The UAE's secret $2.3B bet on Israeli missile tech

On Nov. 17, 2025, Elbit Systems, one of Israel’s “big three” military technology firms, announced a $2.3 billion contract with an unnamed buyer. The deal is among the largest in Israel’s arms trade, eclipsed only by Elbit’s September 2023 agreement with Germany, worth $4.6 billion. For weeks, the buyer remained undisclosed. Then, in mid-December, Intelligence Online revealed that the client was the United Arab Emirates.

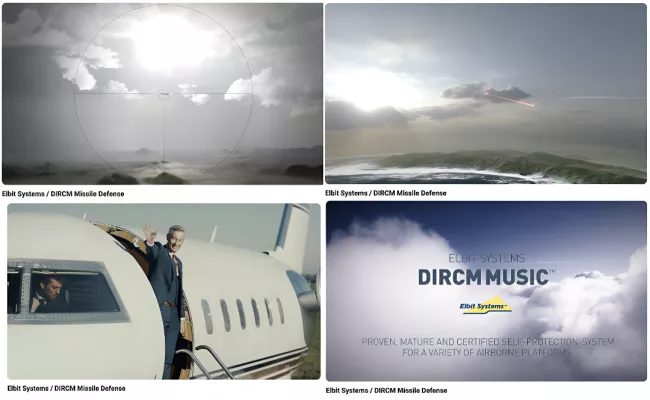

Citing a source familiar with the negotiations, Intelligence Online said the contract would likely expand Elbit’s J-MUSIC Directional Infrared Countermeasures (DIRCM) system—an aircraft-mounted anti-missile suite designed to defeat heat-seeking threats. The system is already deployed across Dutch, German, Brazilian, and Italian fleets, and in Israel it is installed on both military and civilian aircraft, including commercial airliners. The UAE first acquired J-MUSIC technology in January 2022, signing a $53 million deal to equip its Airbus A330 Multi-Role Tanker Transport aircraft.

After the start of the Israeli genocide in Gaza in October 2023, Arab countries publicly called for an arms embargo on Israel under public pressure, with Saudi Arabia announcing a freeze on normalization with Israel talks. However, in February 2025, Elbit Systems secured a major arms deal with Morocco and supplied it with 36 self-propelled artillery systems. While the exact financial value was not publicly disclosed, analysts compare the deal to Morocco’s earlier purchase of 36 French CAESAR howitzers for about 200 million euros ($207 million), suggesting this Israeli deal is of a similar scale.

The UAE’s $2.3 billion arms contract with Elbit Systems is consistent with the expanding Emirati military presence and influence in the Gulf and Sudan. This recent development also brings to light the growing influence of Israel's privatized defense sector through the Middle East and Sahel.

Militarizing civilian skies

The deal emerges amid growing interest among global powers in advanced laser systems for missile defense. Israel plans to deploy its 100-kilowatt laser system by 2026, known as the Iron Beam. The technology was designed by Elbit Systems and Rafael Advanced Defense Systems to swiftly and precisely eliminate missiles, mortar rounds, drones, and other aircraft.

Zionist political leaders and news outlets have praised laser weapons as a low-cost alternative to existing missile and drone deterrence systems, portraying the technology as a breakthrough in Israel’s layered defense architecture.

In parallel, the regional market is on the move. Saudi Arabia recently acquired the Chinese SkyShield missile defense system, using technologies comparable to Elbit’s J-MUSIC DIRCM. Although SkyShield has drawn significant criticism for under-performance in actual conditions, the push toward similar systems suggests that Gulf militaries continue to invest in emerging countermeasure technologies, including lasers, even when real-world results remain contested.

The Emirati government has not issued a public statement on the intended use of J-MUSIC DIRCM. Yet the system’s implementation would likely serve the nation’s economic interests alongside strategic ones. Israel’s flag carrier airlines, including El Al and Arkia, already operate aircrafts equipped with systems from the Elbit MUSIC family, marketed as protection against surface-to-air and heat-seeking missiles.

In the UAE, that security calculus intersects directly with economic survival. With aviation generating an economic output equivalent to 5.3% of their GDP, the state has treated passenger aircraft security as a pillar of national stability. In 2013, the government attained a multi-billion-dollar THAAD anti-missile system from Lockheed Martin, a leading US defense contractor. Lockheed delivered the first system batteries in 2015, and the UAE used it in 2022 to intercept missiles from Houthi forces during the decade-long Saudi-led coalition war on Yemen.

Elbit’s own marketing points to the next step. The versatility of the J-MUSIC DIRCM family suggests potential deployment on Emirati commercial aircraft, alongside expanded use within the country’s military fleet. Elbit’s promotional video underscores the system’s dual uses by emphasizing civilian applications. After the DIRCM successfully diverts an incoming missile, triumphant music plays as one man closes a business deal and another waves from the doorway of a private jet.

For the UAE, implementing Elbit’s anti-missile systems on commercial airliners could enable further expansion of an aviation sector that relies on routes entering or approaching adversarial airspace. If the J-MUSIC DIRCM system moves into civilian infrastructure, the Elbit deal would signal a shift in Emirati aviation security and threat perception, toward the model employed by their close Israeli allies.

Condemning, then contracting

In August 2020, the UAE became the first Gulf state to formally announce its readiness to normalize relations with Israel under the Abraham Accords. The following month, the UAE and Bahrain signed the US-brokered agreement, and Morocco and Kazakhstan later followed suit. Joining the Abraham Accords came with familiar promises of technological innovation and expanded trade, framed as a new regional future anchored in cooperation rather than confrontation.

That public framing fractured after Oct. 7, 2023. Popular Arab discontent with the Abraham Accords reached a tipping point, forcing some signatory governments to manage public opinion in accordance with national interests. While normalization remained formally intact, the political cost of overt alignment with Israel increased sharply across the region.

Saudi Arabia and Qatar responded differently. During Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s widely publicized November 2025 meeting in Washington, the Saudi leader signaled openness to joining the Abraham Accords, but conditioned such a move on the establishment of an independent Palestinian state. Qatar, which has positioned itself as a mediator between Israeli and Palestinian leaders, continued to oppose normalization with Israel specifically under the auspices of the Abraham Accords.

The UAE, however, charted a more explicit course. In public forums, Emirati leaders condemned Israel’s decision to occupy Gaza and continue the annexation of the West Bank. Yet behind closed doors, verbal disapproval of the genocide in Gaza and colonial expansion in the West Bank did not hinder strengthened business partnerships.

This divergence reflects broader differences in how Gulf states pursue military expansion. Islam Khatib, a doctoral candidate at LSE focusing on the intersection of surveillance, knowledge production, and global tech infrastructures, writes that although Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Qatar all invest heavily in Western military infrastructure, Abu Dhabi is considerably less concerned with concealing its relationship with Israel.

Riyadh, she argues, seeks to launder “its regional insecurities through US and European defense conglomerates under the guise of ‘deterrence’ and ‘integration.’” Qatar, meanwhile, is “constructing an expansive military infrastructure saturated with western hardware,” pointing to a strategy of more concealed normalization.

Cracks in the coalition

These tensions came to a head last month, following the Saudi crown prince’s meeting in Washington, ahead of which Trump pledged to sell 48 F-35 fighter jets to the Gulf nation. Within the Israeli government, the proposed sale sparked concern over the erosion of aeronautical superiority in the Middle East. Political and military leaders reportedly expressed frustration over US investment in a “hostile country without diplomatic relations,” arguing that maintaining the Zionist nation’s “qualitative military edge” remains essential to forming a coalition against Iran.

More recently, on Dec. 26, Saudi forces struck positions linked to the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC), exposing fractures within the Emirati-Saudi coalition that has carried out the war in Yemen for nearly a decade. Despite these tensions, Emirati officials continue to frame their involvement in Yemen as a commitment to stability and security, publicly reaffirming cooperation with Saudi Arabia even as their interests increasingly diverge.

The unraveling of alliances in Yemen’s protracted proxy war points to a broader shift in Emirati posture across the Gulf. The UAE is moving away from reliance on coalition consensus and toward the consolidation of an independent military capacity capable of contending with neighboring powers and managing conflict beyond its borders.

The logistics of mass atrocity

In Sudan, this defense coalition is tied to the logistical demands of the forces fighting over power. Abu Dhabi’s military and economic support for Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) likely shapes the logic of the Elbit deal. Since 2019, the UAE has supported the RSF, an armed militia who the USA, the UN, and several human rights groups have accused of committing numerous war crimes, including genocide.

In 2024, a New York Times report revealed the UAE’s construction of an air force base near the Sudanese border in Chad. In 2025, new Google satellite images show the base’s continued expansion. Abu Dhabi describes the site as a humanitarian hub, but observers allege that the UAE has used it to station Emirati drones and funnel illicit arms to the RSF.

The base’s development, which has unfolded alongside a widening drone arms race, cements the UAE’s belligerence in the Sudanese war. The Sudanese army has maintained air superiority by deploying a squadron of advanced Turkish drones supplied by the defense contractor Baykar, replacing earlier Iran-produced models.

According to The Washington Post, Sudanese army leaders offered access to natural resources, including copper, gold, and silver, to Turkish firms in exchange for expanded aerial capabilities.

For the RSF, which now faces a better-equipped Sudanese military, aerial defenses have become imperative for leader Mohammad Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti. Watchdogs have already traced a precedent for such systems entering Sudan through Emirati-linked routes. In April 2025, satellite imagery captured a FK-2000 truck-mounted antiaircraft system near Nyala Airport in South Darfur. Analysts later identified the system as Chinese-made, and determined that it had moved through the UAE and Chad before arriving in Sudan.

The fighting intensifies across Sudan this year, particularly in Darfur, where the RSF is committing a genocide. If the Elbit deal results in the development of RSF anti-missile capabilities, the UAE would deepen its involvement with one of the world’s most pressing humanitarian disasters in service of strategic interests on the African continent.

Two camps, one war economy

On Dec. 26, Israel became the first country to recognize Somaliland as an independent state and a signatory to the Abraham Accords. The move formalized a relationship that had already existed. The UAE established ties with the partially recognized territory in 2017, when it inaugurated a military base there, then appointed a diplomat to Hargeisa, Somaliland’s capital, in 2021.

The following day, Saudi Arabia moved in the opposite direction. On Dec. 27, Riyadh signed a joint statement affirming Somali sovereignty over Somaliland alongside several Arab foreign ministers. The UAE was notably absent from the signatories list, underscoring the growing divergence over the strategic value of normalization.

That divergence now extends beyond diplomacy and into war. Emirati leadership continues to support both the RSF and Somaliland to secure access to natural resources, consolidate influence in the Horn of Africa, and counter the Iranian and Turkish alliance backing the Sudanese army. At the same time, following a Dec. 19 meeting between American and Emirati officials, UAE Deputy PM Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan pledged support for US Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s efforts to secure a humanitarian ceasefire in Sudan, a signal of tactical accommodation with Washington rather than a reversal of Emirati strategy.

If Elbit’s J-MUSIC DIRCM system deploys on Emirati home soil, the technology would mark more than a defensive upgrade. It would signal a power shift on the Arabian Peninsula and reinforce the consolidation of an Emirati–Israeli security axis. Elizabeth Dent, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, argues that deepening Israeli–Emirati partnerships may support the Saudi Arabian and Qatari push to diversify their defense relationships in ways that more closely track American priorities.

These developments point to the emergence of two regional camps. On one side, UAE and Israel have increasingly pursued operational, technological, and territorial alignment; extending from the Gulf to the Horn of Africa. On the other, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf powers continue to anchor their military expansion in Western capitals, arms markets, and diplomatic cover, even as they avoid overt normalization with Israel.

This realignment bears costs. The US frustration has grown toward Israel, alongside renewed tensions with the UAE over its role in the wars in Yemen and Sudan. Yet Abu Dhabi appears prepared to absorb that friction. By expanding its military through Israeli technologies refined during the genocidal war on Gaza, the UAE seems to return its relationship with Israel to its pre-Oct. 7 footing , gradually distancing itself from the Saudi-led coalition forged during the war in Yemen.