Gen Z & the Revolution| Lessons from the road to Palestine

The revolution erupted when I was standing on the edge of adolescence. I was 12. Its public mood seeped into my body before it reached my language. Through it, I learned anger, confusion, and the urge to reject and resist. In the street, I found something that looked like me. My inner rebellion found its mirror there, and the two became part of the same experience.

In our home, political discussion was part of everyday life. My mother complained of her distance from her family, the soaring cost of living, the regime’s looting of the country’s resources and the systematic impoverishment of its people. My father complained about traffic congestion, the absence of public spaces and the ubiquity of bribes.

I remember their hostility toward the regime, especially its prisons, and the terror its police inflicted on the people, often likened to the practices of the Zionist entity. Yet all of this was said cautiously, always followed by the same warning: “Don’t repeat what’s said here outside the house.”

My first relationship with politics came through my mother. She is Palestinian, living in exile in Egypt, cut off from her land and her family. Palestine was part of my formation, a context we lived within, not an abstract idea up for debate. My grandfather could not visit us, because the Egyptian state did not recognize the Palestinian refugee document he carried from Lebanon.

As a child, I struggled to grasp this reality. How could a state prevent a daughter from seeing her father, or a child from seeing her grandfather? I did not understand the laws, but I saw their impact in my mother’s grief and anger. Those feelings reached me through her, without explanation. The one emotion my mother refused was defeat. She insisted on holding fast to the cause and believed in the Palestinians' right to return, no matter how long it took. She made sure I knew my history and understood what belonging and resistance meant.

She taught me that the struggle for return is an ongoing process of resistance, the very essence of liberation. From this understanding came the lesson of boycott. We boycotted American companies because they were complicit in the killing of our people in Palestine and in their displacement from their land. She taught me about our village, Alma, near Safad, and had me memorize the story of her grandfather, who insisted on staying until he was forced out at gunpoint.

Accumulating anger

When we visited our relatives in southern Lebanon, they would take us to the border village of Bint Jbeil so we could see Palestine and recognize the shape of our land, even from afar. The moment my eyes met the land, my political compass was set. Between my mother’s insistence on raising my political awareness and her fear for me, she constantly reminded me that words have a price. She warned me against sharing any political talk outside the house, “so we don’t end up in prison.”

My school was in Tora, south of Cairo, where the notorious prison loomed in my daily view. On my way to school, it reminded me that the state was watching, and that speech carried consequences. I did not fully understand my inner turmoil, the feeling that I was hiding who I was; that I despised this regime. I was afraid anyone might discover the depth of that hatred. I saw the regime as the reason my father was absent for long hours, working to provide us with a dignified life under mounting financial pressure, and the reason for my mother’s misery, separated from her family.

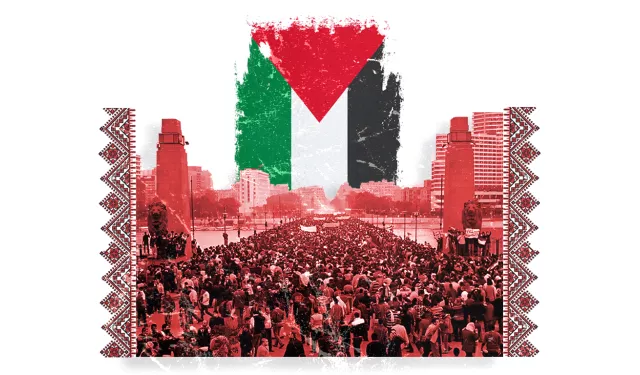

That anger exploded with the revolution, which shattered barriers and left me stunned. The streets filled with chants, and the collective body became visible. I still remember my mother’s cry: “The people have woken up!” She celebrated as if she had been waiting her whole life for that moment.

For the first time, I felt that the misery dominating our home could actually lift. I watched people’s courage as they poured into the streets, with admiration tempered by fear. The question of fate was always present: Would the regime let them return home, or would prison be their end?

The contagion of courage reached my mother, too. She was no longer afraid. She urged my father to join the protesters. We went down to the streets, and in those first days she insisted on taking me and my siblings to the square. Our presence was symbolic, but she wanted to anchor the reality in our consciousness: This revolution belonged to us, and its outcome would shape our future.

In the first march I joined, my voice rose from my chest without calculation for the first time, becoming part of a larger sound. It was an extraordinary feeling to emerge from the isolation of anger into collective participation. Everything suddenly felt possible. We would reunite with my grandfather and my mother’s family! We would liberate Palestine! We would no longer struggle financially! We would no longer fear prisons!

That energy spilled into my school and into my dreams of change. The school was a miniature mirror of the state. We were a middle-income family. My father was a civil servant, my mother a teacher, and education was the highest value in our home. Yet the school was designed on a starkly class-based system: favoritism based on parents’ positions, deliberate neglect of the National-track classrooms in favor of the International sections, and daily bullying met with silence.

An incomplete revolution

After the revolution, and everything it taught me about struggle and defiance, silence became impossible. Along with a group of students, I organized a complaint, with quiet support from a few teachers. The response was swift and decisive. I was barred from one exam, and the principal openly threatened me, saying she would not allow a child to “challenge” her. What happened was not shocking so much as it was revealing. The revolution had not toppled the system, but it had exposed its mechanisms.

I was angry, but the deeper anger came with the victory of the counterrevolution.

The transition into that era was fraught with conflict. My family stood with the revolutionaries, and there was a price to pay. Bitter disputes erupted with relatives. With the first presidential election, a sense of defeat seeped from my parents into me. The choice between Mohamed Morsi and Ahmed Shafik was jarring. How could a popular revolution end up here? How could everything that had happened be reduced to two options that represented none of the revolution’s demands?

I remember the heated debates at school, as our class split between supporters of Morsi and Shafik. I burned with anger, unable to accept this reality. I could not understand the absence of alternatives. It was clear that both candidates were aligned with their own political interests. This political dead end deeply demoralized my family. The question shifted from how to realize the revolution’s demands to a more bitter one: Was boycott now the only option? The horizon narrowed, and authoritarian systems simply changed faces.

My political consciousness was still forming. I lacked the tools to fully grasp the moment and its complexities, but I felt its weight. The confusion of that phase became part of my makeup, as “revolution” collided with the limits of “reality.” My questions about power and alternatives sharpened. My frustration deepened when the counterrevolution restored the language of caution and fear of prisons to our home.

I was stunned. How could we abandon the square that had once seemed the only path to our freedom, and to Palestine’s freedom? How did we so quickly return to “keep your head down”? I struggled to understand how the revolution ended in such pervasive fear, and how we were asked to return to silence after barriers had been broken and a horizon opened that seemed impossible to close.

Anger settled in me when I saw the square emptied of its revolutionaries.

Alongside the anger came grief for the martyrs, and a heavy sense that we were unworthy of their sacrifices. Over time, those feelings turned into withdrawal. I stepped away from politics, as if even looking at Cairo had become painful. I mourned Palestine, and my mother, who returned to her old despair. I lost faith in the idea that “the road to Al-Quds runs through Cairo,” and felt that the city had betrayed that road when it abandoned the square, abandoning itself and others at the same moment.

The revolution ended, and like many of my generation, I found myself in exile. I traveled to Canada to study and work. Exile was an attempt at survival: a minimum of financial stability, and distance from prisons. But I quickly discovered that the West I fled to was a pillar of the same repressive system I had escaped. I learned that Canadian police had sent officers to train Egyptian police in 2015. I watched them practice the same repression here: violently dispersing demonstrations and arresting protesters, especially Indigenous people, Palestinians and their supporters, who are often labeled terrorists. The rhetoric and justifications were no different from those used in Egypt.

This realization reshaped how I saw the revolution and my role within it. January was defeated because it confronted a global capitalist system that profits from repression and continually reproduces it.

The counterrevolution is the product of a systematic global structure. Exploitation, racism, security policies and selective human rights discourse revealed to me the contours of a transnational imperial capitalist order, one that reproduces violence and injustice from West to East in the service of a ruling class that transcends borders.

I saw how Canada claims adherence to international law while killing its indigenous people and financing genocide in Sudan and Palestine. How politicians speak of faith in human rights and social cohesion while police target minorities, and governments slash health, education and public services to double down on police and military budgets.

For this reason, I returned to January in my early 20s as an open question and an extended struggle whose course has not yet been completed. I began studying it again as the outcome of a global structure and an unequal moment of confrontation. With every reading, it became clearer that Egypt’s central position in the struggle to liberate Palestine is a constant truth, beyond the ebb and flow of revolutionary waves.

Every path to Palestinian liberation runs through Cairo. My anger at Cairo shifted into an awareness of my role within this long struggle, one that continually reshapes itself and, in doing so, reshapes my responsibilities toward it.

In contrast, the counterrevolution seeks to imprison the revolution within a tragic frame: a finished past, a missed moment, one for which anyone who believed in it must be disciplined. In this context, the authorities invested heavily in expanding prisons and deepening their presence, until they became tools for policing imagination before geography. Their proliferation is painful, because it signals the persistence of efforts to block any vision of a different future.

The names of detainees pile up, and their absence becomes a heavy question about the meaning of struggle in a reality where imprisonment is no longer confined to politics but extends to everything: speech, art, writing and imagination itself.

Today, I see January with less romance and less cruelty. I see it as an experience that laid bare the limits of the world and the limits of organization at this moment, the limits of what can be achieved simultaneously. The generation of the revolution paid the first price with their bodies, their years and their freedom. We are living the continuation of a struggle that did not begin in January, and will not end with it.

And I, who began this story as a child awed by voice and collective action, now find myself a student of this revolution. I learn from its courage, its mistakes and its limits. I learn so that I can be ready, not to repeat the moment, but to imagine a new revolutionary reality and to build what comes after.

This story is from special coverage file Gen Z & the Revolution| Speak, and be seen

Gen Z & the Revolution| It is time for the January generation to step aside

If we possess a theory or a lesson from January’s lost lessons, perhaps we can direct the raging flood toward those who deserve it, without devouring everything in our path.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Realism, after the rush

One of the most important effects of the January Revolution on my generation is that it shaped a restrained, cautious political awareness. We do not trust revolutionary rhetoric

Gen Z & the Revolution| The children of open wounds

A personal reflection on growing up in the aftermath of Egypt’s revolution. Inherited defeat, enforced silence, and a wound passed down to a generation too young to choose it.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Egypt's last supper

Was the revolution assassinated or did it succumb to its own internal friction? A dive into the generation gap, historical falsification, and the struggle for a new narrative.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Raised by the elephant in the room

Raised in the shadow of January 25, I learned politics through fragments: photographs, fear, and unanswered questions about what happens after victory.

Gen Z & the Revolution| The flood on the horizon

The January revolution’s “failure” wasn’t preordained, but it was certainly shaped by a limited, if understandable, political imagination.

Gen Z & the Revolution| A generation taken off the will

Can a revolution that isn't passed down still be called a revolution? Seif El-Din Ahmed reproaches the "wounded" generation for locking the door to history on their children.

Gen Z & the Revolution| The nettles swaddled between the revolution’s leaves

I was 10 when Tahrir lit up my world with heroes. Now, at the square's sanitized corpse, I'm just a fragment of their failed dream—watching my generation turn nettles into memes.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Not all battles were public

Too young for politics, but too old for innocence: Wafaa Khairy reflects on growing up in Upper Egypt and why the "real" revolution must start in the home, not just the street.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Lessons from the road to Palestine

My first relationship with politics passed through my mother’s body. She is Palestinian, living in exile in Egypt, cut off from her land and her family.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Reckoning with the rot

Growing up in the womb of the counterrevolution, I watched the burial of January. But revolutions don't succeed overnight; they pave the way for a longer experiment.

Published opinions reflect the views of its authors, not necessarily those of Al Manassa.