Interview| Monica Hanna: Confronting Afrocentrism through research, not racism

At its core the disagreement with me is political

For years, Egypt has been the stage for a fierce and multifaceted debate over the true origins and identity of its ancient civilization. This argument is far from settled—it’s a heated battleground where history, race, culture, and politics collide. At stake is not just the past but the future: how Egypt sees itself, how it relates to its African neighbors, and the role that science and ideology each play in defining national identity.

Movements like the Children of Kemet champion an Egyptian identity rooted in racial purity, while many scholars insist on a more complex narrative—one that recognizes the interconnected cultural and genetic history along the Nile Valley without succumbing to politicized revisionism. On social media and academic forums alike, these rival visions have ignited passionate, often bitter clashes that go beyond archaeology to touch on deeply held views about race, heritage, and belonging.

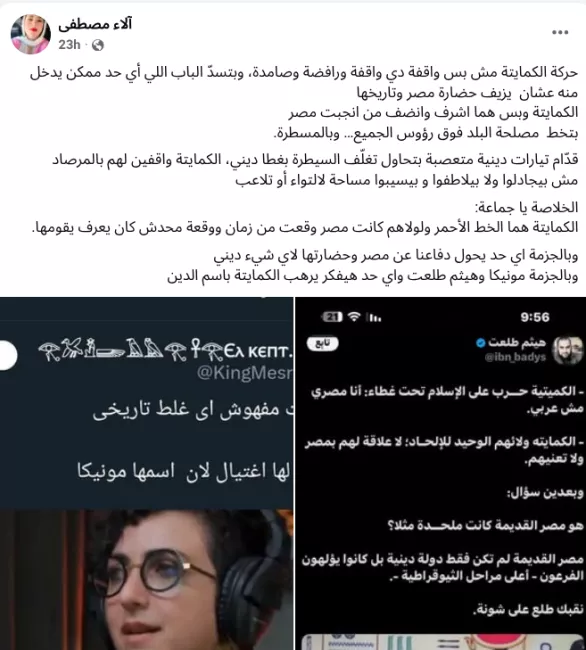

Amid this escalating controversy, a prominent Egyptian Egyptologist and archaeologist has found herself at the heart of a social media storm of attacks and smears.

Monica Hanna has built her public presence on defending Egyptian antiquities and heritage and on criticizing official policies for managing the antiquities portfolio, from her comments on how the Grand Egyptian Museum operates to her public criticism of prominent figures in the sector, foremost among them archaeologist, Egyptologist, and former Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, Zahi Hawass.

Today she has become the target of an online campaign accusing her of casting doubt on “the origins of Egyptians” and of supporting “Afrocentrism.”

In contrast, Hanna, an assistant professor of archaeology and cultural heritage and dean of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at the American University in Cairo, sees what she is facing as the direct result of her refusal to politicize science and of her opposition to what she calls “online troll farms” linked to the so-called Children of Kemet movement, whose members embrace an Egyptian nationalist ideology and believe in the purity of the Egyptian race.

In her conversation with Al Manassa, Hanna draws a line between criticism, which she does not reject in itself, and what she sees as a coordinated campaign now directed at her.

She traces what is happening to the combination of her public visibility and her positions. “I speak from a scientific perspective, not an ideological one. Many people want you to pick a camp, right or left, and no one is willing to accept that you might have an independent opinion.”

Genes and migrations

One of the most widespread accusations against Hanna concerns her comments about “Ethiopian genes” and their relationship to Egyptians. She sees this as a clear example of how some are manipulating scientific discourse and turning it into a weapon in a war over identity.

“I said that in the eras of migrations associated with what are known as haplogroups, most of the inhabitants of the Nile Valley shared common genes, not just in Egypt but also in North African countries and the Near East. We are talking about a long history of migrations along the Nile Valley, not about claiming that Egyptians ‘originate’ from Ethiopia, as some are promoting.”

To simplify this for non-specialist readers, Hanna places ancient Egyptian civilization in its broader geographic and historical context. “The relationship between ancient Egyptian civilization and African migrations is a complex, interactive relationship that centered mainly on the axis of the Nile Valley. Egypt, with its unique geographic position, was a point of genetic and cultural convergence between North Africa and the Near East. Archaeological and climatic evidence indicates that the migrations caused by desertification in prehistoric periods contributed to the settlement of the Nile Valley and to the development of Egyptian civilization.”

She adds that Nubia represented “Egypt’s strongest link with Africa,” and that the influence was mutual, “reaching its peak when the Nubian Twenty-Fifth Dynasty ruled all of Egypt.” Yet she explains that this influence remained constrained by geography. “The limits of that influence were also tied to the nature of the land. Deserts and long distances created natural barriers that reduced direct contact between Egypt and the regions of sub-Saharan and central West Africa. The greatest influence was always associated with the Nile Valley north of the Nile cataracts.”

This scholarly debate about migrations and genes has turned into ammunition for social and political confrontation, which Hanna links to “young people’s reluctance to engage in public political life.” She believes many young people “are absorbed in a sterile argument to prove their ownership of a civilization that already belongs to them, as part of a war over identities, instead of engaging with the present to build a real future for themselves.”

“The dazzling heritage and past should enrich the present, not turn into a tool for creating a sterile societal conflict over identity,” she said. “I imagined that a movement like the Kemites, for example, would produce candidates for the Egyptian parliament whose agenda would be protecting heritage and recovering our looted antiquities. But that did not happen.”

Hanna poses what she considers a fundamental question.“Can these young people refute the fake science of the Afrocentrists or others with hateful racist rhetoric? The reality is that we do not see these movements on the front lines against illicit excavations, against negligence at archaeological sites, against erasing or demolishing antiquities, or against encroachments on archaeological areas.”

Rejecting both centrisms

Although she was among the first to criticize Netflix’s portrayal of Cleopatra as an “Afrocentric” icon, Hanna now finds herself accused of supporting this very current.

She sees this accusation as part of constructing a completely inverted image of her. “The main reason for this accusation is my rejection of racism and my insistence on acknowledging the African tributaries of ancient Egypt, just as I recognize its Mediterranean and North African tributaries. Unfortunately, many of the views of today’s nationalist current mirror the Eurocentric current in their rejection of Afrocentrism; they just invert it. From my point of view, we must reject both centrisms.”

Emotional posturing, she argues, is ineffective in this context. “We need strong academic publishing and sound scholarly writing, not tit-for-tat on social media and trading insults,” the Egyptian academic said.

Afrocentrism has spread globally because it is directly linked, Hanna explains, to the American context, “to what is called American identity politics, and to decades of theft of African heritage that needs to be restored. This cultural void created by looting is something African Americans are trying to fill through this pseudo-science.”

Hanna acknowledges that “there is a real wound,” but she believes that trying to treat it through extreme narratives does not serve historical truth.

The award-winning researcher in archaeology and heritage preservation draws a clear line between the “natural African tributaries” of Egyptian civilization and “attempts to claim the civilization” for contemporary agendas such as Afrocentrism.

“The distinction,” she said, “rests on the difference between scientific method and political motive. Natural tributaries refer to mutual cultural interaction that is historically and geographically documented and rests on solid academic evidence from archaeology and texts. This evidence confirms that ancient Egyptian civilization arose and developed in an African environment and interacted vibrantly with its surroundings, especially Nubia (the Upper Nile Valley). But it does not exclude other influences; instead, it sees them as part of a complex cultural matrix.”

By contrast, attempts to claim the civilization for ideological purposes, whether from Afrocentrism or elsewhere, “seek to reduce the origin of ancient Egyptians to a single group and to erase other aspects, relying on biased cherry-picking of evidence and on modern racial concepts such as skin color to serve current political or social agendas related to ownership of heritage and asserting identity, instead of pursuing a historical understanding of how civilization developed.”

For that reason, she stresses that “grounding ancient Egyptian culture as a source of identity, rather than race or genetic similarity, is a far stronger step, because it closes the door to this kind of one-upmanship.”

Egypt as culture

The campaign against Hanna began three years ago, when she published an article titled “Egypt as culture, not race,” which has become the weapon most often used against her.

“I wrote that article as a direct response to the controversy around the Cleopatra docudrama on Netflix and the debates about race that followed,” she said in her defense.

The 2023 Netflix docudrama “Queen Cleopatra” ignited a firestorm in Egypt by portraying Cleopatra as a Black African woman. Egyptians, from officials to scholars, condemned the depiction as an affront to their history and identity, accusing Netflix of “blackwashing” a pivotal figure. The Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities publicly rejected the portrayal, affirming Cleopatra’s Macedonian Greek heritage. The dispute grew so intense that legal action was even pursued to block Netflix’s service in Egypt. Netflix defended the casting as a “creative choice,” emphasizing the region’s multicultural past, but the backlash exposed deeper tensions about race, heritage, and politics.

“Focusing on the skin color or race of ancient Egyptians is the wrong way to approach Egyptian identity,” she said. “Ancient Egyptian art itself depicts a wide range of skin tones and features, which indicates that diversity was always present. Prominent historical figures were never defined in our heritage by their color, but by their contributions in architecture, art, civilization and language.”

She added, “The phrase ‘Egypt is culture, not race’ was a conclusion: that Egyptian identity is layered and multifaceted, built over thousands of years, and defined by shared cultural practices, traditions and language, not by a single fixed racial category.”

Recycling that headline, Hanna believes, has a political dimension. “I think there are parties that have an interest in stoking conflict over identity in our region because it helps feed a broader conflict across the whole region.”

Hanna sees the very concept of race as “one of the most controversial concepts and, at its core, a relatively modern social construct rather than a fixed biological reality.”

Historically, the term did not take on its modern divisive meaning until the beginning of the era of European colonialism. “In the fifteenth century, the word ‘race’ meant lineage or descent. Then in the eighteenth century it developed into a supposedly scientific tool,” she said.

The Egyptian researcher recalls how thinkers such as Linnaeus used this concept “to divide humans into hierarchical categories (European, Asian, African), linking outward appearance to behavioral and intellectual traits, which provided an ideological justification for colonial domination and slavery.” She notes that genetics has proven that all humans are 99.9% identical, and that genetic diversity within any population imagined to be a single ‘race’ is far greater than the diversity between such populations.

As for the physical traits we use in classification, such as skin color, she describes them as “clinal traits that exist along a continuous spectrum” and are the product of evolutionary adaptation to climate, not discrete categories. She concludes that “there is no such thing as a race gene that unites all members of one group and separates them from another.”

Children of Kemet and racial purity

The “Children of Kemet” groups are among Hanna’s loudest critics, something she traces back to her “rejection of the ideological framing of ancient Egypt that they promote. Most of their information is drawn from Egyptomania sources and from certain pseudo-scholarly currents in Egyptology.”

When asked whether discourses that celebrate ‘the purity of the Egyptian race’ carry fascist or racist tendencies, she answers immediately: “Without a doubt.”

The attacks on Hanna are not limited to accusations about identity and race; they extend to attempts to label her politically. Some describe her as “leftist,” while others accuse her of being “backed by the West.” She responds sarcastically: “Honestly, this whole thing reminds me of a delightful film called ‘Fawzia the Bourgeoise,’ directed by Ibrahim El-Shqanqari. I honestly don’t understand how talking about science is classified as leftist talk.”

“My refusal to endorse extreme ideological rhetoric is instantly translated into me being leftist,” she said. “At the same time, I reject extreme leftist positions that belittle Egyptian civilization or ignore the need to respond to Eurocentric claims, and I’ve written more than once in that direction.”

She added, “At its core the disagreement with me is political. Because I refuse to accept the interference of ideology in science, and because I confront this current and describe precisely its racist practices and its adoption of toxic ideas about Egyptian heritage, all aimed at undermining social peace in Egypt. That is what causes the problem.”

Hanna sees herself as “open to the Western world by virtue of my education, my marriage and daily interaction, but at heart I am a woman from Upper Egypt because of my family and because most of my work has been in Upper Egypt. My father’s grandmother, her name was Sediqa, from Abu Qurqas in Minya, and she was the mayor’s wife. She used to keep a pistol loaded under the pillow. Maybe that’s why I inherited some of the strong-women heritage from her, from my grandmother and from my mother.”

From that background, Hanna looks at Egypt today. “I see an Egypt that is completely different from the racist rhetoric of the Kemet committees. The real Egypt has a culture rooted in geography, history, and heritage and does not need empty one-upmanship. Ancient Egypt is still alive inside people, embodied in a powerful intangible heritage.”