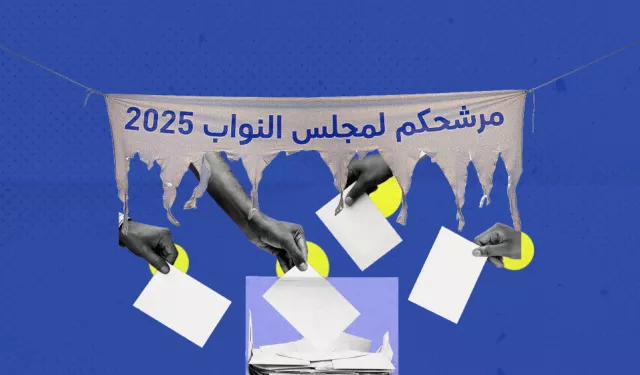

Parliamentary elections with a local-council flavor

“No, we’re not going to talk about prices, because those prices are the state’s to handle, and they’re not in our hands.”

That was how Helwan candidate Shaimaa Abdel Hadi responded to a woman who stopped her during a campaign walkabout, asking what she could do to bring down the cost of basic goods.

This wasn’t a scene from a local council race. It unfolded in the midst of the current campaign for the House of Representatives.

Yet Abdel Hadi, an independent candidate, frames parliament’s mission in terms of upgrading schools, improving health services, and helping reduce unemployment. As for rising prices, higher electricity bills, or regulating rents, she casts those as issues belonging to “the state,” outside parliament’s remit—even as she presents herself as someone capable of easing the daily burdens facing her constituents.

She’s not alone in that positioning. Other candidates have taken the same tack, including former MP Elhami Agina, now running in Dakahliya on the Homeland Defenders Party ticket. At one campaign rally, he told supporters that voters no longer expect MPs to improve education or secure better hospital services.

MPs promising services in the lead

These moments capture the mood of the campaign and help set the backdrop for the individual-seat contests now underway.

Talk of legislative reform is largely missing among independents and pro-government party candidates, who dominate the field. Instead, they emphasize services, usually in broad terms and often without concrete commitments.

Party press conferences announcing campaign platforms have barely made a ripple. Observers attribute that to the absence of real competition and to independents’ dependence on what they can provide at the local level.

With political and partisan rivalry muted, this service-oriented approach keeps candidates in a “safe zone,” steering clear of criticism of government policy or anything that might invite legal or security repercussions.

Pro-government parties control the National List for Egypt, which has already secured half the seats in parliament. Rival lists were pushed out of the race. The first phase of voting took place in 14 governorates at the start of the month, with the second scheduled for Nov. 24–25.

While people look for someone to confront the government over soaring prices, parliament is widely criticized as little more than a channel for government bills—a perception shaped by the last two chambers.

Programs on paper

In theory, election platforms are supposed to anchor campaigns. Parties on the National List have indeed released platforms laying out broad legislative and economic priorities.

Nation’s Future Party secretary-general MP Ahmed Abdel Gawad described them as practical responses to economic challenges, touching on health, education, and infrastructure.

Some platforms center on national and internal security and social cohesion under the banner of protecting the homeland. Others list draft laws they say they would propose to develop industrial, health, and education sectors.

But these platforms have not reached voters through street campaigns.

Every day, Shahira Gomaa, a woman in her fifties, walks past dozens of campaign banners near her home in Basateen, in southern Cairo.

She says she can’t tell which party any candidate represents and hasn’t seen a single platform. All she really knows about the race, she told Al Manassa, is that it’s “a race between the parties’ candidates.”

Pickup trucks roll through the streets carrying candidates’ photos, blaring out their names, and urging voters to support “the true local, man of services.”

“Nobody knows these candidates except their own people,” adds Gomaa. “Even the old faces who’ve been running since the Mubarak era, like Heshmat Abu Hagar, only show up around this time.”

Political sociology professor Said Sadek traces low turnout to a stagnant political landscape, worsening economic conditions, and a prevailing sense that candidates are unable to meaningfully improve people’s lives.

“The electoral scene in 2025 reflects where politics has ended up over the past 10 years,” he told Al Manassa. Pro-government parties, he said, hold the majority and operate with a single agenda: backing the president and his government. “Voters look around at election time and see posters for men in suits and ties, with no charisma and no platforms that address their needs.”

Sadek argues that the platforms announced by pro-government parties bear little resemblance to how they actually conduct themselves in parliament. He points to the last two chambers’ unwavering support for government bills—including contentious measures such as the Criminal Procedures Code and amendments to the old rent law. He also notes their reluctance to use oversight tools to hold ministers or the government to account, a pattern that he says has only deepened public apathy toward the current elections.

Opposition parties have put forward legislative agendas that include many draft laws—some of which never advanced in the last two parliaments—but their messages have barely registered this cycle, overshadowed by candidates’ promises of district-level services.

Limited attempts

Mohamed Abou El-Diyar, a leading figure in the still-forming Hope Current Party, described the obstacles opposition candidates face in trying to reach voters. He told Al Manassa that they had hoped to hold marches in their constituencies, but security agencies restricted them to indoor rallies instead.

He said the elections unfolded exactly as the regime intended, beginning with its insistence on a closed-list system that effectively shut down competition by favoring pro-government parties and denying the opposition meaningful representation. He also pointed to the exclusion of influential former MPs and the pervasive role of political money throughout the process.

For Ahmed Abdel Rabbo, the Egyptian Social Democratic Party candidate in Tanta, “an election program on its own is not enough.” Campaigns, he argued, are shaped less by formal platforms than by a candidate’s ability to anchor their message in core voter concerns—pensions, health insurance—and to bring young people into the fold.

Halem Henish, a researcher at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, sees the individual-seat battles waged by independents as evidence that the opposition could have asserted itself this cycle. But doing so, he said, would have required organization, logistical support, and—above all—the political space to engage in the work of politics: space to promote platforms, to articulate alternatives, and to make a credible case against those in power.

Instead, the race has unfolded as a reminder of how politics in Egypt has narrowed—crowded with candidates, yet offering voters fewer real choices than ever.