Which Civil Society monitors elections in Egypt

The witnesses who never saw a thing

With credentials issued to 56 organizations and associations, the National Election Authority/NEA promised a network of “eyes and ears” to safeguard transparency and monitor violations in Egypt’s 2025 Senate elections. Over two days, Aug 3-4, voters filed into 8,825 polling stations spread across the country for the first round.

But did this roster of accredited monitors have the expertise and independence needed for such a pivotal role? Al Manassa reviewed the list and found that many lacked a verifiable track record — or even a visible institutional presence.

Only a few of the 56 organizations had functioning websites. Most had no publicly available reports, no published election-monitoring work, and no institutional footprint beyond Facebook pages or occasional statements given to the press.

Yet the gaps were not limited to inexperience.

Top titles, phantom institutions

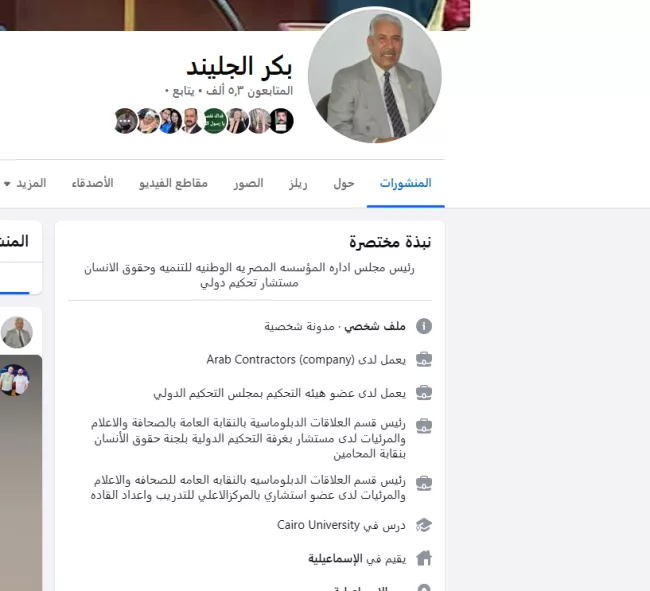

One accredited group, the Egypt National Foundation for Development and Human Rights in Ismailia, is headed by Bakr El-Galind, who describes himself on Facebook with an array of lofty titles, including “Head of the Diplomatic Relations Department at the General Syndicate for Journalism, Media, and Visuals.”

That syndicate, however, doesn’t exist. As the head of Egypt’s official journalists’ union Khaled Elbalshy told Al Manassa, “It’s a fake entity with no connection to the legitimate union.” Magdy Badawy, deputy head of the Egyptian Trade Union Federation, confirmed: “There is no syndicate with this name under the federation.”

A trawl through the group’s Facebook page revealed no prior election-monitoring reports. In 2023, the foundation’s election-related activity consisted of just two Facebook posts, both re-posted videos shot outside polling stations, featuring party loyalists praising “wonderful democratic conditions” as loudspeakers blared and Nation’s Future party organizers worked the crowd.

Invented ranks

Two other groups on the NEA’s list —the Civil Alliance for Human Rights and the Egyptian Amnesty Association— share the same leader: Mohamed Fawaz. On Facebook, Fawaz styles himself “Ambassador Dr.” and “President of the Egyptian Front for Supporting the Army and Police,” as well as “Head of the Syndicate of Human Rights Advocates in Egypt.”

But neither Egypt’s Foreign Ministry records nor its diplomatic appointments bulletins show any evidence that Fawaz ever served as an ambassador. And the so-called Syndicate of Human Rights Advocates has no legal standing in any recognized professional or civil society structure within the country.

In Nov. 2019, Fawaz joined a heavily publicized Interior Ministry-organized visit to Borg El-Arab Prison — a trip covered in state-aligned media with glowing descriptions of conditions inside. This was at a time when the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms described the same prison as a site of systematic abuse under National Security orders.

A doctorate for the asking

Neven Gamil, head of the accredited Nebras Al-Salam Foundation, ran unsuccessfully for the Senate in 2020 on the Egypt Liberation Party ticket. Two years later, she posted what she called a “public statement” offering to accept any government position “in service of my country.”

Now a women’s affairs secretary for the pro-government Republican People’s Party, Gamil’s Facebook page showcases three “honorary doctorate” certificates, which she uses to prefix her name with “Prof. Dr.”

One purportedly came from an institution called Elizabeth College in Britain; a name shared by various pre-university schools. A reverse image search of the certificate shows identical templates awarded to recipients worldwide, while its listed London address turns out to be a virtual office.

In 2023, Nebras Al-Salam itself awarded five honorary doctorates to participants in one of its events.

Another group on the NEA’s list, the Egyptian Organization for Human Rights and Development, promotes (and sells!) honorary doctorates from an entity using Harvard University’s name and logo, accompanied by the promise that the degree requires “no study… no exam!”

Tracing the entity allegedly affiliated with Harvard reveals it was nothing more than a former name for a page called “Sawt Al-Nas Al-Hurr” or The Free Voice of the People.

The monitor who doesn’t see

The absence of documented violations is nothing new. In past elections, many accredited groups either ignored or narrowed the definition of malpractice to exclude major infractions.

In the 2020 parliamentary elections, the National Council for Human Rights noted extensive vote-buying. Yet the Ibn El-Nile Foundation’s representative justified not reporting such cases by saying, “It’s not our role if it happens outside polling stations.” He was not alone.

Other groups, like the Egypt Peace Foundation and the National Foundation, issued blanket endorsements of all past elections. The Union of Associations posted Facebook “clean bill” declarations for entire election cycles.

Even Ayadi Masreya (Egyptian Hands), which has an actual website and publications, announced that its participation was “about engaging, not just monitoring.” Since 2020, it has recorded no negative observations on any elections.

Some, like the Egypt Alliance for Human Rights, barely engaged at all: its only Facebook post about the 2024 presidential elections was a neighborhood visit declaring “no irregularities.”

And Hemaia’s/Protection Facebook page contained just one election-related post; a photo-op of its leaders voting for President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi.

Not all quiet

There are exceptions though. The Egyptian Youth Council reported irregularities in the 2018 presidential race and again in the 2020 Senate elections, including partisan campaigning outside polling stations, vote-mobilization with loudspeakers, and failure to use indelible ink.

Groups like Maat, Partners for Transparency, and the Dialogue Forum for Development and Human Rights maintain professional websites, publish reports, and engage in research.

In 2023, Maat and Partners for Transparency co-founded Nazaha/Integrity Coalition with four foreign organizations from Greece, Ghana, Uganda, and Romania, to monitor the 2024 presidential election. Still, the coalition reported no violations.

The same four foreign organizations were accredited to monitor Egypt’s 2025 Senate elections, but international oversight remained minimal throughout the vote.

As Mohamed Zaree of the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies explained, Egypt’s political climate has driven many independent rights groups into closure or exile. “Even the EU and the Carter Center said they wouldn’t monitor elections after 2014,” he told Al Manassa.

The Dialogue Forum for Development and Human Rights issued a report on the 2024 presidential election -held in late 2023- describing it as “serious.” But an analysis of the report, from headline to conclusions, reveals a clear tilt towards the government.

It selectively highlighted government achievements while omitting any mention of the economic crises or the closure of public space. It praised candidate Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s campaign while sidelining other candidates entirely.

The contrast with independent monitors was stark.

The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms’ report on the same election documented a series of violations on the very first day, including direct campaigning for El-Sisi outside polling stations, organized voter mobilization, and the distribution of cash and food to sway votes.

The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights presented a similar contradiction in its 2020 Senate election report. On one hand, it recorded serious violations such as vote-buying, distribution of food and shopping vouchers linked to specific candidates, and the use of vehicles with loudspeakers threatening citizens with fines if they failed to vote. On the other, it downplayed these as activities occurring “outside polling stations” and offered unqualified praise for the integrity of the voting process inside.

From charity to credentials

The irony lies in the fact that, according to an EU report, the main reason the High Elections Committee rejected monitoring requests from 32 associations in 2014 was lack of experience. Yet that applies to many of the associations currently approved by the NEA, which replaced the High Elections Committee in 2017.

A review of the NEA’s approved list shows that many of the accredited groups are in fact small-scale local charities with no record of election monitoring whatsoever.

These include, for example, the Youth of the Generation Association for Development in Cairo’s Al-Duweiqa district, which focuses on distributing aid. Also the Youth of the Future Association in Menoufiya’s Manshat Ghamreen village with purely charitable activities, and the Youth of Sohag for Charitable Work Association. Others are orphan care groups such as the Al-Sondos Foundation for orphans with special needs, or health and development charities like the Egypt for Health and Sustainable Development Foundation.

Most have no online presence, no published reports, and no record of training election observers.

In one incident, the head of the Independents International Foundation declined answering our questions, on the grounds that the organization had decided not to monitor the elections at all this year despite receiving official accreditation.

Some entities exist only as names, such as the Ayoun Center for Studies, the National Human Rights Association in the Red Sea, or the Jesr Association, with no functioning website, active Facebook page, or public record of any election-related activity.

Friendly faces

The picture that emerges is one of accreditation granted to groups with little experience, little transparency, and in many cases close ties to the state or ruling parties. As Hossam Bahgat, director of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, put it, “These are organizations we’ve never heard of — or that are friends of the state.”

The NEA did not respond to Al Manassa’s request for comment on its selection criteria.