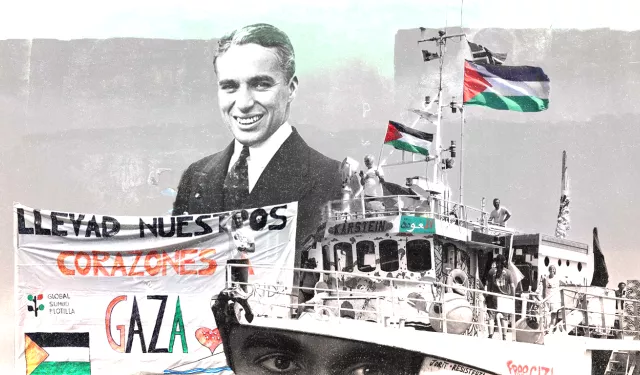

Sailing to Gaza, we wanted you with us Mr. Chaplin

A journalist holding a recorder roamed among the crowd at a recent solidarity rally for the Palestinian people in Madrid. She stopped in front of me with a single question: “What would you say to those who didn’t show up today?” I told her they should be out here with us. They need to be present. Yes, the Palestinian cause is first and foremost the cause of the Palestinian people—but it is also the cause of all the free people in the world. And at this moment, it matters more than ever. We must protect our lives, our shared world, from this new fascism—through every form of protest for Palestine.

She moved on, and left me thinking: I had just spoken in the voice of Charlie Chaplin. As if those words carried his spirit. Phrases not far from the ones that triggered state persecution against him in the US after “The Great Dictator” (1940), and his speeches against Nazism in the early 1940s. Those speeches that led the powers that be—and their obedient press—to hurl a familiar accusation: “Are you a communist, Mr. Chaplin?” He left the United States in bitter protest and never returned, as he recounts in “My Autobiography”.

Chaplin was not a communist. He said so repeatedly. But he sided—unapologetically—with justice, peace, and joy, as a citizen of the world. He never cowered in denial, never scrambled to clear his name. He calmly explained that although he did not adopt communist ideology, he saw the Soviets, who stood against the Nazis, as comrades. He used the word deliberately. They were protecting the democratic world from fascism’s dark tide. That was why he called on the United States to enter the war—to prevent Hitler from toppling the Soviet Union.

The forever-relevant Chaplin

Chaplin is one of those rare filmmakers to whom we return over and over again. From personal experience, I believe discovering him requires patience. His world unfolds in layers—each revisit bringing new meaning. As children, we laughed at the odd little man with the funny walk, who got into trouble, took pratfalls, and escaped through slapstick. We loved his impish grin. And we felt, perhaps naively, that the world, despite its cruelty, held a warmth and shelter—especially when he adopted a homeless child in “The Kid” (1921).

But Chaplin has more to offer. In youth—especially to those of us entering cinema—the laughter gives way to something deeper. Not because the comedy fades (it doesn’t), but because we begin to notice two things. First, the delicacy and human tenderness with which he builds his stories. How he weaves in fragments of his own painful childhood, using those wounds to create joy and intimacy on screen, forging emotional kinship between viewer and character.

Second, his mastery of cinematic composition. The sets, the props, the surrounding space—seemingly minor elements—acquire purpose as the scene progresses. They become essential, organically advancing the scene as a dramatic whole. Perhaps that’s Chaplin’s greatest instinct as a filmmaker: to shape the scene as a self-contained universe, a narrative cell, complete in itself—with everything needed for it to grow, unfold, and resolve.

This summer, I entered what I consider the third phase of Chaplin discovery. I returned to “the little tramp” amid the extermination of the Palestinian people in Gaza. I rewatched his films, reread his memoirs after more than two decades. But this time, it was no longer the childhood laughter, nor the student’s curiosity. It was the awakening to Chaplin the political philosopher. The dissident. The relentless critic of the powerful. The friend of the weak. The enemy of capitalism’s cruelty. The dreamer of a just and happy world.

This was Chaplin who made “Modern Times” (1936) as an indictment of industrial capitalism’s dehumanization. Chaplin who made “The Great Dictator” to warn us—if we don’t wake up, fascism will devour us all.

Chaplin in the time of genocide

At the end of “The Great Dictator,” a Jewish barber—disguised as the dictator—delivers a speech:

“Now let us fight to fulfill that promise! Let us fight to free the world—to do away with national barriers—to do away with greed, with hate and intolerance. Let us fight for a world of reason, a world where science and progress will lead to all men’s happiness.”

The film was a resounding success—and, like most of Chaplin’s work, it drew waves of anxiety and criticism. By then, he was already one of the most famous, successful, and wealthy filmmakers on the planet. Invitations followed—to speak at political conferences across the United States. Chaplin obliged. He took the stage and said exactly what he believed, without fear or compromise. For months he became politically involved, outspoken, relentless. The US joined the war. The war ended. Then the harassment began.

Chaplin reflected later on why he’d become so immersed, so outspoken—even more so than Orson Welles, with whom he had once shared the stage. There was a personal element, he admitted: the applause, the validation, the satisfaction of feeling like a global citizen. But there was something deeper: a visceral hatred of Nazism and racism. A sense of looming danger. And a moral imperative to act—no matter the cost.

This was part of Chaplin’s greatness—as artist and human being: the awareness that his films and fame were born of a worldview, a set of convictions, a vision for humanity’s future. A vision that led him into battles we remember today with longing. The kind of battles that make us whisper: We wish you were here, Mr. Chaplin—with your films, your courage, your moral clarity.

Chaplin understood that fascism is never satisfied. That it will try to consume the world. He warned against the illusion that any nation, however distant, could be immune. That same awareness is essential today as we confront the insatiable ambition of a settler-colonial state modeled on fascism. After Gaza comes all of Palestine. And the fantasy is no longer a strip of land in Lebanon or Syria—but the “spiritual mission” Netanyahu invokes in his vision of Greater Israel.

It is that same clarity we need now, as we face the killing machine and its allies among the global far right. A far right that once sent Jews to the gas chambers—and today embraces Netanyahu and cheers for Israel. Why? Because Israel is doing precisely what this far right dreams of: smashing politics, erasing democracy, and scrapping international norms born of WWII. They want genocide and ethnic cleansing to become legitimate tools—unpunished, unrestrained.

The far right knows: what Israel is doing in Gaza serves them. It drags the world backwards into barbarism. It offers a lesson to all peoples. It presents a model for tomorrow’s colonial order.

That’s why, today—on the docks of Barcelona, on Sunday, 31 August, as thousands gather to see us off as we board the boats of the Global Sumud Flotilla headed to Gaza—some may be thinking what I’m thinking.

We wanted you with us, Mr. Chaplin. We wanted your words to remind us all that marching in the streets or setting sail for Palestine is, in fact, an act of defending life. Defending children. Defending the future of humanity, wherever it may be.

This story is from special coverage file To Palestine| We sail, and your hearts sail with us

Sailing to Gaza, we wanted you with us Mr. Chaplin

As thousands gather to see us off at Barcelona’s docks, Chaplin’s spirit echoes. Marching or sailing for Palestine is defending life, children, humanity, and our future.

To Palestine| Messages from the sea

No one should have to travel from the western Mediterranean to the east just because the fascist state is committing genocide against the Palestinian people.

To Palestine| Paths of departure, routes of return

Yousef’s family fled Palestine on foot in 1948. Now, aboard the Global Sumud Flotilla, he attempts his first symbolic return, by sea, towards a homeland he’s never seen.

To Palestine| How can we recover from loving Tunisia?

From Sidi Bou Said to Gaza, Basel Ramsis writes of love, blood, and solidarity. On board the Sumud Flotilla, the journey resumes. Tunisia behind, Palestine ahead.

To Palestine| Fear, resistance, and a Catalana named Carol

It’s not my knowledge of the Arab-Israeli conflict, or of the Palestinian cause or even the latest news from Gaza that gives me a sense of purpose right now.

To Palestine| From boats of death to boats against death

The Senegalese migrant Serigne Mbayé Diouf joins the Global Sumud Flotilla, risking his life in a boat again, this time to stand with Palestinians in Gaza.

To Palestine| From Bahrain to Gaza carrying a father’s legacy

A Bahraini activist sails for Gaza, carrying his father’s legacy while passing it on to his sons, Salman and Salam.

To Palestine| Sailing through fear, carried by hope

As the Sumud Flotilla nears Gaza, Basel Ramsis writes of fear, resolve, and a global movement sailing not just toward Palestine—but against silence, siege, and surrender.

Published opinions reflect the views of its authors, not necessarily those of Al Manassa.