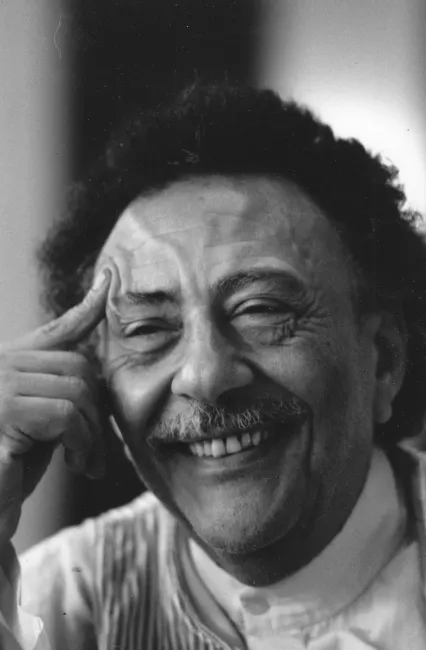

Raouf Mosaad sets out on his final journey, Salam!

Al Manassa mourns the great writer Raouf Mosaad, who departed this world on the evening of Friday, Oct. 17, leaving behind an indelible mark with his writings, his struggle, his rebellion, and his progressive positions in support of truth, justice, and freedom.

Beyond the impact of his published words, Al Manassa will miss our "Top Fan" and number-one reader, who never passed over a story without offering insight, and whose comments were always steeped in experience and knowledge.

We will miss his critiques, his boldness, and his resonant, unyielding voice. Mosaad lived as he wrote—resisting all forms of authority: religious, social, or political.

Walking in the wilderness

Raouf was born in Sudan on March 20, 1937, to a Protestant pastor, where he received his early education before moving to Egypt, where he gravitated towards the progressive communist movement.

It wasn’t long before his fate was sealed: years in prison alongside leftist activists and writers. That inspiring generation of the 1960s, including figures such as Abdel Hakim Qasem, Yehya Mokhtar, and Sonallah Ibrahim, faced the iron fist of the Nasser regime after it turned on them in 1959.

Despite the severity of this experience—and the pain it left in his soul and the marks of torture on his body—those four years in prison constituted a pivotal moment in Mosaad’s life.

Prison was “a key to many sealed and suppressed chambers inside the human soul,” as he later wrote in his novel “Baydat Al‑Naama/The Ostrich Egg”. If it wasn't for prison, he said, he might never have met Sonallah, nor written his literary works, nor seen the world as he saw it. Yet prison set him wandering in the wilderness.

After prison, he could no longer trust the homeland that had shackled his soaring spirit. In an effort to break free, he lived in Iraq, Poland, and Lebanon, but his wandering did not end until he settled in the Netherlands with his third wife and lifelong partner, Anna Marika, who made Amsterdam his home. There, at last, he found a roof, a room, and a bed of his own—and the warmth of a family with two children, Yara and Diederik.

From his pioneering first book, “The Ostrich Egg,” Mosaad never shied from the most difficult or controversial subjects. He wrote with precision and intellectual fearlessness, taking on questions of identity, equality, and freedom in the face of political and religious authoritarianism.

“The Ostrich Egg” hovers between fiction and autobiography. Mosaad described it as an attempt to find himself as a child of a “minority of the minority,” being a Protestant by birth. Estranged from himself, his family, his country—his entire world—he turned that estrangement into art, confronting power, conformity, and fear at once.

This journey through time and place, “The Ostrich Egg,” includes visiting prisons, exposing oppression, torture, and jihadist groups, and delving into the dark rooms of all social classes. With a rebel’s audacity he shattered the three taboos—politics, religion, and sex—even addressing homosexuality within prison. Going beyond mere exposure, the work made a real impact, even if only years later.

“I wrote about same‑sex relations in prison and outside, despite Sonallah’s objection on the grounds that State Security would use what I wrote against the communists,” he wrote in “A Stroll Through Memories,” an article for Al Manassa. “I insisted, although I became more cautious in my writing. Years later, Sonallah would write the novel “Sharaf,” also about same‑sex relations in prison, but among non‑political inmates.”

Mosaad was, in many ways, a pioneer of erotic literature. From “The Ostrich Egg” through “Ithaca” and across his entire oeuvre, in which sex, seduction, and the contemplation of bodies occupy a vast space.

As he said in an interview, Raouf wrote “about sexuality, not about sex.” Through it, he explored intimacy and alienation, the individual and society. Sex, he wrote in “The Ostrich Egg,” “is the thermometer that gives me a reading of society’s inner dynamics. It is not only sexual relations in the direct sense, but bodily contact in all its complexity, including prostitution as a profession for both genders in Egyptian society after the open door policy [under Sadat].”

Peoples' springtime, patriarchs autumn

Raouf exemplified the concerned intellectual and the activist immersed in the causes of his homeland and the struggle of his nation. His flight from a homeland that jailed him without charge, his years roaming between countries, and his eventual settlement in the Netherlands, whose winters he fled for Aswan—never caused him to forget Egypt, or his empathy for its people, especially those who fought for freedom of speech and action.

Few causes escaped his attention. He rejected authoritarianism. He stood with the wronged, the imprisoned, the humiliated, and the accused. He dreamed, as he put it, of “the Egypt we live in our imagination, not the Egypt we deal with every day in reality, from the traffic policeman to the rest of the state’s institutions”—a beautiful Egypt, not one that “frightens us like a monster.”

Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza weighed heavily on him. He who had lived through the siege of Beirut and witnessed, up close, the Palestinian struggle—not as an observer but as a chronicler. He recorded that time in “Sabah Al-Khayr Ya Watan/Good Morning, Homeland”, and later in “Fi Intizar Al-Mukhallis: Rihla ila Al-Ard Al-Muharrama/Waiting for the Savior: A Journey to the Forbidden Land”.

He visited historic Palestine and hoped to see its flag rise over the usurped lands, over a people long—and still—subject to genocide and expulsion. He dreamed of one state shared by both peoples, where Palestinians are citizens of equal standing. Yet that dream remained far, in a world where Israel’s war machine targets children, women, and the elderly.

The author of “Ithaca,” “Mazaj Al-Tamaseeh/The Mood of the Crocodiles”, and “Lama Al-Bahr Yan'as/When the Sea Grows Drowsy” stood with every just struggle that came organically from the people, never one imposed on them.

He dreamed of peoples' spring and an autumn for Arab patriarchs, borrowing the title of Márquez’s “The Autumn of the Patriarch.” “Here we are at the beginning of autumn,” he wrote on Facebook. “The patriarchs may not fall or be exiled to an island, because bringing down patriarchs fortified by mercenary soldiers and politicians is no simple matter! But peoples always surprise us with their ever-renewing spring, which the patriarch tries in vain to bury in cold prisons and damp cells. The patriarchs seize and disappear a handful of people, only for hundreds to rise in their place. It is a magic circle of spring—activists who resemble the mythic phoenix in their rising from the ashes.”

Time to depart

In late July, Mosaad wrote: “Departure has its set hour. We are guests in this world—we enter it naked and crying, and we leave it naked and silent. On my last visit to Egypt I met Sonallah, and we spoke about ‘departure.’ I told him I was ready. He replied, in effect, that when our mission in life is complete, we will leave. He has a sardonic phrase for the time of departure; he calls it ‘the final call.’ … Sonallah, Kamal (El‑Qalash), Nabil, and I have taken from life what it offered us—family, children, grandchildren—and we gave it what we could, to the limit of our ability. We depart in gratitude. We must heed the final call, and depart with dignity, at our time.”

A day later, he added: “Sonallah chose his life and remained true to his choices till the end. Kamal El‑Qalash also chose his life. And I chose mine. But I, will choose my departure—from this life and for whatever may come after it, if there is anything after.”

Two weeks later, his lifelong friend Sonallah Ibrahim died at 88. Raouf followed at the same age two months later.

His family announced that he passed peacefully in his sleep in an Amsterdam hospital, surrounded by those he loved: “Dear family, friends, and loved ones, We are sorry to announce the loss of our father, husband, and friend. A life that touched many hearts in meaningful ways. He died in his sleep due to heart failure, surrounded by his loved ones. We remember him in countless small moments, the smile, the words, the stories. In those memories, Raouf lives on not only as someone who was, but as someone who remains in our hearts. He will be cremated in the presence of his family and close friends.”

The family also shared the words he posted on his last birthday—his 88th—this past March, his parting note to the world:

Nature gave me freedom of movement,

but she also struck:

in my sight, so that now I see only dim shadows,

and in my heart.

Yet I am grateful to her –

she left me my mind

and my beloved follies.

She granted me my wife,

the mother of my children,

and through my dear Yara, two wonderful grandchildren.

My wife gave me a son: kind, gentle, and helpful.

She is my support, my warmth, my home.

A few friends still haven’t grown weary of me

in this long journey of life,

filled with travel, joy, and stories.

I have held on to a few virtues:

honesty, openness, and respect

for those who think differently. And when, like my parents,

I approach the far shore of the river,

I will be able to say:

I have not polluted the river,

wronged the widow,

nor violated the rights of the orphan.

One shall walk the path written for them,

and no soul is burdened beyond its limits.

Raouf Mosaad Basta

Published opinions reflect the views of its authors, not necessarily those of Al Manassa.