Freelance journalists: professionals or impostors?

“I feel like a fifth-tier journalist, not second or even third. Sometimes I’m forced to work under a pen name because I have no institution shielding me. I’m afraid of legal repercussions and have no union protection,” said Mohamed Adel, a young economic journalist.

Adel, who graduated from a media school in 2020, publishes freelance pieces for various Egyptian and international outlets. When he uncovers a significant story, he often opts for a pseudonym, especially when reporting on corruption or politically sensitive economic issues.

Under Egypt’s Journalists Syndicate law, anyone practicing journalism without being a registered syndicate member is considered to be “impersonating a journalist” and is subject to detention. Article 115 stipulates a one-year prison sentence or a fine, not exceeding 300 pounds (about $6), or both penalties.

Due to the stringent conditions for syndicate membership, Adel and hundreds of other journalists are unable to join the union; a step that allows them to change their profession on their national ID to “journalist,” and gain legal and union protections.

“I have a journalism degree and six years of experience, but the syndicate’s 1970s law requires me to work for a print newspaper to qualify for membership,” Adel said.

His fears are compounded by the nature of his reporting, which often involves investigating corruption or tackling contentious topics that many official institutions deliberately obscure from public view. Although he adheres to professional standards, citing verified sources and official statistics, the specter of state retaliation remains constant.

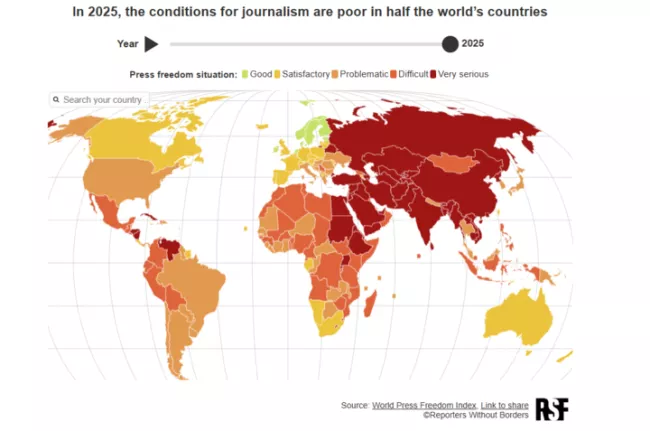

These fears are not unfounded. Reporters Without Borders’ 2024 Press Freedom Index described Egypt as continuing to be “one of the world’s biggest jailers of journalists. The hopes for freedom that accompanied the 2011 revolution now seem distant.”

Egypt’s ranking on the Press Freedom Index dropped from 166 in 2023 to 170 in 2024. The organization stated that almost all Egyptian media “are directly controlled by the state, the intelligence agencies or a handful of wealthy, influential businessmen who are under the government’s thumb. By contrast, media outlets that refuse to submit to censorship are blocked.”

The data shows Egypt’s ranking has continued to deteriorate since the downgrad in 2017 from a “difficult” to a “very serious” country for journalists.

The risk of field reporting

Sarah El-Hareth is in a relatively better position than Adel. She’s a syndicate member and previously worked for a newspaper generally seen as pro-government. She still carries an old press card from that job—an ID that has protected her during several encounters with police since becoming a freelancer.

“Whenever security stops me, the first question is always, ‘Who do you work for?’ When I show them the card they treat me better. That card is my shield, even though I don’t work there anymore,” she said.

Sarah isn’t always spared. While working on a story about Sudanese refugees, police intercepted her near the UNHCR office. “They deleted my photos and videos, held me for a while, then let me go.”

Law No. 180 of 2018 on Press, Media and the Supreme Council for Media Regulation exacerbates the situation. Article 12 states that “journalists have the right to film in public spaces… after obtaining the necessary permits”—a clause that effectively nullifies the right by making it conditional to rarely granted approvals.

Critics argue this clause empties the right of substance by its vague wording and selective enforcement. Instead of protecting journalists, cameras become a liability that grants police permission to obstruct reporting. Authorities rarely issue filming permits and often reject requests verbally without justification.

If this is the situation for employed journalists, one can imagine how dire it is for freelancers outside the syndicate. Legally, they can’t even apply for permits, as they’re considered “impostors.” Their limited options are: risk filming and face legal consequences, use footage already posted by others on social media—undermining credibility—or, avoid visual storytelling altogether.

According to an online survey by Al Manassa involving 50 freelancers: 54% reported filming without permits; 26% used social media images; 10% abandoned stories entirely to avoid risk.

Meanwhile, fears of arrest have grown. In February, during a meeting of the Syndicate's Committee on Freedoms with families of detained journalists, union president Khaled Elbalshy said, “The number of journalists held in pretrial detention remains the syndicate’s greatest wound.” He noted that 24 journalists are currently in pretrial detention, including 15 who should have been released after exceeding the maximum two-years arbitrary detention stipulated in the Criminal Procedure Law.

Suspicious sources

Adel recounts how daily tasks often become uphill battles. Securing a comment from a government official turns into a maneuver because strict rules stipulate that only spokespersons are allowed to speak, and they don't.

“Officials refuse to talk. They insist the spokesperson approves every word before publishing, which is impossible because the spokesperson won’t even speak to us,” he said.

He recalls the usual barrage of questions from sources “Who are you working for? Are you with the Muslim Brotherhood?” He gives a short, bitter laugh “Even if I’m just asking about the budget for a local market, they panic.”

His fear deepens when using a pseudonym. “I’m afraid the source might betray me to the police, especially if the security services call them to ask,” he said. “That might sound far-fetched, but in Egypt, anything is possible.”

Al Manassa's survey found that 20 of the 50 freelancers reported feeling a “lot” of risk from the security authorities while working. Fifteen said they felt “moderately,” at risk, 12 said “slightly,” and just three reported feeling no threat at all—a telling indicator of the climate they operate in.

To reduce risk, Adel has changed how he works. “I now focus on stories that rely on open sources information so I don’t have to contact people. It’s safer, but it also weakens the story. Sometimes it ends up incomplete or just not strong enough.”

Delays and missing payments

Both Adel and Sarah echoed an additional struggle: long delays in publishing and payments.

“I choose outlets that don’t take more than two weeks to publish,” Adel said. “That’s a main criteria for me.” Sarah has less choice. As a single mother, she takes whatever she can get.

Adel likened the wait for publishing to a chronic condition that slowly drains the joy out of journalism. “Sometimes a story comes out after it’s lost its newsy value,” he said.

As a student, Adel tried breaking into traditional newsrooms but faced closed doors “even for unpaid internships.” So he became a journalist through what he calls “the back door,” collaborating with independent outlets.

Over time, freelancing became his preference, even when offered permanent employment. “The salaries are terrible, and there is nothing to learn at traditional newsrooms,” he said.

Investigative journalist Loai Hesham also expressed frustration with the slow pace of independent outlets. “Pitching, waiting for feedback, editing, and publishing, it all takes so long, the story dies.”

Such delays mean more than missing the sweet-spot; they force freelancers to narrow the scope of ideas they can pursue. “I drop a lot of ideas because of time constraints. I end up boxed into topics that aren’t time-sensitive,” Loai said.

Al Manassa’s survey supports Loai’s point. It found that 90% of the sample had at least one story delayed by more than a month. In practice, that means delayed payments, and sometimes, a direct threat to their ability to keep working.

Sarah believes the freelance market is “narrow and limited,” since only a handful of Egyptian, Arab, or international outlets accept freelance stories, and each has its downsides.

“One outlet won’t pay until you publish six pieces. Another takes two weeks to reply, then more time for edits, review, and publishing, and another month to pay. In the end, you get 2,500 to 5,000 pounds (about $50–100), and even that can be delayed another month,” she said with a laugh. “So one story can take three months to get paid. Still, it’s the only way I can work while taking care of my son, who’s in preschool and needs me.”

Loay found little relief at the German outlet he worked with, “the pay was really low, nowhere matching the effort. These institutions bank on the pound being weak against the euro or dollar. But it doesn’t cover the rising costs of living.”

“There’s no health or social insurance. If I get sick and can’t work, my income stops, and no one’s there to protect me,” Loai said.

Adel agreed. “There’s no umbrella or safety net. At any moment, I could be out of the game, unable to keep up with tech.” He added that above all else, journalism drains journalists emotionally.

He feels marginalized. “Even now, as I’m speaking to you, I am thinking that outlets just see me as a ‘contributor’—someone they use when needed but can easily discard. My family sees me as someone who just works online from his bedroom. The state sees me as an impostor. If the syndicate ever recognizes me, they’ll just call me an ‘electronic journalist’ as if I am lesser.”

“I’m scared I’ll wake up one day and realize I’ve become a ghost. I’ve seen brilliant journalists break under the pressure. The profession abused them, stole their good years and gave them nothing. No safety, no recognition.”