Property developers are the statelets ruling ‘Egypt’

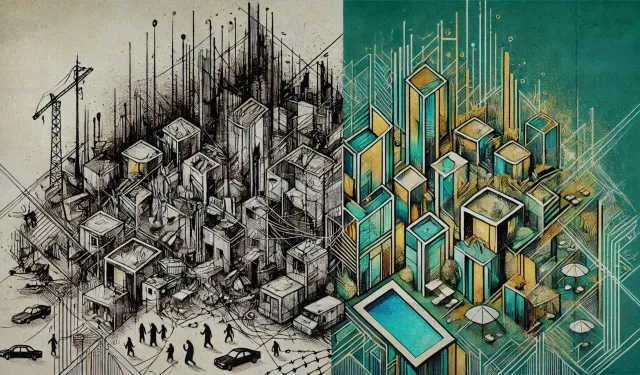

After 10 years of enforcing strict segregationist policies with blunt measures, class-based discrimination has now reached the level of official discourse. Egypt has become the only “republic” that openly divides its citizens into upper and lower classes, granting rights to some while denying them to others. The trajectory suggests that one day the constitutional ban on civil titles may be scrapped altogether, reviving the privileges of medieval lords and nobles, only to award them to a new class of “owners” among the “Egyptians”—while leaving the general public of “Masriyeen” (Arabic for Egyptians, singular Masri) to scavenge crumbs outside the walls of the new castles now called compounds.

In Egyptian colloquial usage, “Egypt” has come to function less as a neutral self-identifier and more as a satirical label for the privileged class. The term marks the elite as a westernized, insulated stratum, living behind gates, speaking a different idiom, and consuming global culture more than local life, a foreign body within the nation.

By contrast, the word “Masr” signals the authentic public, those who endure the state’s failures firsthand. This linguistic split, widely understood in everyday speech, captures the lived reality of separation between rulers and ruled, and is crucial to understanding the country’s deepening class antagonism.

Today, everyone has come to terms not only with the duality of “Masr” and “Egypt”—a split that has widened rapidly since 2014—but also with the strict demarcation between the two worlds, which prevents social mingling and reinforces the sense of privilege enjoyed by “clients” in “Egypt”.

This divide is deepened by the erosion of common public spaces where citizens of all classes once gathered as equals, such as public universities, parks, beaches, football pitches, festivals, and mass celebrations.

The quality of life in “Masr” is deteriorating. People are impoverished, their citizenship is stripped away, the law is repeatedly disregarded, chaos and filth prevail, and suffocating, treeless streets are choked with traffic. Privacy is disappearing, safety is diminishing, and the quality of education, healthcare, and public transportation services is declining.

This means that the most basic rights, which the state is supposed to guarantee, are transformed into class-based privileges. These privileges are sold by real estate developers at exorbitant prices, whose payment is not just in cash.

In this divided context, owning a house in “Egypt” is no longer a luxury for the wealthy seeking distinction. It has become the only way to secure a well-ventilated, sunlit home on a tree-lined street with sidewalks safe for walking—protected from prying eyes, criminals, and informants. Expensive private and international schools are no longer symbols of prestige but necessities amid the collapse of public education.

The age of public services is over; to access alternatives, one must live among the rich.

Thus, citizens’ basic rights in “Masr” have been commodified and are offered exclusively within the gated communities of “Egypt”. Real estate firms organize entry through a repulsive process of class-based social selection, gaining wide powers that have transformed them from market players seeking profits into emergent sovereign entities. They now impose collective adhesion contracts on their clients, monopolizing the very right to regulate life in their closed enclaves.

The company-statelet and sovereign powers

Real estate development and marketing companies, as well as other institutions offering services in “Egypt”, base their marketing and self-portrayal on being exclusive communities for the elite. They carefully select their clientele and offer a complete lifestyle, not just property or an educational or recreational service.

At first glance, the facts may seem to validate this claim. For instance, property prices in new developments are rising faster than in downtown Cairo, a gap that can be seen as a mechanism for class filtering or exclusion. That might be true, but, as economist Osama Diab argues, inflation obscures the fact that property values are in fact falling in real terms, despite price hikes.

Moreover, the very need for such class-based filtering mechanisms, such as price hikes or client interviews, or even architectural design, would not exist if real estate firms had not expanded their clientele beyond the entrenched elite to include the “suitable” segments of the middle class. Targeting the wealthy alone would not have required such elaborate filtering.

We can observe this in how the real estate sector ballooned from 13.1% of GDP in 2011 to 19% in 2022. Along with related industries and services, it became “the fastest-growing sector in recent years without rival,” according to economic analyst Amr Adly, who notes that most of this growth has been in luxury compound housing and related services.

In rare harmony, then, state institutions’ policies that render “Masr” unlivable align perfectly with the interests of these companies, which accumulate wealth by selling havens of calm, privacy, and security to those who have the means to flee the chaos.

Using the justification of protecting these havens from “riffraff” and asserting their right to choose whom to serve, these firms enforce systematic discrimination. They set classist social criteria for entry, impose binding decisions on residents, and condition access to purchased services on compliance.

For example, some firms interview potential buyers and exclude women who wear the hijab, holders of middling qualifications, or the children of divorced women—groups that many private schools also reject. In coastal resorts and leisure facilities, background checks may involve screening applicants’ social media accounts, at the expense of those who value privacy.

Thus, materially secure residents of “Masr” scramble to meet the firms’ conditions before their acceptance interviews, in scenes reminiscent of visa applicants at foreign embassies. Just as a visa grants entry and privileges, the company-statelet’s passcode grants access.

The authoritarianism does not end after purchase. Contracts examined by this writer show that some companies oblige buyers to use specific firms for interior finishing, or else deposit security payments until the workers they brought into the compound complete the job. Homeowners also surrender the right to alter their façades, even under rules agreed collectively by residents.

In their pursuit of lost citizenship rights, “Masriyeen” rush to “Egypt” seeking a minimum of decent living. Yet in this journey, they are compelled to surrender even the basics of citizenship, signing contracts that strip them of agency and allow private firms to usurp the state’s monopoly on binding decisions. The alternative is to remain in “Masr,” where most are officially treated as second-class citizens.

Managing class contact zones

In addition to granting visas for entry into their gated communities to outsiders and then monopolizing the organization of collective gatherings within these communities, the scope of sovereign acts exercised by these companies has expanded. This now includes the management of class contact zones where members of both worlds meet. These zones have become rare after the erosion of public gathering spaces, and are now almost limited to security and service provision, including finishing works, for which the companies hold the homeowners hostage in the adhesion contracts they impose on them.

The rationale behind requiring deposits when owners hire external workers is that no “Masri” can exist in “Egypt” without a sponsor. All “Masriyeen” there are employees or laborers accountable to a firm that regulates their presence and behavior. It is therefore deemed normal that residents bear financial liability if they import their own workers. “Masriyeen” are suspect by default in “Egypt” and unwelcome as individuals.

By monopolizing these scarce class contact zones, developers deepen segregation and keep it under surveillance. And just as they lied when claiming to build exclusive elite communities, they also lie in claiming to build safe and sustainable ones. In reality, such arrangements produce fragile societies.

On one hand, companies lack the permanence of states, remaining at the mercy of volatile markets. On the other hand, no entity can indefinitely control every point of class contact.

Historically, political power monopolized Egyptians’ right to self-organization and abused it in their name. Laws were passed by parliaments elected in rigged votes, and policies were set by governments that never truly represented citizens. Yet all this was at least nominally in the name of the people, with some regard for balancing interests.

In the “New Republic,” however, the rules of life for first-class citizens are drafted in company offices, enforced by contracts that acquire binding force by the very divisiveness of society. These arrangements may be the least bad option for individuals, but they can never be sustainable. For sustainability requires that the millions left outside the walls secure at least a minimum of their interests—without having to beg for entry.

A version of this article first appeared in Arabic on Dec. 1, 2024

Published opinions reflect the views of its authors, not necessarily those of Al Manassa.