A president alone

“What the president said today in Baghdad would have gotten him arrested in Cairo.”

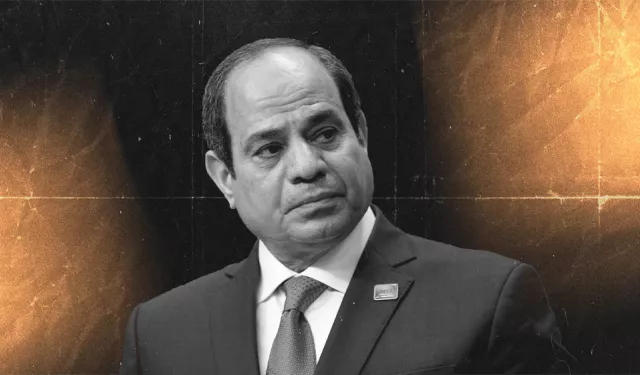

This quip, in Egyptian colloquial Arabic, stood out as the most comically accurate take on President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s speech at the recent Arab League summit—particularly his assertion that peace will not be achieved without the establishment of a Palestinian state, even if every Arab country normalizes ties with Israel.

This sarcastic comment cannot be separated from the president’s stern, grim expressions during the summit, nor from another scene just hours earlier: Trump’s visit to the Gulf, in which he bypassed Egypt and did not invite el-Sisi to meet him.

The joke, when seen alongside these two moments, reflects a bleak truth: El-Sisi stood alone, with no one to talk to and no one to listen to him. He appeared painfully aware that the region’s future was being charted without him, and in a way that ignores the largest Arab country, the one he leads.

The president found himself alone in Baghdad, given the absence of the leaders of the regional heavyweights. The Emir of Qatar left early, and even Iraq, the host, can hardly be described as a major regional power, having been gutted and fractured over three decades, with the complicity of the Arab order, Egypt included.

El-Sisi’s speech reflected not power but quiet desperation. He stressed what everyone already knows: this is a pivotal moment for the region. He implicitly condemned the Abraham Accords, which are being reinvigorated despite the genocide, and warned that normalization will not yield peace.

Yet what makes the irony unbearable is that some of those who share El-Sisi’s stance—that peace cannot come without justice for Palestinians—are languishing in his own prisons for protesting to express exactly that view.

Perhaps the most tragic moment came when El-Sisi appealed to Trump, a man openly advocating for the displacement of Palestinians and envisioning Gaza as a beachfront for American developers, urging him to channel his inner Jimmy Carter and create a moment similar to what happened in the late seventies, by sponsoring a historic agreement that ends the conflict in the Middle East based on the two-state solution; a now impossible prospect.

A trap made in Egypt

Just days earlier, on Nakba Day, the state-owned Al-Ahram buried a supposedly impassioned headline on page five: “77 years and the wound is still bleeding. Palestinians continue to resist the occupation and ongoing extermination. One chant remains in memory of the Nakba: We will never leave!”

A telling headline for a clear dilemma; it tries to be stark, yet it’s relegated to page five, to be seen by as few as possible. It attempts to convey the scale of the current catastrophe but, at the same time, dilutes responsibility and obscures those to blame for making it worse. For the wound that still bleeds has far surpassed the wound inflicted 77 years ago, after dozens of successive wounds have been added, widening and deepening the old one. Partial responsibility for the festering expansion of this wound lies with the Egyptian regime.

El-Sisi’s isolation in Baghdad mirrors this broader dilemma. Trump toured the Gulf, visiting Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia, but none of their rulers saw fit to invite El-Sisi to join them and the US President. Not one of them gave him the opportunity to state the fact that any arrangements for the region with any prospect of success must involve Egypt.

No, they did not invite him and did not engage him. Instead, they embraced former terrorist Ahmed Al-Sharaa, the kind of individual that the Egyptian president and all the institutions of his state have spent 12 years fighting.

These Gulf leaders invited him to repay the favor that brought him to power, and, if he wishes to remain in power, to set his government on the path of normalization and the Abraham Accords. Trump, in their presence, declared that the US should control Gaza, and no one pushed back.

El-Sisi’s regime, like its Gulf allies, seeks to destroy regional resistance movements and clip the wings of the Palestinians. But Cairo also knows that fully clipping Palestinian wings would be a national security disaster for Egypt.

The Egyptian state is well aware of the fine line it has walked for 50 years—engaging with Israel diplomatically while keeping normalization limited and restrained to avoid inflaming and humiliating the Egyptian street. The contrast with the Gulf’s flamboyant embrace of Israel is stark.

However, the fundamental difference between El-Sisi’s authority and the authority of those Gulf states was amply demonstrated in the imagery of the Baghdad summit. El-Sisi’s rule is based on the Egyptian state’s historical knowledge of the region and how to deal with it. Even if absent or wrong, Egypt is conscious of the deep regional dimensions to the Palestinian cause. The Gulf states, in contrast, lack such a tradition of statecraft to fall back on.

The UAE, for example, act more like a multinational corporation than a traditional state. As for Syria, once a bastion of Arab resistance, it has collapsed into internal chaos, with its president and his militias unable to distinguish between preserving the state and preserving Assad’s rule.

Cairo also understands something the Gulf may not. The forced displacement of Palestinians, no matter to where and in what form, and further months of genocide could ignite the Middle East. The region is a volatile mosaic of conflicting interests, and many groups will not accept transfer and the elimination of the Palestinian cause. Egypt’s resistance to these policies is not about principle or ethics, but about preventing a series of explosive reactions that will threaten its existence.

El-Sisi, recognizing his regional isolation, likely also recognized the deeper rift. His regime’s long-term calculations differ from those of the UAE, and the Gulf sheikhdoms and kingdoms, which he imagined would forever ensure the continuity and stability of his rule.

He also realized the differences in short-term assessments: his regime, like many around the world, is trying to avoid a confrontation with the Trump administration for as long as possible, maneuvering until the storm passes or the real estate mogul’s term ends, searching for more robust relationships with the European Union or other centers of power. Meanwhile, the rulers of the Gulf, whose oil and gas everyone needs, deal with all global poles but are banking heavily on Trump.

The question remains: Has El-Sisi realized that he’s caught in a three-sided trap of his own making?

One side, El-Sisi inherited, was put in place by Sadat: Egypt’s dependence on US military and economic aid. In recent weeks, it might have been possible to consider abandoning it, if he had any sign that the Gulf would step in to fully replace American support.

The other two side to the trap are of El-Sisi’s own construction.

One is Egypt’s total reliance on the Gulf to solve its economic crises—through selling land, infrastructure, and state assets in a desperate bid to stay afloat, imagining this would make him a “precious ally” with some say over the region’s future and a permanent seat at the table.

The third side of the trap relates to the joke at the beginning of this article. The Sisi regime has not only crushed pro-Palestine voices and anti-normalization protests. It uses draconian oppression against anyone who dares to think or speak out, adopting fear as the key tool to ensure the regime’s survival.

Flying hotels to the Gazan Riviera

As Gaza starves, Qatar gifted Trump a flying palace—the world’s most expensive, and arguably most garish and tasteless jetliner. Gilded to the point of nausea, it matches the tastes of the corrupt realtor in charge of the US and, naturally, the tastes of many emirs, sheikhs, and monarchs.

But the more revealing symbol may be another aircraft, one that features in a series of commercials for Emirates Airlines starring Spanish actress Penélope Cruz. Cruz tells us that she’s always going from hotel to hotel and that this luxury aircraft is “a flying hotel”, as she gushes over the magic of taking a shower up in the clouds.

Without delving into the details of the “supposed” progressive stances of Cruz, her husband Javier Bardem, and their family, and without stressing that their global success guarantees them eternal wealth and no need for such ads, I will simply point out that this promo expresses an important differences between the Gulf kingdoms and emirates, and the Egyptian state.

The subtext is clear: Gulf monarchies can buy everyone — actors, artists, athletes, politicians. Egypt cannot afford anyone. Even Mo Salah is far beyond the reach of local clubs. The Egyptian authorities can only buy local and second-rate entertainers, intellectuals, and media figures to work for them. Then, they realize those influencers have no real influence or credibility, at home or abroad.

The sarcastic clown’s face—the regime’s own reflection—stares back at the trap it laid for itself. A grotesque, ironic image of a government peering into the consequences of its illusions: expecting to reap endless Gulf wealth in return for loyalty, imagining it could become an indispensable partner in shaping the region. Instead, it now watches, bewildered, as the Gulf monarchies lavish trillions on Trump’s America—gifts handed over for a single visit—while Egypt is left empty-handed and sidelined.

As for the non-sarcastic, rather tragic, side, it concerns the oppression and tyranny of the President’s trap, which he doesn’t know how to escape. The President said in Baghdad “I reiterate with absolute conviction that even if Israel succeeds in forging normalization agreements with all Arab states, a durable, just, and comprehensive peace in the Middle East will remain fundamentally unattainable without the establishment of a Palestinian State, in accordance with the resolutions of international legitimacy.”

What if the president had said this while genuine popular protests—not choreographed ones orchestrated by security agencies—roared in Egypt’s streets? What if Egyptians were allowed to demand freezing relations with Israel, or call for free passage of aid and medical convoys to Gaza without Israel’s permission? What if?

Egyptians, Arabs, Europeans, Americans, and Israelis all know when Egypt’s protests are orchestrated by the state’s security apparatus and when they reflect genuine public anger. They know that staged demonstrations after Eid prayers and carefully selected convoys to Rafah are meaningless when ordinary Egyptians are barred from reaching the border themselves. They also know that if the regime had relaxed its grip and allowed the street to express its rage and solidarity with Gaza, it would have regained the one formidable card Egypt has always held: its popular, political, and historical weight. That could have changed everything.

But the heart of the trap is this: the president’s regime knows it has forfeited that decisive card. It knows that opening the streets and loosening the brutal repression it has maintained for twelve years now poses an existential threat. El-Sisi knows that escaping the trap may well mean political suicide.

Published opinions reflect the views of its authors, not necessarily those of Al Manassa.