Ancient Khemites: Museums and the making of modern Egyptian identity

In his 2007 book “Contested Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity,” scholar and researcher Elliott Colla explores the competing ideologies and narratives surrounding the history and antiquities of ancient Egypt, from the medieval to the modern eras.

These narratives were constructed by local, regional, and international actors, each expressing their distinct identity, role, and sphere of influence within the development and perception of Egyptology. Long thought extinct, the civilization seemed to come alive again, speaking for itself through the decipherment of hieroglyphics and the later discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Across the historical documents and eras that Colla examines in his book, Egypt’s antiquities emerge as both a stage and a mirror. They reflected the ways in which various powers conceived of their relationship to the past and sought to justify their own existence, actions, and civilizational position, whether colonial, progressive, national, or religious.

What Colla terms the “narrative of colonial enlightenment” emerged in the 18th century from a European desire to claim kinship with ancient Egyptian civilization—an imagined lineage linking Europe’s modern progress to its supposed origins in Egypt. Under this logic, Egyptian antiquities became the legitimate property of those deemed worthy to own it. This worldview paved the way for modern colonial plunder, coinciding with a growing fascination with archaeological research. From the two, the earliest forms of the “museum” were born.

The Sculpture Gallery and the Egyptian-European Museum

What Colla calls the “ideology of preservation” was a crucial element in the formation of 19th-century museums. Sculpture galleries were designed to house artifacts in order to protect them from loss or destruction if left in their original locations, where they were unrecognized in value by those around them and vulnerable to decay.

Within this framework, European explorers and archaeologists, such as Champollion, Karl Richard Lepsius, Gaston Maspero, and Howard Carter, produced narratives claiming that seizing Egyptian antiquities and transferring them to Paris, London, and Berlin was an act of “rescue.”

Yet, in reality, the so-called “rescue” amounted to little more than violations and thefts, beginning with the seizure of the Rosetta Stone by Britain in 1802 and the transport of the head of Amenhotep III (detached from one of the Colossi of Memnon) by the Italian Giovanni Belzoni in a semi-official operation under British Consul Henry Salt in 1818.

However, the Western archaeological presence in Egypt evolved with the decipherment of hieroglyphs and the establishment of Egyptology as a discipline. The ideology of preserving and possessing “material artifacts” expanded into building knowledge about all aspects of the civilization they belonged to, from social life and centralized authority to religion, moral philosophy, engineering, mummification, agriculture, and the evolution of science and art.

From this point, the relationship between site, landscape, and antiquity acquired a new coherence, and competition intensified among Western archaeologists for dominance over Egyptology, first inside Egypt, then beyond it. This coincided with Mohammed Ali Pasha’s growing awareness of the value of ancient Egyptian civilization in Western eyes, and of the promise archaeological discoveries held in enhancing that value.

In 1835, Mohammed Ali issued his first decree regulating the management of Egyptian antiquities. Having noted “the importance that the Europeans attach to the ancient monuments and the advantages that the study of antiquity brings them,” the ordinance’s three articles strictly prohibited the export of antiquities, ordered that all artifacts, as well as those discovered in future excavations be housed in a single location in Cairo, and forbade the destruction of ancient monuments in Upper Egypt and their preservation everywhere.

A symbol of state sovereignty

This decree helped establish the principle that ancient Egyptian antiquities were the property of Egypt and led to the creation of Egypt’s first museum, known as the Antiqakhana or House for the Preservation of Antiquities, in Cairo’s El-Ezbekeya district, overseen by Egyptian renaissance thinker, Rifa‘a Al-Tahtawi. The museum, however, ultimately struggled to organize the collection and cataloging of artifacts and failed to curb widespread theft, which increasingly involved Egyptians themselves.

Under Saeed Pasha, French archaeologist Auguste Mariette was appointed to oversee the second Antiqakhana—the Boulaq Museum, founded in 1863. Mariette set out to gather all of Egypt’s dispersed artifacts into a single museum, filling incomplete collections and recovering ancient jewelry and coins from private collectors, sometimes at his own expense. He once paid 4,000 francs to buy back papyrus scrolls held by the French consul at the time.

The establishment of the Egyptian Antiquities Service reframed the institution of the museum as a symbol of state authority over Egypt’s national heritage, yet the service itself remained under foreign control. Egyptians were confined to marginal roles and deemed unqualified for archaeological research. Ultimately, the Boulaq Museum emerged as tangible embodiment of the notion of a continuity between ancient and modern Egyptians, as Mariette himself explained:

“The Museum of Cairo is not only intended for European travelers. It is the Viceroy’s intention that it should be above all, accessible to the natives to whom the museum is entrusted in order to teach them the history of their country. I would not be maligning the civilization introduced to the banks of the Nile by the dynasty of Mohammed Ali if I were to assert that Egypt is still too young in the new life which she has just received to have a public easily impressed in matters of archaeology and art. Not long ago, Egypt destroyed its monuments; today it respects them; tomorrow it shall love them.”[1]

Al-Tahtawi and Ali Mubarak: The harmonizing narrative of Ancient Egypt

Beginning in 1820 and continuing throughout the first half of the 19th century, Muhammed Ali sent various missions of Egyptian students abroad to Europe to be exposed to its intellectual milieu.

Students returning from these missions eventually assumed administrative and intellectual roles in Egypt during the second half of the century. A number of them helped shape a new educational approach that introduced ancient Egypt into the classroom, aiming to cultivate a modern historical consciousness among students. This approach marked the beginnings of what Colla calls the “national enlightenment narrative,” which inevitably clashed with the dominant historical narrative of the monotheistic religions.

The biblical story of the Exodus cast ancient Egypt as the object of divine wrath—a narrative later echoed in Christianity and Islam, portraying its people as “idolaters” punished by divine will. As Colla notes, When Muslims entered Egypt, they exhibited a deep interest in its ancient monuments—most notably the three pyramids, whose remarkable survival over the centuries puzzled historians and geographers like Al-Idrisi, Abdel Latif Al-Baghdadi, and Jalal Al-Din Al-Suyuti. In their accounts, they described the pyramids as “idols,” “ruins” of a vanished civilization offering lessons to learn, and “wonders” in terms of their construction and endurance.

Since the time of Mohammed Ali, Egypt’s rulers and elite came to realize that the immense cultural value of ancient Egypt, which Westerners had long admired, could serve Egypt’s own project of modernization. This prompted Rifa‘a Al-Tahtawi and Ali Mubarak to construct a narrative that reconciled Islamic perspectives with the emerging discipline of Egyptology with the aim of building a broader base of supporters of Egypt’s rightful claim to its ancient heritage, in light of ongoing attempts to smuggle and seize neglected artifacts.

The ruling elites themselves had turned to using antiquities as a store of value, adding some to their private collections, and gifting them to foreign rulers and elites for various purposes and interests.

Colla notes the gradual shift in the perspectives of Rifa‘a Al-Tahtawi and later Ali Mubarak, as their increasing involvement with Westerners led them to link the historical legacy of ancient Egyptian civilization with the concept of “nation,” which unites the “sons of Egypt” or the “people of Egypt” (the terms used at the time) in a shared and enduring experience of life. This perspective was incorporated into modern curricula through Mubarak’s expansion of schools and his efforts to highlight Egypt’s ancient sites in his encyclopedia, “Al-Khitat Al-Tawfiqiyya.”

As part of shaping his position of cultural leadership, Al-Tahtawi developed a new narrative envisioning Egypt’s path to modernity by linking ancient and contemporary Egyptians through affirming the conceptual relationship between society and land within the “Egyptian homeland.” This vision is clearly reflected in his work “Manahij Al-Albab Al-Misriya fi Mabahij Al-Adab al-‘Asriya” (The Roads of Egyptian Hearts in the Joys of Contemporary Arts).

The impact of this historical turning point is also evident in Al-Tahtawi’s approach to historiography. He took inspiration from Ibn Khaldun’s “Muqaddimah” (Prolegomena), interpreting world events as having temporal, rather than divine, causes. He began dividing the study of history into two parts: the history of world events as recorded in the sacred texts of monotheistic religions, and the history of the world as documented in reliable textual sources, regardless of their origin.

Guided by this approach, Al-Tahtawi divided Egyptian history—from ancient times to the present—into two main periods: the first, pre-Islamic, which he further subdivided into the period of paganism followed by the spread of Christianity; and the second, post-Islamic.

While the new educational curricula aimed to fabricate a connection between the development of belief in ancient Egypt—especially during Akhenaten’s reign—and the evolution of the Abrahamic religions, particularly Islam, it also set the precedent that Egypt’s pre-Islamic ethical traditions and civilizational achievements were independent fields of study in their own right. This approach highlighted ancient Egyptian society’s sophistication and remarkable accomplishments in law, justice, and science.

Drawing on Ibn Khaldun’s theory of civilizational cycles of decline and renewal, Al-Tahtawi applied the same pattern to Egypt’s hoped-for “renaissance” under Muhammad Ali, portraying ancient Egypt as “an image of the glory to which the present must aspire,” as Colla puts it.

Al-Tahtawi followed this thread to link Egypt’s decline and the loss of its “virtues and prosperity” to the “historical reality” of successive waves of foreign rule and occupation. According to this vision, Al-Tahtawi transformed ancient Egypt into the beginning of an ongoing trajectory from the “origin” of history. He rejected the notion that Egypt’s bleak present was predetermined fate and reconceptualized it as a moment charged with the potential of reviving past greatness.

Colla writes that the works of Al-Tahtawi and Mubarak produced “a new history that retains religious narratives about the past while adding to them information garnered from Egyptological discoveries about Pharaonic antiquity; new concepts of place, space and community that subtly uncouple Egypt from the Islamic and regional traditions of cultural identity; the image of a bounded territory inhabited by a single people sharing a unified transhistorical experience…These concepts and themes, made concrete in the material of antiquities and housed in the single institution of the museum, came to pose a tangible reality, one immediate as it was timeless. This new perspective on Pharaonic civilization contributed greatly to its rhetorical potential and explains why, many decades later, it would play a prominent role in the nationalist movement of the 1920s.”

Beyond the museum

During the reign of Khedive Ismail (r. 1863–1879), Ali Mubarak commissioned the German Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch to establish the School of the Ancient Egyptian Language to train native Egyptologists. Among its graduates were Ahmed Kamal and Ahmed Naguib, both of whom worked in the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

In 1894, Naguib published “Al‑Athar Al‑Jalil li‑Qudamaa Wadi Al‑Nil ” (The Grand Monuments of the Ancients in the Nile Valley), which adopts a more assertive tone in urging Egyptians to reconnect with their ancient heritage. His words guided a generation of thinkers known as the Nahda (renaissance) intellectuals, who berated Egyptians for their ignorance of their country’s antiquities and urged them to reconnect with these sites, including by visiting Upper Egypt:

“The chronicles of ancient Egypt uplift the ambitions of nations far and wide. Scholars of every land travel here, and the greatest statesmen and dignitaries undertake long journeys to behold these jewels and study their inscriptions. They teach the history of Egypt to their children, and some of their youth learn its ancient script—though it lies nearer to us than the vein in our necks. Are we not then the most entitled and most obliged to know it, we who are the people of this land?”

In 1912, Ahmed Lutfi Al-Sayed published an article titled “Ancient Monuments,” which, alongside encouraging domestic tourism to ancient sites—both Pharaonic and Arab—also introduces the concept of tourism abroad, understood as involving trade, information gathering, foreign publicity, and “colonial” engagement.

“The Egyptians were not a people of idleness, they were not opposed to travel, nor satisfied with whatever resources were at hand. They were actually a hardworking, colonizing nation, whose colonialism was carried out using the most advanced European methods of today. Their envoys traveled from Egypt to distant regions of Africa, not only for trade, but to spread knowledge of Egypt, its people, their language and faith, describing their property and the wealth of their land, so that when Egyptian armies advanced, these distant regions became accessible, thanks to the information provided by these travelers.”

He went on to describe Egyptians as “the most tolerant of colonizing nations,” imposing no religion, customs, or governance except recognition of Egyptian sovereignty and protection from foreign aggression and support in Egypt’s wars.

The article marked the beginning of a phase in which ancient Egyptian civilization became central to imagining modern national sovereignty—countering those “who doubt Egypt’s natural aptitude for independence.” Al-Sayed celebrated Egypt’s ancient kings, before whom “envoys of other nations came bowing, rubbing their noses in the dust, silenced by awe of his majesty,” and portrayed Egypt’s political system as one in which “the king was not everything; the nobles and ministers often had great influence in reform and governance.”

Alongside the museum, ancient Egypt—through the writings of Al-Tahtawi, Mubarak, Ahmed Naguib, and Ahmed Lutfi Al-Sayed—became a means to transform the “miserable present” into a temporary and reversible condition, where reclaiming the grandeur of the ancient civilization embodied an aspiration: “Whatever was possible in the universe in the past is not impossible today.”

By re-entering modern Egyptian life after centuries of silence, and through its enduring grandeur, ancient Egyptian civilization secured its lasting place within the fabric of modern national identity—with all its tensions, contradictions, and polarizations that would erupt more vividly after the 1919 Revolution, and continue to this day.

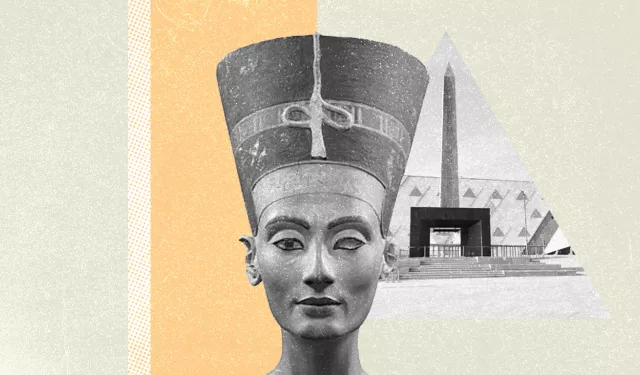

With the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum, which was built by Egyptians, and whose conservation and research labs are filled with generations of their own archaeologists, we have the opportunity, after two centuries, to begin the era of the “Citizens’ Museum,” “Society’s Museum,” and the “World’s Museum”—beyond fundamentalist identity conflicts, and on an equal footing within the global knowledge society.

[1] August Mariette, Notice des principaux monuments exposés dans les galeries provisoires du Musée d’Antiquités Égyptiennes, p. 127.