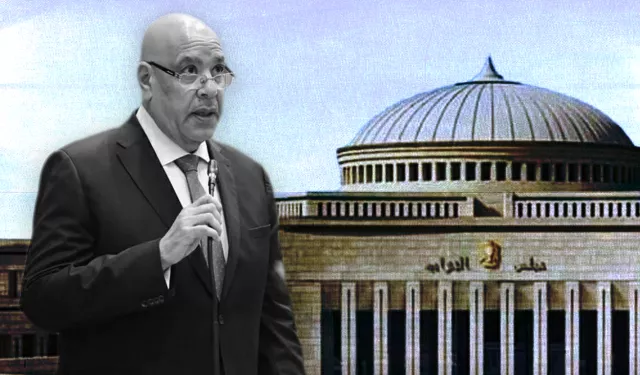

Hisham Badawi: From secret keeper to House speaker

In a scene that felt more ceremonial than contested, Hisham Badawi was named speaker of Egypt's House of Representatives, crowning a decades-long career defined by his proximity to power and his role as its silent custodian.

Badawi's name first gained wide recognition during his 12-year tenure as First Attorney General of the Supreme State Security Prosecution, from 2000 to 2012. According to official biographical sketches, he graduated from Cairo University's Faculty of Law in 1980 and joined the Public Prosecution in 1981 as an assistant prosecutor.

During his years at State Security, Badawi led investigations into high-profile cases such as the 2009 Hezbollah cell trial and other cases conversely tied to jihadist and takfiri groups. In a 2009 op-ed, the late Muslim Brotherhood leader Essam El-Erian recalled that Badawi had interrogated him over the course of some 20 sessions in 1995, describing the experience as “enjoyable…more than 100 hours of questions and answers.”

In that same piece, El-Erian addressed Badawi directly, reminding him of their “forced friendship” forged through interrogations and asking him to release a jailed and ailing Brotherhood figure.

Badawi's quiet revival

Badawi rose through the ranks of the State Security Prosecution under former Prosecutor General Abdel Meguid Mahmoud. But when Mahmoud was ousted in 2012 under a constitutional declaration issued by then-President Mohamed Morsi, Badawi quietly returned to the judiciary and slipped from the public eye.

Following Morsi's removal in 2013, Badawi resurfaced among a cadre of familiar judicial faces. Under Justice Minister Ahmed El-Zend, himself a former head of the Judges Club, Badawi was appointed assistant justice minister for anti-corruption. Between 2013 and 2016, he emerged as a key player in shaping Egypt's anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing policies.

This period saw substantial amendments to Egypt's 2002 anti-money laundering law, including the restructuring of its enforcement unit and expansion of its mandate to include counterterrorism. It also coincided with a surge in the activities of the Ministry of Justice's committees for seizing Muslim Brotherhood assets—a process that preceded the 2015 passage of the law regulating terrorist entities.

That law effectively transformed the act of asset seizure into an automatic consequence of a group or individual's designation as “terrorist,” replacing earlier administrative decisions with direct legal enforcement.

These moves followed a series of administrative court rulings that struck down the asset seizure committees' decisions, citing the constitutional guarantee of private property and the requirement that such seizures be ordered by a court of law.

The veil of silence

In 2015, Badawi was named deputy head of the Central Auditing Organization (CAO). Just a year later, in August 2016, he was promoted to its top post following the dismissal of its then-head, Hisham Genena.

Badawi's elevation to the position came in the wake of a political storm ignited by Genena's claim that corruption had cost the state over 600 billion Egyptian pounds (about $33 billion at the time) in 2015 alone. That controversy spurred the passage of legislation granting the president the authority to dismiss heads of oversight bodies—the same authority used to remove Genena in March 2016.

Genena's tenure from 2012 to 2016 had been marked by a notable uptick in the visibility of corruption reports and audit findings, as well as their coverage in local media, according to a 2019 report by the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression.

From the moment Badawi assumed the role, it became clear his mandate was to quiet the noise. The CAO's reports largely vanished from the public sphere. Discussions of financial misconduct and corruption in state institutions, once a mainstay in Genena's era, faded from headlines.

A former CAO official with the rank of assistant minister told Al Manassa that Badawi had “succeeded remarkably” in muting the agency. The blackout extended beyond the media, he said, noting that for years, the CAO's annual reports were not even submitted to the House of Representatives for public discussion—a departure from the practices of predecessors like Gawdat El-Malt, who had famously sparred with the government in parliament during Hosni Mubarak's final years.

The former official, who requested anonymity, drew a stark contrast between Badawi and El-Malt, describing the latter as a “historic leader” of the agency who had personally reviewed violations with CAO members and confronted government officials with their findings.

By contrast, the official suggested Badawi may have avoided presenting the reports due to “limited technical auditing expertise,” instead delegating such responsibilities to his aides. This, the source implied, may have contributed to his reluctance to engage parliamentarians directly.

Appointed back into the light

Badawi's appointment as speaker came despite strong competition from other high-profile legal and judicial figures, including former Supreme Judicial Council head Mohamed Eid Mahgoub, former State Council president Adel Azab, and constitutional law scholar Salah Fawzi.

Initial speculation favored Mahgoub, who was seen as the most prominent judicial figure in parliament. But a presidential decree appointing Badawi among 28 members of the chamber tipped the scales in his favor, paving the way for his elevation to speaker.

Now, as he moves from executive-aligned roles steeped in secrecy into the top post of Egypt's legislative body, a critical question remains: Can Hisham Badawi, long regarded as a loyal guardian of state secrets, transform into a voice for the people and a watchdog over government power?