Cheers, comrade! To Ziad Rahbani, the ordinary man in pajamas

We all seek recognition—regardless of our line of work. But that yearning becomes more acute when the work is creative. Not everyone aspires to fame, accolades, or wealth and influence. Still, somewhere within us lies a quiet hope: that someone, somewhere, will recognize our talent, will affirm that what we’ve made carries a mark of originality.

Yet this recognition rarely comes free. For those who are gifted, those whose creativity sets them apart, it comes tethered to conditions. It must be bestowed by those considered equals, or better yet, by those above us. Only they, it seems, are deemed worthy of offering validation that truly matters.

I don’t know whether Ziad Rahbani ever spoke openly—true to his famously candid nature—about this yearning for recognition. Still, it might have been a source of turmoil. We can’t presume to know what stirred inside someone who has passed. Still, for many of his admirers—those who call themselves “Ziadists”—the image of Fairuz’s son, heir to the Rahbani legacy, is tinged with exhaustion, melancholy, or the ritual of drinking to fend off time. These impressions, while never clearly explained, became part of the mythology—shaped as much by love as gossip.

If recognition was complicated or troublesome, it might be because Ziad received it early for his songs and music. Giants of his world—his mother, father, and uncle—recognized his teenage compositions. Yet perhaps because they were his family, and because he was known for his critical, questioning nature—uncomfortable with easy reassurance—this recognition wasn’t enough.

The utterly ordinary revolutionary

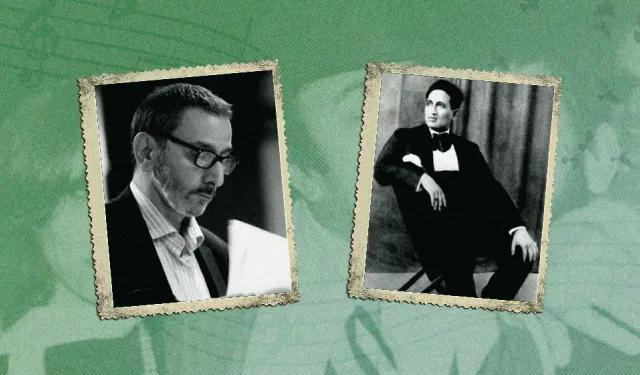

Among the many images of Ziad, one stands out: a photo taken years ago, showing him at home in his pajamas—not onstage, not in costume. Just a simple photo, yet one of countless small things that made tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands of people feel unusually close to him. It’s the sense that we could knock on his Beirut door, and he might open it, invite us in with effortless ease, start talking—or arguing—without even thinking to change out of his pajamas.

He was the father we remember in his pajamas, even in death—sitting comfortably in the living room, warm and unpretentious, entirely at ease. Or the older brother, or the closest friend—the true companion, who pulls you aside to talk, never bothering to fix his appearance.

It’s as if we’ve all visited Ziad’s home, and he surely knew that this ordinariness, this simplicity, and this quiet alignment with us were part of what made him an artistic, human, and revolutionary icon—alongside the artistic value of his work.

Few things are harder than rebelling against one’s family—especially when that family is powerful, respected, and successful in the same field one chooses for their own creativity. It’s not just rebellion against tradition or aesthetic norms. It’s the refusal to lean on inherited capital, to walk alone, to abandon the legacy and its comforts, to risk everything anew each day. It’s daring to critique, to mock, even oneself—tearing down the myth, bringing it down to earth, making it mundane and even soiled.

Such figures are exceedingly rare, particularly in the arts, where success often builds on previous success and translates into enormous material gain. Ziad was one of those rare figures. And because they are so few, they symbolize a profound courage, singularity, and yearning for freedom. Simply because this small group exists, we, who look up to them, give them an iconic dimension that’s inseparable from the purity of detachment from what’s comfortable and what the family has achieved.

Despite these terms –“iconic” and “purity”– and the mysticism and sanctity they carry, which Ziad himself rejected, the mere existence of a few like him offers hope for a different world. A world that is more free and just, that doesn’t rely on inheritance or capital, and doesn’t rely on accumulation.

Some love Ziad only for his work with Fairuz. But “Ziadists” are much more diverse. They love Ziad not only as a composer, but also as a writer, playwright, broadcaster, performer, incisive political satirist, and political revolutionary.

It’s no surprise that his biggest following comes from the spectrum of Arab leftists and progressives—those eager to shatter all taboos. His work made no secret of its commitment to revolution and liberation. To separate his music from its political content would be to reduce it to lifeless form, floating in a void.

Ziad’s rebellion against his family of musical and theatrical giants—and his conscious political and intellectual commitment to the poor, the marginalized, and the “infidels,” as one of his most famous songs puts it—is at the heart of his legacy. It reflects a kind of courage and revolutionary spirit we rarely encounter.

This conscious choice may have naturally led him to embody the image of the romantic revolutionary artist—clinging to the dream no matter the cost. And when the age of revolutions faded, he didn’t stop at challenging his family. He went on to question the walls of class, sect, nationalism, and tradition—even the sanctity of the leftist project he identified with. Ziad criticized it harshly, stripping it of holiness, remaining loyal only to the concept of absolute freedom.

Not the selfish or individualistic kind of freedom. Not merely the freedom to innovate or break artistic molds. But a freedom rooted in justice—a belief that those who’ve never had freedom deserve it most. That they have a right to build a new world, shaped by liberated individuals. This was the world Ziad believed in, sang for, and tried to illuminate from the stage. And sometimes, in the heart of the Lebanese Civil War, he dared to voice this dream in his radio monologues on Sawt Al-Shaab/the voice of the people.

Pajamas in the living room

This universal struggle for recognition—especially acute in Ziad’s case—leads me to imagine him composing new melodies, new plays, new monologues. This, even after he had secured a place in the canon, receiving recognition from his family and the greats of music and art throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s—figures who are now gone, one after another.

I picture him creating, waiting for recognition from someone who would never be able to offer it: Sayed Darwish, who died long before. It’s as if Ziad was still speaking to him, still reaching out, still deeply moved by him—not just musically, but in spirit: in devotion to the people, revolution, and rebellion.

But I’m not a musician, nor a theater expert, so I’ll stop here, except to state one sad truth: no one in today’s Arab world can match Ziad Rahbani’s creative stature. No one can grant him that recognition—or deconstruct him so that we might learn from him.

The sole recognition Ziad has received day after day, year after year, and will continue to receive for many years to come, is from his fans, the millions in this vast tribe of ordinary people across the Arab world. They acknowledge him as their comrade, their friend. They look to him not just as an example but, more importantly, as a source of solace, companionship, and the energy to rebel and revolt.

On July 26, many bade farewell to Ziad with one word: rafiq/comrade. Not because they were communists mourning a fellow communist. But because they were saying goodbye to an extraordinary artist—in pajamas—who insisted on being one of them. Who offered them his art as if raising a glass to a comrade in the living room, saying: “Kassak ya rafiqi/cheers, my friend”. In doing so, he shattered the aura of musical sanctity and let each of us see something of ourselves in him—something real, or something we wish existed in us—reflected in the image of Ziad.

From this place of intimacy, we grieve his death—calling him simply Ziad, as we would any true friend. Especially now, in this harsh moment, during the annihilation of the people to whom Ziad devoted his political and artistic life. When our comrade—rebellious, brave, romantic, outspoken, and fearless—dies, we feel the sting of isolation. We feel weaker, across every city and most villages in the Arab world—places he once addressed, even if he never set foot in them. Still, they have only one thing to say in return: Cheers, comrade Ziad.