Interview| Basel Ramsis on Gaza, the flotilla, and a journey cut short

“Those on the flotilla aren’t the heroes… Gaza is”

I made an unwitting error while editing the last piece in the To Palestine series that documented Egyptian filmmaker and writer Basel Ramsis’s journey from Barcelona aboard Yulara/Al-Nasra towards Gaza with the Global Sumud Flotilla. The Arabic text ran under the title “The Last Article,” though his original title was “The Final Days.”

The mistake felt like an unwelcome omen preceding what Basel calls a “stupid fluke” that marked the premature end of his voyage, just before the mission entered its final, most dangerous leg towards the besieged strip.

Ramsis was forced to return weighed down by physical injuries and psychological exhaustion, which meant he could not write a closing article for the series. Our ongoing check-ins over recent days opened a window; my questions nudged his storytelling back to life. This is the story he told.

The accident

Following a decision by the medical team, Basel left the flotilla on Sept. 26 when it stopped at the island of Crete. He posted on Facebook that he was disembarking due to injury.

His post caused confusion. Some assumed he had been hurt in the drone attack on the flotilla two days earlier. He clarified from the outset, “The injuries weren’t from the drone attack. No one was hurt that night.”

“On the morning of the twenty-fourth, I made a big pot of coffee and set it on a small table in a cramped spot at the stern of Yulara/Al-Nasra. The boat rocked with the waves and the coffee spilled on me. I ended up with several small burns, but the two on my right arm and my left foot were serious.”

It took about an hour and a half to see how bad they were. Then an Italian doctor from an international organization accompanying the flotilla came from another boat, examined the burns, cleaned them, and applied ointment. “He was very clear that burns carry a constant risk of infection. He said we had to decide immediately whether I would continue or not. I made it clear that I would continue. The burns weren’t going to stop me.”

Two days later, that seemingly final decision unraveled. When the flotilla reached Crete, the Family boat broke down forcing those onboard to move to other vessels. “It was time to change the dressing. A colleague on Yulara removed the gauze and saw the wound. It was bad and too much for her to handle. We asked for a doctor, and learned they’d been discussing my case for two days based on photos.”

Dr. Othman, a Turkish member of the flotilla, hit Basel with the news that the burn on the foot “was second degree and at high risk of infection. Right next to the ankle joint, if infection sets in, it could affect the joint permanently. And if arrested by Israel, they wouldn’t treat the wound or the infection.”

“On Sept. 26, from eight in the morning until five in the evening, I kept coming to opposite conclusions,” he recalled. The struggle over whether to keep going or leave the boat was influenced by “the doctors’ advice, calls with other doctors and my family, and the thoughts of my shipmates,” until the medical committee finally issued its ruling: he had to disembark.

“My comrades, who insisted I stay, said they would cover my duties, look after me, and share responsibility with me.” Given this support, Basel pushed back. To reduce the risk of infection, Basel proposed transferring from Yulara to another boat that had a doctor on board . But the team’s duty of care, especially as the flotilla moved into the final, high-risk stage, settled it.

The accident cut short Basel’s most important mission since he engaged with politics in the 1990s. “I disembarked at Crete, went from the port to the airport, then to Barcelona, where I went to an emergency burns unit.”

The hospital report classified the burns as second degree, with possible areas of third-degree damage that might require a minor skin graft. “‘But only time will tell,’ they said. ‘We’ll see whether the wound heals on its own over the coming weeks.’”

The trauma of leaving

Basel struggled to describe how he felt as he stepped off the boat. “I was in shock. A moment of trauma. There was a lot I wasn’t taking in, and my emotions were all over the place. Beyond the physical pain, my heart and mind weren’t in a good way. I was just so disappointed.”

“A stupid fluke intervened and derailed the path that began on Aug. 27 when I reached Barcelona, and on Aug. 31 when I boarded the boat. And it was an exhausting path,” he said. “Life on a small boat was harder than I imagined, physically, mentally, and emotionally.” Then he added, “But it was the path I chose. I was at peace with the mission and able to write, publish, and communicate with people to say there’s an Egyptian on the flotilla.”

Basel realizes that over the coming weeks he will have to live with and accept having left before the dangerous phase. “How do I process this moment, this trauma?” he asked, postponing the reckoning for now. “What matters most is the mission, and the people on the boats heading to Gaza. Gaza is the main goal. It’s the hero, and it must remain.”

He sees the flotilla as a powerful symbol of the huge and impressive global solidarity movement with the Palestinian people. “The core aim is to talk about Gaza and the flotilla; our right to break the siege, stop the genocide, reach Gaza, and prevent the annihilation of the Palestinian people.”

The poetics of the dispatches

Basel is aware that the dispatches Al Manassa published over the past month were “more lyrical and emotional” than his weekly articles that readers are used to.

“I usually write at home, in a closed room, with my books, the internet, my rituals, my coffee, everything set up.” It was nothing like that on the Yulara.

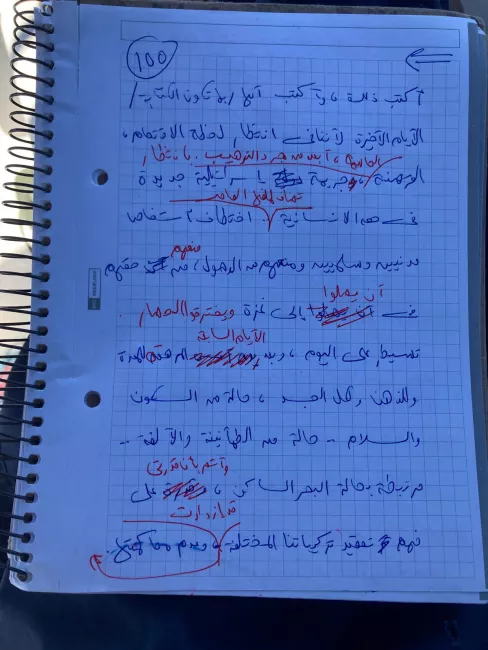

“For the first time in my life, I wrote sitting uncomfortably with a notebook on my lap and six people around me making noise, talking, playing music, asking me to do things like ‘Basel, grab that rope.’ I’d get up, do it, then come back.”

He sent his pieces as photos and voice notes for review and publication. “They were handwritten, then I made corrections in red pen on a second reading, but not with the usual level of concentration.”

Working hours were scarce. “From four in the afternoon there was no light. I couldn’t read or write until four the next day. In those twelve hours, there were daily duties like washing dishes and standing watch.”

He distinguishes between his weekly op-eds for Al Manassa, which are intended to make readers think and draw their own conclusions, while revisiting parts of our history and their impact on Palestine, like his Camp David pieces, and the emotional letters from the boat, where the filmmaker eclipsed the columnist. “I notice who’s with me, what they’re doing, how they look, what we’re feeling, the day-to-day details.”

Through that quick, unvarnished writing, he tried to convey “emotional reactions, feelings, and tears so that the concrete details had some meaning, like my wristwatch and Mohammed’s keffiyeh.”

In the heat of this battle, Basel chose to speak to the reader’s emotions more than the intellect. “I couldn’t help it,” he said. “The messages I received, from friends, family, strangers, were waves of emotional energy.”

Largest global solidarity since Vietnam

The film-maker and writer considers the current, broad-based popular solidarity, from Spain’s abandoning of a cycling race to Italy’s general strike, as “the most important political and moral battle against Israeli aggression since 1948.”

After a month aboard, he doesn’t deny there are “comments and criticisms,” shared by many participants, about the work of the flotilla’s higher coordinating committee . However, he prefers not to air them now. “Criticism must come at the right time and in the right form, not as a gift to Israel or its allies, who are waiting to use it against the flotilla, and worse, against the Palestinian people and their cause, and against global solidarity in the middle of the fight.”

He points to the disinformation war waged everyday by forces hostile to the flotilla, claims that “we’re vacationing in Ibiza, drinking alcohol, using drugs, that we’re high all the time.” His response is simple: “Not a single boat carries a drop of alcohol or any drug. None.”

Final messages

Basel, who has devoted his weekly Al Manassa essays to Palestine since Oct. 7, 2023 believes he has no right to send a message to the Palestinian people. “No one has that right. No one is qualified to address a people and tell them what they should hear, least of all the Palestinian people.”

He recalls coordinators asking participants to record videos addressed to Gaza during the voyage. He refused. “I’m not the white man going to save the people of Gaza.” The Palestinian people have taught the world the meaning of resistance since 1936, he said, and they alone understand the flotilla’s purpose: “They’re waiting for it and welcoming it. The only party with the authority to tell us not to come to Gaza is the Palestinian people.” They are, he stressed, “the core wager and central actor.”

Basel addressed a message to the flotilla’s participants, especially his companions on Yulara/Al-Nasra. “They were my family for a month, and they will remain my family. An experience like this leaves a mark, on the spirit, the mind, and, in my case, on the body too.”

He shared a brief note he sent to his shipmates. “It’s an honor that I was part of Yulara for 27 days. The crucial moment is now. You have entered the danger zone; the world’s eyes are on Gaza and on the flotilla. We are with you; our hearts are with you and for you to reach Gaza safely and return home safely.”

For Ramsis, hope narrows to a single point: “Reaching Gaza and opening a permanent humanitarian corridor.” That the mission he had to leave may yet be completed.