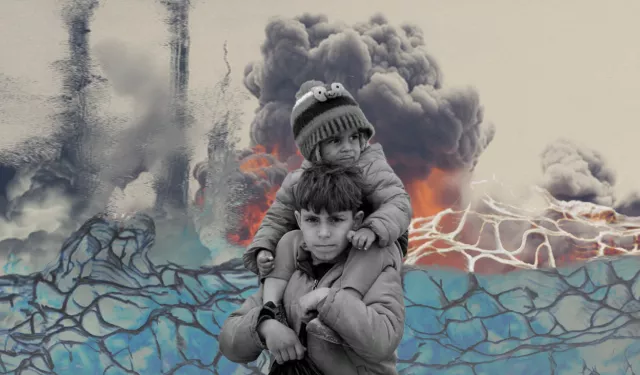

When sound breaks the bones of Gaza’s fragile patients

With every explosion in Gaza, Mohammed Al-Najjar faces the same question: how to protect his 14-year-old son, Hamed, not only from bomb shrapnel, but even from the thunderous sound of the blast itself and the tremors that follow.

Those vibrations could shatter the fragile bones of the teenager, who lives with osteogenesis imperfecta, a rare genetic condition also known as brittle bone disease. His suffering has been compounded by the humanitarian catastrophe imposed by Israel’s war on Gaza.

A month after Hamed was born, Mohammed, who lives with his family in the Qizan Al-Najjar area southeast of Khan Younis, learned that his son had the disease. It causes extreme bone fragility due to insufficient collagen production in the body.

According to Dr. Alaa Azmi, an orthopedic surgeon and spine deformities specialist at Al-Quds Hospital in the Tel Al-Hawa area of western Gaza City, people with osteogenesis imperfecta can suffer fractures from the simplest causes, “and sometimes for no clear reason at all,” he told Al Manassa.

Azmi added that the severity of the disease tends to decrease with age, with fractures becoming less frequent by adolescence.

However, reaching adulthood with fewer fractures requires preventive measures and proper healthcare. Maintaining bone strength and alignment during childhood is crucial—and extraordinarily difficult under Israel’s two-year war on Gaza.

Hospitals and so-called “safe” displacement shelters have been targeted, medicines have been blocked from entering the Strip, and fleeing bombardment has become a daily battle with pain.

Nightmares of displacement

Since he became aware of the world around him, Hamed remembers his father being “constantly committed to every instruction from the doctor.”

“I lived an almost normal life,” Hamed told Al Manassa. “But the war turned everything upside down. We started moving from place to place because we couldn’t stay anywhere that might put me in danger, especially if we had to flee suddenly.”

His father elaborated on the toll of displacement.

“Displacement has exhausted us financially and physically,” Mohammed said. “My son’s condition is very difficult. I’m afraid of any sudden movement. His bones break easily, and he can’t move quickly like other people.”

“For us, displacement is a nightmare. Every time the Israeli army orders an evacuation, we comply, and I’m terrified for him. I try to protect him in every possible way.”

Throughout the war, Mohammed also struggled to provide adequate food and essential medicines for his son, especially vitamins needed to strengthen his bones.

“I was terrified he would suffer a fracture,” he said. “If his thigh breaks, his entire leg has to be put in a cast from top to bottom to prevent another fracture. The cast is heavy, his bones are weak, and I was afraid every single moment.”

Although the war officially paused after the Sharm El-Sheikh agreement in October, Israeli authorities continue to block the entry of basic necessities. Nonessential goods such as nuts, soft drinks, tea, and coffee are allowed in, while medicines, meat, eggs, and fruit remain scarce, and are sold at several times their normal price when available.

Hamed remembers life before the war.

“A German delegation visited Gaza, and promised me a protective frame that would help me move and protect my bones,” he said. “But the war destroyed all my dreams. I’ve been deprived of playing since I was a child—and now I’m deprived of life itself.”

Fragile bodies facing sound and fire

Hamed is one of many Palestinians in Gaza whose brittle bodies have been pushed to their limits by war. One of them is Iman Abu Sabha, a Quran teacher who has lived with the disease for 39 years and relies on an electric wheelchair.

“My life was stable,” she said. “But the war pushed everything backward. There’s no suitable food, no medicine. My house was bombed, the roads are all rubble. Even getting to the bathroom has become a major problem.”

“I’m trapped at home. Even my wheelchair was destroyed when they stormed Khan Younis camp.”

The disease caused severe dwarfism in Iman’s case, meaning she requires a specially adapted bathroom and assistive equipment.

“With every evacuation order from the occupation army, I suffered physically and psychologically,” she said. “I need help with everything. My body is extremely sensitive, canned food weakens me, and there’s nowhere I can exercise.”

Iman has appealed to numerous institutions for help traveling outside Gaza to complete her treatment. She received a medical referral from the Ministry of Health at the start of the war with no expiration date, but travel priority depends on case severity—and she is still waiting.

“My leg has started to deteriorate, ulcers have appeared, and I get tremors throughout my body,” she told Al Manassa. “Vitamins are almost nonexistent. If I find them, they’re extremely expensive. It’s impossible to afford them during the war and widespread unemployment. And even after the war ended, nothing changed.”

Eight-year-old Amjad Sheikh El-Eid can no longer sit or live normally because of the same disease. Due to his young age, he is even more vulnerable than Hamed and Iman.

According to his father, Ahmed, Amjad’s bones broke even from nearby bombardments during the war.

“Sometimes he would fracture just from the sound,” Ahmed said. “The cast is heavy and causes fractures elsewhere, so we started using compression wraps and painkillers, and that’s a whole suffering in itself.”

Life before the war was very different, Ahmed told Al Manassa.

“From the day we learned our son had brittle bone disease, we monitored every movement and provided him with good food, supplements, and medication,” he said. “But after the war, everything disappeared, and if anything is available, it costs many times its original price.”

Where is the treatment?

There are no precise figures on the number of people with osteogenesis imperfecta in Gaza, but international estimates suggest one case in every 10,000 to 20,000 births.

Dr. Azmi said treating patients with brittle bone disease requires an integrated healthcare system—one that is unavailable amid the catastrophic conditions facing Gaza’s hospitals after the war.

“These patients are dying in silence,” he said. “Their names are not mentioned in the news. They die more than once every day, without anyone paying attention.”

He added that the hospitals still operating lack the most basic treatment requirements, including medicines, fixation materials and diagnostic tools, as well as prosthetics and physical therapy, all of which are essential for managing the disease.

“We are not talking about advanced treatment,” Azmi said. “We are talking about the bare minimum of care. There are no specialized medicines, no nutritional supplements, no protective equipment. Even casts are unavailable or applied in primitive ways that can worsen fractures instead of treating them.”

He warned that the sound of bombardment and forced displacement pose a direct threat to patients’ lives. A strong vibration or a wrong movement can cause multiple fractures, at a time when surgical intervention and medical follow-up are impossible.

“Patients with brittle bone disease need a calm, stable environment,” he said. “Instead, they are living in the most violent and unstable environment in the world.”

At night, Hamed returns to his temporary bed, carefully placing his cast-covered leg, and waits for another night of bombardment.

He does not dream of playing football or riding a bicycle—only of sleeping without something breaking inside his body.

In Gaza, people with fragile, glass-like bodies do not need miracles. They only need a life that hurts a little less.