan, and it was executed.

Talaat explained that the ministry works with three contingency plans “Plan A is to restore service from the affected exchange. But we discovered it was beyond repair. Plan B covers scenarios where a node is damaged but still partly functional. But we had to activate Plan C—taking the exchange entirely offline and migrating all services and traffic elsewhere.”

He justified the delay in restoring services by saying, “There’s no button or switch that can immediately redirect internet traffic. The process is technically complex, and we began immediately once it was clear the exchange couldn’t be salvaged.”

Political responsibility, anyone?

Telecom Egypt's CEO Mohamed Nasr spent his time echoing the minister, throwing around English acronyms for fire suppression materials and reciting the details of Plan C. That’s when MP Diaa El-Din Dawood cut him off “Do you feel even a hint of responsibility? You’re part of this disaster. Show some contrition.”

But Nasr, like the rest of the officials, deflected. Parliamentary Affairs Minister Mahmoud Fawzy offered a blanket statement: “We take responsibility.”

MP Ahmed El-Segini argued that the company had failed to follow proper fire safety codes. “The Israeli-Iranian cyberwar proved that we live in a world where digital infrastructure is a national security issue. We’re a target. We need to know the science.” He reminded the officials that scientific standards must be followed.

MP Amr Darwish echoed the criticism, questioning why effective civil defense codes weren’t applied. “What do you make of government agencies that have been out of service for over 24 hours? How does a fire in central Cairo knock out service in Upper Egypt? Why didn’t you distribute your network load? It’s been 24 hours and you’re still migrating traffic?”

MP Mohamed Abdel Aziz objected to drowning lawmakers in technical jargon, highlighting the core failure “The building wasn’t designed to contain a fire. The government bears political responsibility. It failed to manage the crisis.”

The opposition’s comments conveyed despair that anyone would ever be held accountable. Disaster after disaster, and still nothing.

Wafd Party MP Mohamed Abdel-Aleem Dawoud mocked the government’s calm demeanor. “No one’s going to be held accountable. When was the last time that happened? Maybe a low-level employee or a driver, like after the Regional Ring Road crash. But the government? They’re untouchable.”

He contrasted Egypt’s situation with that of war-torn countries in the region “Even countries at war aren’t as paralyzed as we are.”

Where is the prime minister?

Every time a disaster strikes, MP Diaa El-Din Dawood insists that the prime minister must appear before Parliament. He repeated that again on Tuesday: “The prime minister treats this Parliament with contempt. That’s the painful truth. What’s worse is that it is ongoing.”

Minister Fawzy pushed back, stressing that “PM Madbouly deeply respects Parliament and the government is fully committed to appearing before it and its committees.” He added, “The PM has never been summoned and failed to appear.”

He clarified that the PM's presence is always contingent on an official request from the House, a request Dawood made repeatedly, but the House chief never approved.

Dawood wasn’t convinced. His anxiety only grew. “There’s political responsibility and legal responsibility. We trust the Public Prosecutor with the legal. But here in Parliament, it’s our job to identify who bears the political burden,” he said. “No one resigns. No one is held accountable.”

The government’s attorney

Committee chair Ahmed Badawy opened the session by thanking the Ministry of Interior and the Civil Defense. But MP Freddy El-Bayadi of the Social Democratic Party raised a concern: Civil Defense lacks sufficient resources.

El-Bayadi pointed out the futility of using outdated firefighting techniques in the face of a fast-moving blaze. Why didn’t they deploy helicopters?

Badawy interrupted, jumping to defend Civil Defense. El-Bayadi clarified that he meant no disrespect to the personnel, only to their limited resources. Badawy persisted “We’re discussing an actual event here, not opinions.”

Opposition MPs Abdel-Moneim Imam and Atef El-Maghawry objected to the chair’s interruption. Imam said, “Let the government respond.” El-Maghawry added, “You’re here to run the meeting. Let the government defend itself.”

Did InstaPay work?

Deputy Minister of Communications Raafat Hindy tried to showcase the ministry’s success in restoring services. “All banking operations are back online. Even the last one—the National Bank of Egypt—has reopened its branches,” he said. As for e-payments, “We tested InstaPay. We made symbolic transfers. All the banks worked—except the National Bank of Egypt.”

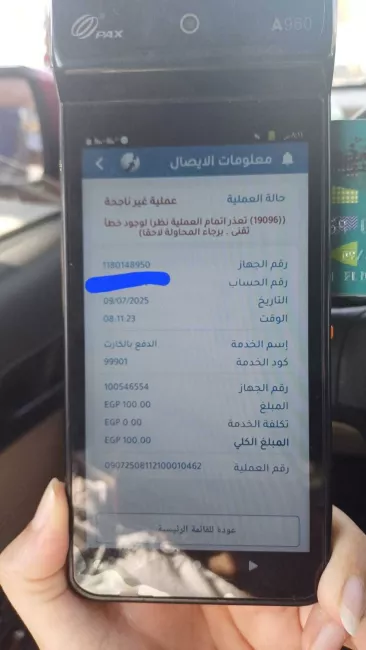

Amid MPs’ skepticism, Minister Fawzy pulled out his phone, successfully transferred 100 pounds to his son through InstaPay, and showed them the confirmation message. But a colleague sitting next to me tried the same thing—and failed.

The government doesn’t seem to realize that the services it boasts restoring are still unreliable—depending on the network, the bank, and the app.

Hindy boasted, “We managed to migrate all these users in 24 hours. Given the scale of the disaster, that’s fast. These are international standards we’re talking about.” Then, trying to sound more empathetic, he added, “Yes, the situation is painful. But by international standards, for a country the size of Egypt, this is fast.”

Then came the bitter comedy when Hindy blamed the victims, “Part of the reason some customers don’t have service yet is their own choice of providers and their infrastructure.” Some providers, he said, weren’t set up with fallback systems. MP El-Segini cut him off, furious, “And whose responsibility is that? If a licensed company’s network design can’t meet its obligations, isn’t that on you?”

Hindy replied, “The National Telecom Regulatory Authority is responsible for oversight.”

Unanswered questions

MPs raised a series of questions that went ignored. MP Amira El-Adly asked, “How much did this cost us? Who will compensate the public for their losses?” Others asked what steps the government would take to prevent future disasters, secure sensitive data, and upgrade infrastructure in a world of information warfare and hybrid threats.

But bigger questions remained unasked. Why is Telecom Egypt still a monopoly? It remains the core service provider, while private companies are little more than distributors.

No one asked what proportion of national data flows through the Ramses exchange. No one held the minister accountable for the investments they approved in the national budget—funds earmarked for network security, infrastructure upgrades, and data center diversification. Now we see how fragile the system really is.

As usual, the meeting ended with a collective shrug. “Let bygones be bygones.” No one will be held to account. The government will submit a detailed plan to Parliament, promising never to let it happen again.

The following morning, while driving to work, I stopped at the Mobil station in Giza’s Remaya Square for car gas. I tried to pay with my debit card. The transaction failed. Fawry machines were still down.