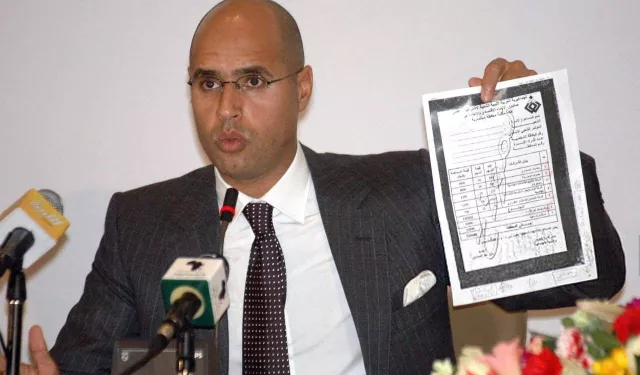

Explainer| Saif Al-Islam Gaddafi assassinated. Who wanted him gone, and what happens next?

Saif Al-Islam Gaddafi, the second son of Libya’s former ruler Muammar Gaddafi, was assassinated late Tuesday night, Feb. 3, in an attack that immediately reignited old rivalries and new suspicions across the country’s fractured political landscape.

According to his political team and lawyer, a four-man commando unit stormed his residence in the western city of Zintan after disabling its surveillance system, killing him with gunfire before fleeing the scene. Libya’s attorney general has opened a criminal investigation, but no group has claimed responsibility so far.

Once seen as the would-be reformist heir to his father’s rule and later a symbol of defiant continuity with the Gaddafi era, Saif occupied a uniquely volatile position in Libya’s post-2011 politics. His death eliminates a major political figure, raising urgent questions about who orchestrated the assassination, their motives, and the implications of his absence in a divided nation.

Who was Saif Al-Islam Gaddafi, and why is he important?

Before the 2011 Libyan revolution, Saif was the member of the Gaddafi family most responsible for cultivating relationships with foreign leaders. A Western-educated reformist, he helped spearhead Libya’s rapprochement with Europe and the United States, including negotiations over compensation related to the Lockerbie bombing and support for dismantling Libya’s weapons of mass destruction program. For many foreign capitals, he functioned as the modernizing face of the Gaddafi regime, publicly talking about constitutional change and civil society within his father’s authoritarian system.

When protests erupted in 2011, that modern facade gave way to a hardline defense of the regime. In televised speeches, Saif threatened a violent crackdown and warned of “rivers of blood,” pledging to fight to preserve his father’s rule while blaming the uprising on foreign conspiracies. After the fall of Tripoli and his father’s death, he was captured by Zintan-based fighters while trying to flee towards Niger. In 2015, a Tripoli court sentenced him to death in absentia, but Zintan authorities did not hand him over. He was later reported to have been granted amnesty under a contested general pardon law in 2017.

By 2021, Saif had resurfaced, announcing his candidacy in Libya’s planned presidential elections and presenting himself as the guarantor of a return to Gaddafi-era order and stability. Those elections ultimately did not take place, and he remained a shadowy but influential figure in Libya’s fractured political landscape, unbound by formal institutions yet still commanding loyalty in parts of the country.

What do we know about his assassination?

In January 2026, senior Libyan figures from rival camps held meetings in Paris with French officials. The talks included a visit by Saddam Haftar, deputy commander of Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), to discuss security cooperation and unified governance. These negotiations were part of renewed efforts backed by Western envoys to revive a political process and centralized authority.

Saif was seen by many observers as an unpredictable political figure with residual popular appeal in some areas and tribal networks, but no formal institutional constraints. Several analysts suggested he could either be integrated into such a plan or prevent any concessions that sidelined pro-Gaddafi constituencies.

On the night of Feb. 3, four masked gunmen entered Saif’s home, fatally shooting him and at least three personal guards. The attackers then fled the scene.

Who benefits from his assassination?

With no group claiming responsibility and the investigation in early stages, who is behind the attack remains unclear. However, early analysis by the Robert Lansing Institute for Global Threats and Democracy Studies has outlined several possible perpetrators.

One scenario points to networks aligned with Western-backed or Zintan-based militias that previously held Saif prisoner after 2011. These actors are embedded in local power structures around Zintan and have both the access and the operational capacity to mount such a raid. Removing Saif from the scene could serve to settle internal scores, prevent him from reemerging as a national political figure, or preempt any deal that would have boosted his leverage in a reconfigured political order.

Another possibility is the Tripoli-based government and its allied militias. For them, eliminating Saif would narrow the field of would-be presidential contenders and reduce the risk of a Gaddafi resurgence that would undermine efforts by Western Libya elites to consolidate power. So far, however, no public evidence links Tripoli-aligned security forces to the attack.

The Robert Lansing Institute and other commentators also mention the LNA, Jihadist organizations, and foreign intelligence services as potential but less likely actors. Experts caution that logistical hurdles and the risk of political fallout make these scenarios implausible.

How could his death reshape Libya’s internal power struggles?

Saif’s political stance in recent years placed him at odds with power centers in both eastern and western Libya. He sought to capitalize on the nostalgia of younger Libyans who did not live through his father’s rule but remember relative security compared to recent years of war, positioning himself as an outsider to the fragmented institutions that emerged after 2011.

News of his assassination has already triggered accusations between pro-Gaddafi networks and supporters of Haftar’s eastern front, as well as suspicion toward forces aligned with the internationally recognized government in Tripoli. Libya’s political arena is heavily shaped by tribal alliances, and support for a Gaddafi reemergence, in whatever form, often maps onto these tribal and regional loyalties.

In the short term, groups blamed for Saif’s death could face reprisals, particularly in and around Zintan, where armed factions have long-standing rivalries. This raises the risk of localized escalations that could ripple into wider confrontations if not contained.

In the long-term, Saif’s absence is likely to force a reconfiguration among pro-Gaddafi currents, including arguments over succession and strategy among his remaining family members and tribal allies. If efforts to establish a more unified government proceed, it is probable that the interests of these pro-Gaddafi factions will be deprioritized.

Does Saif’s death change Libya’s political trajectory, or confirm it?

It is unclear whether Libyan authorities will publicly identity perpetrators.

Saif’s death takes one of Libya’s most prominent figures out of the political arena, shifting the balance of power among domestic actors and highlighting the influence of the country’s remaining political players.