Gen Z & the Revolution| The nettles swaddled between the revolution’s leaves

The traffic bottleneck at Tahrir gives me time to take in what remains of it every time I pass by.

The towering obelisk and the four ram-headed sphinxes surrounding it were uprooted from Luxor and placed at the heart of the square in what Reuters once called a “facelift” of the revolution’s epicenter.

Every time I pass through, I feel estranged from the square etched into the folds of my memory, though I only saw it in real life for the first time at fifteen, when we finally moved to Cairo.

As I leave the congestion behind, the square’s manufactured stillness dissolves, and its older image asserts itself again: a sea of people marching, opposing treacherous bullets with their bodies bathed in the halo of the tangerine orange glow that once brought the square to life at night, offering a certain warmth the sun cannot provide.

I remain outside the frame of that image, a spectator to a moment I could never step into.

That is the condition of a generation that came of age in post-revolution Egypt; perpetual passengers in a history we didn't get to inhabit.

The awakening

I was ten when the revolution broke out. Having lived in Hurghada, a coastal Red Sea city far away from the revolting capital, the TV was on twenty-four seven, even as we slept because the square never did.

I resorted to the internet to try to make sense of the conversations that dominated every adult gathering talking felul, ahzab, betrayals, and dreams. Unattended access to the revolution’s digital nerve center gave me details and footage I probably should never have seen at that age.

And yet, as it manifested before my eyes, the revolution was my first clear encounter with the dichotomy of evil versus good.

I couldn’t have explained the economic grievances or the political theory, but I knew, with a child’s unshakable certainty, that the people in the square were heroes. My heroes.

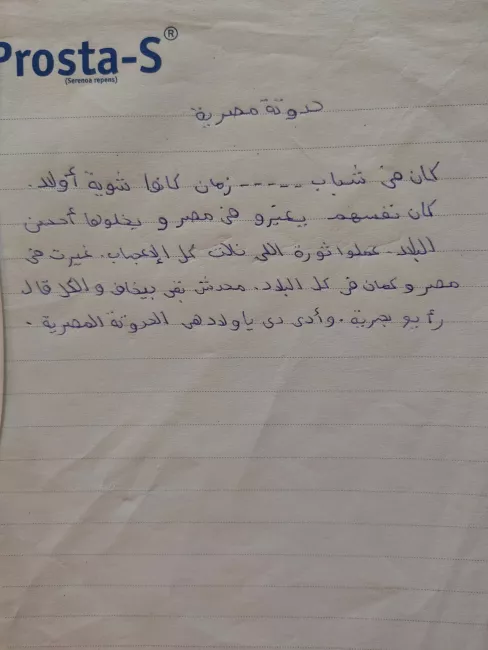

They had promised a better homeland, and with the simple faith of a ten-year-old, I believed them. And because I believed, I picked up a pen and wrote in my mother tongue for the first time:

Once upon a time, some youths—boys not long ago

Dreamt of changing Egypt, of crowning it among the lands

They orchestrated a revolution that set the status quo,

Changing Egypt and worldwide stands

Fear was no more, and the freedom to express finally prevailed

And this, children, is the Egyptian tale

In the direct aftermath, I stood on a small stage in our town at a gathering of people from all walks of life. I recited my love poem to the revolution and its people—a collectiveness that felt, for that moment, like it included everyone.

Until it didn’t.

The grand escape

Riding such a high wave ultimately meant the fall would be shattering. I am in no business of defining the politico-economic aftermath—yet as I grew into adolescence, I experienced the social dissolution firsthand. It was not in laws or headlines, but in the living room.

The gatherings that once vibrated with furious, hopeful debate grew quiet. The same groups that had once glued themselves to the TV now changed the channel when the news came on.

Whenever I tried to make sense of the change, I was met with a pat on the head. “What would YOU know,” became the refrain. “You just had to be there,” was the ultimate dismissal, transforming my first ever awakening into an exclusive experience I was forever too young to join.

It was also my first time hearing “you” instead of “we.”

Their generation quietly retreated—some by choice, others by force—abandoning the sinking ship without teaching us the safety instructions, leaving us to navigate the rising water alone.

The “third places” for dreaming together, from virtual forums to physical clubs, vanished, replaced by the isolated glow of individual phone screens.

What remained of the conversation ossified into an annual lament. Every January, a ritual of recycled op-eds, competing claims over who “owned” the revolution’s legacy, a new academic deconstruction of its failures. It became a fight over a corpse.

And from my relegated corner, year after year, I watched this spectacle of ownership. Anger curdled inside me—not at the reminiscence, but at its stubborn refusal to look forward, to ever ask: What has this quest done for the generation that followed? What have we left for them?

Instead, we became a punchline about being clueless, politically naive, dissociated. In their meticulous, multifaceted narratives that dissected gender, class, and ideology, they carelessly dropped our existence.

We became the sub-narrative; the nettles swaddled between the revolution’s leaves.

What now?

We were left undeveloped. A generation suspended mid-air, then dropped. Without a solid social idea to land on, we dispersed.

What grew was not another collective, but its digital afterlife. Our "we" exists in the archipelago of the internet—in the alchemy of turning shared trauma into a viral meme, in the solidarity bound to black squares and hashtags.

We became individualists, yes. But not in a philosophical sense—in the sense of survival. We optimize private escape routes because the project of building a shared home never laid a foundation stone.

So, did the revolution fail? To us, that is the wrong question.

To us, the revolution fragmented, and we are its fragments.

Yes, we may be dispersed—sharp, living pieces of the whole that once was. But the nettles are not the story. They are the evidence that a story was here; a byproduct of neglect, an attempt at survival.

Even in neglect, something continues to grow— stubbornly, alone, together.

Yet, the question remains: Can nettles, left to grow on their own, eventually learn to bloom?

This story is from special coverage file Gen Z & the Revolution| Speak, and be seen

Gen Z & the Revolution| It is time for the January generation to step aside

If we possess a theory or a lesson from January’s lost lessons, perhaps we can direct the raging flood toward those who deserve it, without devouring everything in our path.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Realism, after the rush

One of the most important effects of the January Revolution on my generation is that it shaped a restrained, cautious political awareness. We do not trust revolutionary rhetoric

Gen Z & the Revolution| The children of open wounds

A personal reflection on growing up in the aftermath of Egypt’s revolution. Inherited defeat, enforced silence, and a wound passed down to a generation too young to choose it.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Egypt's last supper

Was the revolution assassinated or did it succumb to its own internal friction? A dive into the generation gap, historical falsification, and the struggle for a new narrative.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Raised by the elephant in the room

Raised in the shadow of January 25, I learned politics through fragments: photographs, fear, and unanswered questions about what happens after victory.

Gen Z & the Revolution| The flood on the horizon

The January revolution’s “failure” wasn’t preordained, but it was certainly shaped by a limited, if understandable, political imagination.

Gen Z & the Revolution| A generation taken off the will

Can a revolution that isn't passed down still be called a revolution? Seif El-Din Ahmed reproaches the "wounded" generation for locking the door to history on their children.

Gen Z & the Revolution| The nettles swaddled between the revolution’s leaves

I was 10 when Tahrir lit up my world with heroes. Now, at the square's sanitized corpse, I'm just a fragment of their failed dream—watching my generation turn nettles into memes.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Not all battles were public

Too young for politics, but too old for innocence: Wafaa Khairy reflects on growing up in Upper Egypt and why the "real" revolution must start in the home, not just the street.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Lessons from the road to Palestine

My first relationship with politics passed through my mother’s body. She is Palestinian, living in exile in Egypt, cut off from her land and her family.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Reckoning with the rot

Growing up in the womb of the counterrevolution, I watched the burial of January. But revolutions don't succeed overnight; they pave the way for a longer experiment.

Gen Z & the Revolution| Why I chose the state

Why do I support the current regime’s stance toward January? Because I prefer a half-state to no state at all. I prefer a clear, even difficult trajectory.

Gen Z & the Revolution| American echoes, Egyptian wails

We live in the same shack of repression, sparring like roosters and celebrating hollow victories. Hatred is a luxury we cannot afford when everyone’s life is precarious.

Published opinions reflect the views of its authors, not necessarily those of Al Manassa.